Chukas: A Maimonidean Explanation for Parah Adumah (from a Different Moshe)

Yes, even the red heifer has a reason. Rambam paves the way but stops short of delivering. Another Moshe offers a theory that might make Rambam say, "Eureka!"

This week’s Torah content is sponsored by Naomi and Rabbi Judah Dardik, with gratitude to those who teach, lead, and strengthen Klal Yisrael, and with special appreciation for Rabbi Moskowitz zt"l.

Click here for a printer-friendly version of this article.

Chukas: A Maimonidean Explanation for Parah Adumah (from a Different Moshe)

Rambam’s “Go To” Taam (Rationale) for Chukim

Rambam’s theory of korbanos (sacrifices) might best be described as “infamous.” He essentially maintains that Hashem “preserved” korbanos as a vestigial relic of the dominant forms of idolatrous worship that prevailed in the ancient world, as a concession to human nature, which couldn’t abandon those practices all at once. By redirecting those rituals toward Hashem and restricting their scope, the Torah aimed to gradually uproot avodah zarah and guide the nation toward the true form of Divine service: knowledge and contemplation of God. (See Moreh ha'Nevuchim 3:32.)

Many of the taamei ha’mitzvos (reasons for the commandments) provided by the Rambam in the Moreh follow this approach, including the prohibitions of basar b’chalav (meat and milk), shaatnez (wool and linen), begged ish/ishah (crossdressing), pe’as ha’rosh ve’ha’zakan (rounding the corners of the head and beard), and others.

In fact, Rambam goes so far as to say (Moreh 3:49) that if there’s ever a mitzvah whose rationale escapes us, it’s likely aimed at uprooting a belief or practice of avodah zarah (idolatry):

In the case of most of the chukim (statutes) whose reasons are hidden, their sole purpose is to distance us from avodah zarah. As for those specific details whose reasons are hidden from me and whose utility I do not understand, this is because things heard are not like things seen. Accordingly, my knowledge of the practices of the Sabians (ancient idolators), which comes from books, is not like that of one who witnessed their deeds firsthand, especially since those beliefs have disappeared two thousand years ago or more.

If we knew the particulars of those practices and heard detailed accounts of those beliefs, the modes of wisdom underlying the specifics of the korbanos, the laws of tumah (halachic impurity), and other such matters—whose rationale, to my mind, has not crystallized—would become clear to us. For I have no doubt that all of this serves only to erase those mistaken beliefs from the mind and to abolish those useless practices by which human lives were consumed in vanity and futility …

Now, as we have explained, most of the mitzvos exist only to uproot those beliefs and to ease the immense, exhausting burden, the toil, and the anguish that those nations had established in their worship. Therefore, any Torah command or prohibition whose reason is hidden from you is nothing but a remedy for one of those illnesses, which—thank God—we no longer recognize today. This is what ought to be in the mind of anyone possessed of perfection, who knows the truth of His statement, exalted be He: “I did not say to the seed of Yaakov, ‘Seek Me in vain’” (Yeshayahu 45:19).

To sum up Rambam’s rule of thumb: when in doubt as to the reason for a chok, assume it was commanded to uproot some belief or practice of avodah zarah. If we had full knowledge of ancient idolatry, we’d understand the rationale behind all the chukim, including korbanos and the laws of tumah.

Rambam’s Explanation of Parah Adumah (or Lack Thereof)

One might expect Rambam to apply his signature approach to the parah adumah (red heifer). Yet in his treatment of mitzvos related to taharah (purification) in Moreh 3:47, he mentions parah adumah three times but never offers a full explanation. The first mention is brief:

The more prevalent a form of tumah is, the more difficult and delayed its purification will be. Tumah from being under the same roof as a corpse—especially that of a relative or neighbor—is the most common of all. There is no taharah from it except through the ashes of the parah adumah, rare as they may be, and only after seven days …

The second mention is even briefer:

Corpse impurity is purged only after seven days and only if the ashes of a parah adumah are found.

Still, no real explanation. The third reference occurs in the context of taharas ha’metzora (purification of a person afflicted with a divinely ordained skin affliction):

The midrashim do offer explanations for why purification involves cedar, hyssop, scarlet wool, and two birds, but that is not relevant to our present discussion. As for me, I have not yet discerned a single reason for any of these elements, nor do I know the rationale for the use of cedar, hyssop, and scarlet wool in the parah adumah, or for the hyssop branch used to sprinkle the blood of the korban Pesach (Paschal Lamb). I have found no firm basis for why specifically these species were chosen.

This is followed by the closest thing he offers to a taam ha’mitzvah:

The parah adumah is called a chatas (“sin offering” or, literally, “purgation offering”) because it completes the purification of someone who became tamei (halachically impure) from contact with the dead, enabling that person to reenter the Mikdash. For from the moment one becomes tamei through contact with a corpse, one is permanently barred from entering the Mikdash or eating kodashim (consecrated food), were it not for this cow, which “bore” that defilement—like the tzitz (the priestly frontlet), which atones for impurity, or like the goats that are burned. Accordingly, one who handles the parah or those burnt goats renders his garments tamei, just as the se’ir ha’mishtaleiach (the scapegoat), which is believed to bear many sins, imparts impurity to anyone who touches it. So from this category we have explained what we do know of its rationale, as it appears to us.

Perhaps Rambam expects us to read between the lines and extrapolate a theory from the clues he provides. Perhaps he had a theory but chose not to divulge it. Or perhaps he really didn’t know.

Thankfully, R’ Moshe ben Yitzchak Ashkenazi (1821-1898, also known as R’ Moisè Tedeschi) picks up the baton, offering a compelling Maimonidean explanation of the parah adumah in his commentary, Ho’il Moshe.

Ho’il Moshe’s Maimonidean Explanation

Ho’il Moshe (Bamidbar 19:2) opens with a striking reflection on the fine line Moshe Rabbeinu had to walk in leading the Israelites out of Egypt, balancing the Torah’s opposition to idolatry with the reality on the ground:

In the first generation after leaving Egypt, the Israelites were not yet strong in their belief in Hashem’s Oneness, and we see them bringing offerings to goat-demons, the deities of the wilderness. Therefore, Moshe did not speak with open mockery and derision about these deities, as David, Yeshayahu, and Yirmiyahu [later] did. He even referred to them as elohim acherim (other gods) as though they had substance, to avoid directly contradicting the prevailing mindset of the generation. Doing so would not only fail to establish belief in [Hashem’s] Oneness in their hearts, but it would have further alienated them from it … Nevertheless, Hashem commanded Moshe numerous mitzvos and chukim (statutes) that ran counter to the practices of Egypt and the other nations among whom Israel dwelled. This is the rationale behind many of the chukim: hidden from us but known to Moshe’s generation.

Although Rambam, to my knowledge, doesn’t explicitly state that Moshe Rabbeinu softened his rhetoric to avoid provoking resistance, it stands to reason he’d be open to the idea, seeing as how it follows the same line of thinking as his theory of korbanos.

Having laid that groundwork, Ho’il Moshe offers his explanation of the parah adumah:

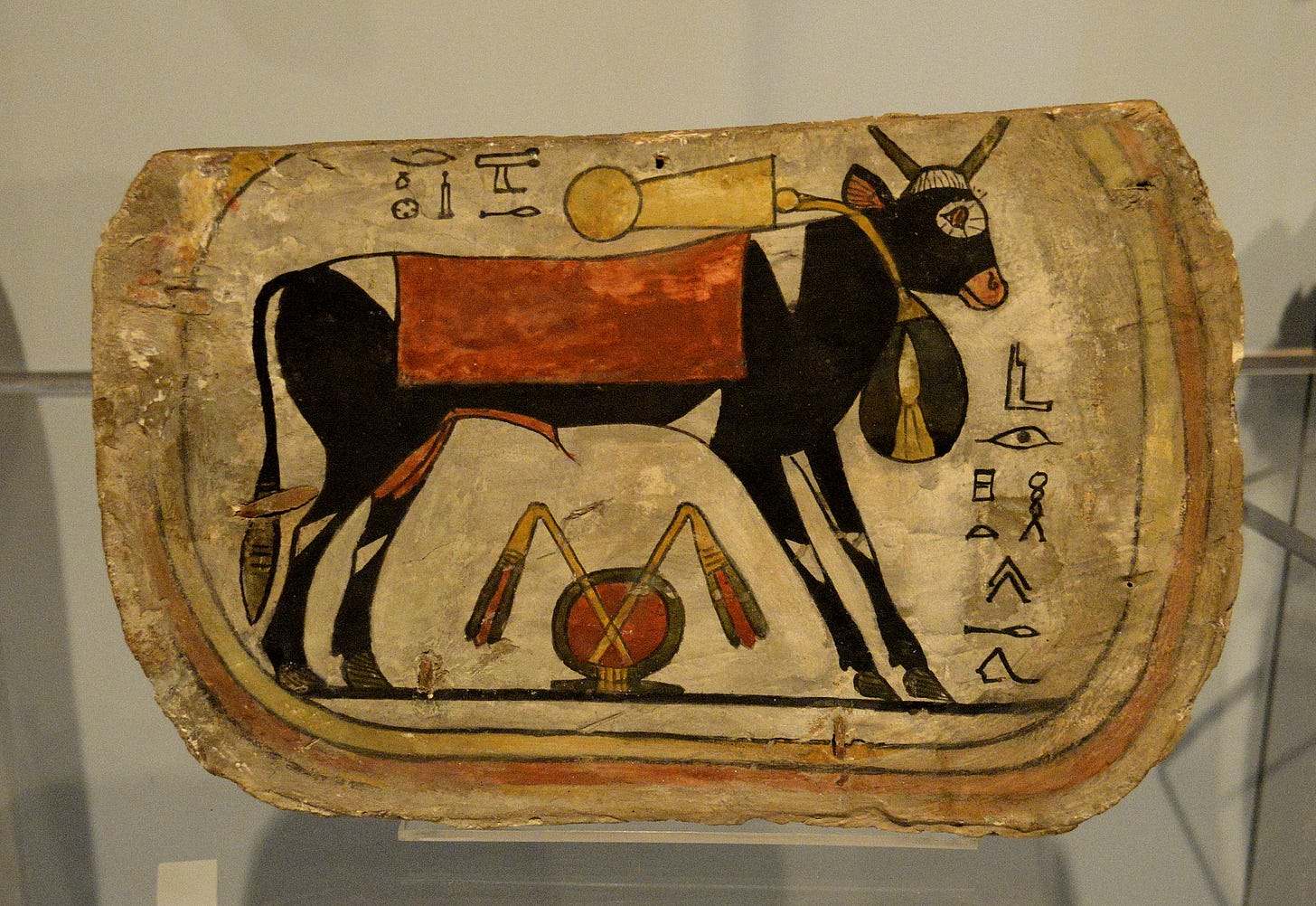

In Egypt, they worshipped an ox that was entirely black with a triangular white mark on its forehead, or the opposite: a white ox with a black mark. Hashem commanded Moshe to take a cow instead of an ox, one entirely red (neither black nor white), and to have it burned, so that its ashes would remove impurity, for ashes remove filth and stains. Yet the one who handles them does not become kadosh (sanctified) but rather becomes tamei.

In other words, the parah adumah was a polemic against a specific Egyptian ritual. If Ha’Kadosh Baruch Hu hadn’t provided a “substitute” for that practice—or if He had directly opposed it—the Israelites would have rejected it. Like all korbanos, the parah adumah is a concession to human nature: a bedieved (less-than-ideal), mitigated form of an idolatrous ritual, reformatted and redirected toward Hashem.

Evidence from Egyptology: The Apis Bull

When I first read this, I thought to myself, “Interesting! Kinda bold of him to go out on a limb by providing specific features of the Egyptian practice that the parah adumah was intended to polemicize against!” After all, he could have just sketched an approach but admitted we don’t know enough to say for sure—like Rambam does in his explanation of basar b’chalav in Moreh 3:48:

As for the prohibition against eating basar b’chalav, it is in my opinion not improbable that … avodah zarah had something to do with it … this is the most probable view regarding the reason for this prohibition, but I have not seen this set down in any of the books of the Sabians that I have read.

But then I did a quick Google search and discovered that there was a practice exactly like Ho’il Moshe described: the Apis Bull. Here are some excerpts from WorldHistory.org, curated to provide an overview:

Apis was the most important and highly regarded bull deity of ancient Egypt … Each individual deity had their own sphere of influence and power, but Apis represented eternity itself and the harmonious balance of the universe …

In the Early Dynastic Period, the ritual known as The Running of Apis was performed to fertilize the earth … The bull was selected, after a careful search, based upon its appearance: it had to be black with a white triangular marking on its forehead, another white marking on its back in the shape of a hawk's or vulture's wings, a white crescent on its side, a separation of the hairs at the end of its tail, (known as the "double hairs") and a lump under its tongue in the shape of a scarab. If a bull were found with all of these characteristics, it was instantly recognized as Apis, of course, but even a few or one would suffice …

After a period of 25 years, if the bull suffered no disease or accident, it was ceremonially killed … A state of mourning was decreed during which the bull's body was mummified with the same care given a king or noble, and at this same time, priests were sent out to find a replacement. Once the embalming was completed, the mummified bull was conveyed along the sacred way from Memphis to the necropolis at Saqqara … Bulls were buried in granite sarcophagi, some of which were ornamented, while the bull's mother - who had also been ritually killed and embalmed - was buried in a similar style in the Iseum catacombs dedicated to Isis …

The reason for the bull's death was to join it with Osiris and ritually re-enact the cycle of life, death, and resurrection. The bull had represented the living creator Ptah while it lived and became Osiris when it died and was then referred to as the god Osirapis. Osiris was the first king of Egypt, and the first to die and return to life among all sentient beings, and therefore the ritual act of killing the animal which was so closely associated with kingship and the divine merged the monarchy with resurrection. The death of the Apis bull symbolized the eternal nature of life. Instead of waiting for the bull to die of old age or disease, it was sent to Osiris while still fit, and after it was entombed, a bull looking very much like the last took its place. This new bull would, in fact, house the same eternal spirit as the last since it was believed that the soul of the old bull was reborn in the one that would be chosen to replace it … The bull's death was not the end of its life but a moment of transition from one state to another, and the ceremony which involved its killing was not considered slaughter but transformation.

This ritual might seem to contradict the value ancient Egyptians placed on individuality and a long, full life but, actually, it illustrated that very concept. The bull would never grow old and die - it was an eternal being - and it would remain eternally fit and healthy passing from one body to another in an endless progression. The reason the worship of the Apis bull never significantly altered in over 3,000 years is because it embodied the deepest Egyptian values concerning life, time, and eternity. One's time on earth was only a brief sojourn in an eternal journey which would take one out of time but not out of place … The Apis bull assured people of this by its constancy; no matter the era in which one lived, there had been this divine manifestation before, there was one at the present, and there would be one in the future, and all would be the same entity eternally.

The reason I cited this lengthy excerpt (and had difficulty paring it down from the longer article) is that if Ho’il Moshe’s theory is correct, then every detail of the Apis Bull might shed light on the details of the parah adumah.

For instance:

What might the Torah be getting at by requiring a pristine cow visibly unblemished by black or white—the very colors that qualified the Apis Bull?

Is the Torah’s emphasis on using ashes a deliberate subversion of the Egyptians’ mummification and veneration of the bull’s intact corpse?

What might the contrast between the Apis Bull’s eternity and the parah adumah’s impurity teach us about the Torah’s view of death? Or life?

Is there significance to the “one-at-a-time” requirement for the Apis Bull and the tradition that there will only be ten parah adumah specimens from Moshe to Moshiach? (see Rambam’s Hilchos Parah Adumah 3:4) And could this relate to some contrast between the Egyptian monarchy and the Israelite one?

These are just a few of the speculations that occurred to me as I skimmed various articles about the Apis Bull.

Tzarich Iyun – the Adventure Continues

After discovering Ho’il Moshe’s theory, I assumed that others must have built on it in the 154 years since its publication. But to my surprise, a Google search for the terms “parah adumah apis bull” yields only twelve (!) search results—and unless I’m mistaken, only one of them (“Cow-worship in Egypt and Red Heifer,” from a site called Islamic Scientific Schools) actually discusses both ideas together. “red heifer apis bull” turned up more results, but I didn’t see much from the world of Torah scholarship. Likewise, I expected The Koren Tanakh of the Land of Israel to mention the Apis Bull. But although the Numbers volume includes a section titled “The red cow as a polemic against the cults of the dead,” the Apis Bull goes unmentioned.

In other words, it doesn’t seem like Ho’il Moshe’s theory is very well-known. To my mind, that’s exciting! It points the way to more research to be done, especially given how far Egyptology has come since the late 19th century. If any of you have any insights along these lines, I’d love to hear them!

Bonus for Paid Subscribers

I’ll conclude with a teaser. Ho’il Moshe offers one additional insight in his commentary on the parah adumah: an explanation of the cedar, the hyssop, and the scarlet thread – details the Rambam acknowledged he couldn’t explain. But Ho’il Moshe’s explanation is so bold that I decided not to write about it in my regular dvar Torah article, but instead, to release it as an addendum for paid subscribers only. Stay tuned!

So, whaddaya think? What explanations can you come up with using Ho’il Moshe’s theory as a basis?

Like what you read? Give this article a “like” and share it with someone who might appreciate it!

Want access to my paid content without actually paying? If you successfully refer enough friends, you can get access to the paid tier for free!

Interested in reading more? Become a free subscriber, or upgrade to a paid subscription for the upcoming exclusive content!

If you've gained from what you've learned here, please consider contributing to my Patreon at www.patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss. Alternatively, if you would like to make a direct contribution to the "Rabbi Schneeweiss Torah Content Fund," my Venmo is @Matt-Schneeweiss, and my Zelle and PayPal are mattschneeweiss at gmail. Even a small contribution goes a long way to covering the costs of my podcasts, and will provide me with the financial freedom to produce even more Torah content for you.

If you would like to sponsor a day's or a week's worth of content, or if you are interested in enlisting my services as a teacher or tutor. Thank you to my listeners for listening, thank you to my readers for reading, and thank you to my supporters for supporting my efforts to make Torah ideas available and accessible to everyone.

-----

Substack: rabbischneeweiss.substack.com/

Patreon: patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss

YouTube: youtube.com/rabbischneeweiss

Instagram: instagram.com/rabbischneeweiss/

"The Stoic Jew" Podcast: thestoicjew.buzzsprout.com

"Machshavah Lab" Podcast: machshavahlab.buzzsprout.com

"The Mishlei Podcast": mishlei.buzzsprout.com

"Rambam Bekius" Podcast: rambambekius.buzzsprout.com

"The Tefilah Podcast": tefilah.buzzsprout.com

Old Blog: kolhaseridim.blogspot.com/

WhatsApp Content Hub (where I post all my content and announce my public classes): https://chat.whatsapp.com/GEB1EPIAarsELfHWuI2k0H

Amazon Wishlist: amazon.com/hz/wishlist/ls/Y72CSP86S24W?ref_=wl_sharel

Fascinating. Why do you think there hasn’t been more scholarship about this (from a Jewish POV)?

Can't wait for the addendum!