Chukas: Ultra-Pure Cave Babies, Taylor Swift, and Enriched Uranium

In this article (which needed more than a single page to do it justice) we explore the rationale behind some of the strangest laws of Parah Adumah - strange enough to warrant an equally strange title.

This week's Torah content has been sponsored by Naomi, wishing everyone a joyous summer of continued learning!

If you’re interested in sponsoring some of that learning, email me at rabbischneeweiss@substack.com. If you’d like to help support my writing AND gain access to the upcoming premium content, consider becoming a paid subscriber by clicking the button below.

Chukas: Ultra-Pure Cave Babies, Taylor Swift, and Enriched Uranium

The Parah Adumah (Red Heifer) has the reputation of being one of the most difficult-to-understand mitzvos in the Torah. As the Sefer ha’Chinuch (#397) notes, the most notorious of its mysteries is the fact that whereas the water mixed with the ashes of the Parah Adumah brings taharah (ritual purity) from tumas meis (the ritual impurity associated with a Jewish corpse), it renders tamei all the Kohanim who slaughter, burn, and gather its ashes.

In my opinion, there are other laws which outrank the aforementioned halacha in their strangeness. I am referring to the “extra measures and stringencies” codified by the Rambam in the second chapter of Hilchos Parah Adumah:

Extra measures were taken in the taharah of the Parah Adumah as well as great stringencies in avoiding tumas meis in all the activities [involved in processing it]. Because [the processing of the Parah Adumah] is valid [when performed] by those who immersed [in a mikveh] that same day, [Chazal] were concerned that people would degrade it.

In other words, even though the ashes of the Parah Adumah remove the most severe form of tumah, the taharah-requirements mandated by the Torah for the Kohanim who process the Parah Adumah are minimal. All they need to do is immerse in a mikveh. They don’t even need to wait for the culmination of their taharah at nightfall.

Chazal were concerned that this low bar for taharah would cause the institution of Parah Adumah to be disparaged in the eyes of masses. Imagine, for instance, if a hospital only required a neurosurgeon to wash their hands in tap water before commencing an operation. Such a low standard of hygiene might lead people to conclude that neurosurgery isn’t as big of a deal as it’s made out to be. To counteract this problem, Chazal instituted additional extreme requirements. And when I say “extreme,” I mean EXTRME! Here is a summary of these halachos:

The Kohen who burns the Parah is isolated from his home for seven days in the same way the Kohen Gadol is isolated in preparation for the avodas Yom ha’Kippurim (the Temple Service on Yom Kippur).

This Kohen is quarantined in a room in the azarah (Temple Courtyard) called "the House of Stone" because all the utensils in it were made of stone, which is impervious to tumah. Basically, it’s a hermetically sealed taharah chamber.

His fellow Kohanim are not permitted to touch him, lest they compromise his taharah – even though these Kohanim were unlikely to be tamei, or else they wouldn’t be permitted to enter the Mikdash (Temple) at all.

During these seven days, this Kohen is sprinkled with Parah Adumah ash-water, in the event that he unknowingly contracted tumas meis before his isolation.

Even though ordinary taharah from tumas meis only needs to be done on the third and seventh day, this Kohen is sprinkled with Parah Adumah ash-water EVERY day (except the 4th, for technical reasons).

Not only is he sprinkled with regular Parah Adumah ash-water, but if possible, he is sprinkled with water mixed with ashes from EVERY previous Parah Adumah that had ever been burnt throughout history.

Of course, this sprinkling needs to be done by someone who is tahor, but additionally, it has to be done by someone who has never EVER contracted tumas meis in his entire life. How is it possible to find someone whom we can be certain never contracted tumas meis? (This is where it gets REALLY wacky!)

They would set aside courtyards in Jerusalem built on slabs of stone with hollow space underneath, which would “block” any tumas meis emanating from a “kever tahom” (an unmarked grave in the depths of the earth).

They would bring pregnant women to these stone-floored cells. These women would give birth and raise their children (a.k.a. “the ultra-pure cave babies”) there in a state of taharah-isolation until they were 7 or 8 years old.

When the time comes to process a Parah Adumah, they bring oxen, place large doors on their backs, seat the children on these doors, and lead them down to the Shiloach spring from which the water would be drawn. The purpose of these doors is to create an ohel (tent) to block any potential tumas meis from a kever tahom en route.

When they reach the spring, the children dismount, fill their stone cups (which, as mentioned, were impervious to tumah) with spring water, mount their tumah-proof oxmobiles, and ride up to the Temple Mount.

From there they proceed on foot through the tumah-proof stone courtyards to the pitcher of Parah Adumah ashes, which they would mix with the freshly drawn spring water.

Before they sprinkle the isolated Kohen with the ash-water, the children must immerse themselves in a mikveh – you know, just in case they somehow contracted tumas meis amid their 7 to 8 years of precaution!

Pretty extreme, right? The major question here, in my opinion, is: Are these stringencies “arbitrary”? Granted, these extra measures were introduced to prevent the mitzvah of Parah Adumah from being degraded in the eyes of the people, but are these stringencies merely a series of hoops that need to be jumped through to prevent this outcome, or do they serve a greater philosophical objective as well? And if the latter, what is that objective?

I would like to suggest the following answer: these stringencies are not arbitrary but are consonant with the purpose of tumah and taharah in general.

To understand this, we must answer the question: What is the purpose of the laws of tumah and taharah in general? In his book, Maimonides’ Confrontation with Mysticism (2011), Menachem Kellner divides the Rishonim (medieval commentators) into two camps on this issue.

One camp maintains that tumah is an actual force or property that has an objective, ontological, “real” existence. According to this view, there are physical objects and substances (e.g. corpses, animal carcasses, semen, menstrual blood, etc.) which produce a form of physical or spiritual “contamination” that can only be removed through the proper taharah procedures. To borrow an analogy from Kellner’s book: a Geiger counter is a device which measures radioactivity, which is an invisible but existent property in the physical world. According to this first camp, if it were possible to invent a Geiger-esque “tumah counter” which detected the invisible but existent property of tumah in physical phenomena, the device would begin clicking madly when in the vicinity of a corpse.

The second camp maintains that tumah and taharah are legal constructs which appertain to real-world entities. These constructs serve real-world moral and intellectual objectives, but have no ontological existence, physical or spiritual. The notion of a “tumah counter” would be as absurd as a “copyright detector” or a “physical citizenship test,” since citizenship, copyright, and tumah are legal categories – not properties which inhere in physical objects.

The Rambam belongs to this second camp. He maintains that tumah and taharah are legal constructs – nothing more. Outside of halacha, there is no such thing as tumah and taharah.

The purpose of the elaborate system of tumah and taharah is summarized by the Rambam in a single sentence: “to make people avoid entering the Mikdash (Temple), so that it should be considered as great by the soul and feared and venerated” (Moreh ha’Nevuchim 3:35). He expands upon this theory at length in 3:47:

We have already explained that the whole intention with regard to the Mikdash was to affect those that come to it with a feeling of awe and of fear, as it is stated: "You shall revere My Mikdash" (Vayikra 19:30). Now if one is continually in contact with a venerable object, the impression received from it in the soul diminishes and the feeling it provokes becomes slight. Chazal have already drawn attention to this notion, saying that it is not desirable that the Mikdash should be entered at all times, and in support, they quoted the statement: "Let your foot be seldom in your fellow's house, lest he be sated with you and hate you" (Mishlei 25:17).

This being the intention, He (blessed is He) forbade those who are tamei to enter the Mikdash, despite there being many types of tumah, so that one could – but for a few exceptions – scarcely find a tahor individual. For even if one were preserved from touching neveilah (the carcass of a beast), one might not be preserved from touching one of the eight shratzim (creeping animals) which often fall into dwellings and into food and drink and upon which a man often stumbles in walking. And if one were preserved from that, one might not be preserved from contact with a niddah (a menstruating woman), or a zavah or zav (a woman or a man having a running issue), or a metzora (an individual with the skin-affliction of tzaraas), or their bed. And if one were preserved from that, one might not be preserved from having sexual intercourse with one's wife or from a nocturnal emission. And even if one were purified from these kinds of tumah, one would not be allowed to enter the Mikdash until after sunset. Nor was one allowed to enter the Mikdash at night … and on that night, in most cases, the man in question might have intercourse with his wife or one of the other sources of tumah would befall him, and he would find himself on the following day in the same position as on the day before.

Thus, all of this was a reason for keeping away from the Mikdash and for not entering it at every moment. You know what the Sages said: “Even a man who is tahor may not enter the Hall for the purpose of performing avodah (divine service) before having immersed himself [in a mikveh].” In consequence of such actions, the awe [of the Mikdash] will continue and an impression leading to the intended aim of humility will be produced.

This is why the majority of tumah and taharah laws have no practical relevance today: since these halachos exist primarily to enhance the feeling of awe we experience in the Mikdash by restricting our access, there is no need for these laws in the absence of a Mikdash. This also explains why there is no requirement for ordinary individuals to avoid tumah, and why there’s nothing “bad” about being tamei except insofar as Mikdash is concerned.

We need to read one more layer of the Rambam’s explanation to understand the Parah Adumah stringencies:

To the extent that a certain kind of tumah was more frequent, purification from it was more difficult and was achieved at a later time. Being under the same roof as dead bodies, more especially those of relatives and neighbors, is more frequent than any other kind of tumah. Accordingly, one is purified from it only by means of the ashes of a Parah Adumah, though these are very rare, and after seven days. Running issues and menstruation are more frequent than coming in contact with an individual who is tamei; hence, these require seven days for purification, whereas contact with a person who is tamei requires only one day. The purification of a man or a woman having a running issue and a woman after childbirth was only completed by means of a sacrifice, for such cases are rarer than menstruation.

Somewhat counterintuitively, the reason why tumas meis requires the whole halachic rigamarole of Parah Adumah to remove is not because it is somehow more “severe,” but because it is more commonplace (or at least, it was throughout most of history). The Torah “seized this opportunity,” as it were, to utilize the then-frequent but impactful occurrence of death to further enhance the aura of Mikdash. It did so by designating dead bodies as a source of tumah that could only be removed through the highly demanding requirements of a Parah Adumah.

Based on these excerpts from the Rambam, we can say as follows: just as the laws of tumah and taharah enhance our awe, fear, and reverence by making entry into the Mikdash an exclusive privilege, so too, the extra measures and stringencies surrounding the Parah Adumah increase the psychological air of exclusivity by making the ticket of admission to Mikdash that much more exclusive.

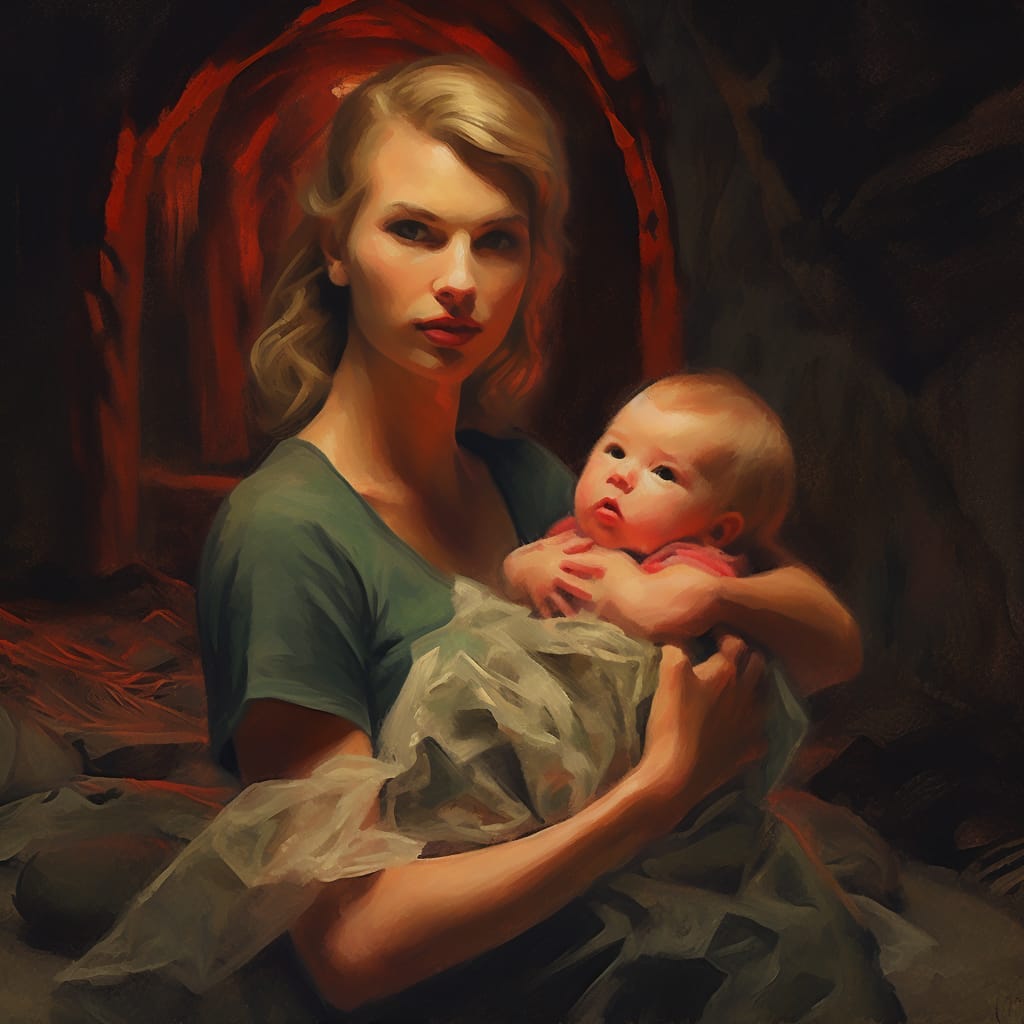

Consider the following mundane, silly, shamelessly clickbaity analogy (that some of you have waited two pages for): Taylor Swift tickets. Such tickets are already difficult enough to obtain, and their scarcity makes her concerts feel that much more exhilarating for the fans who are lucky enough to attend. But imagine if Taylor Swift concert tickets could only be produced through a physical process which required enriched uranium. As exclusive as these tickets currently are, this added requirement would make them feel even more so!

We may not have solved the mystery of the Parah Adumah in this article, but at least we can appreciate how the ultra-pure cave babies and other added stringencies fit into the system of tumah and taharah.

I’m curious: Did you know about these halachos before you read this article? Were you familiar with the Rambam’s explanation of the rationale behind the laws of tumah and taharah? Regardless, what do you think of this explanation? Can you think of a better analogy than Taylor Swift tickets made with enriched uranium? Let me know in the comments!

Like what you read? Give this article a “like” and share it with a friend! Dislike what you read? Share it anyway to spread the dislike!

Want access to my paid content without actually paying? If you successfully refer enough friends, you can get access to the paid tier for free!

Interested in reading more? Become a free subscriber, or upgrade to a paid subscription for the upcoming exclusive content!

If you've gained from what you've learned here, please consider contributing to my Patreon at www.patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss. Alternatively, if you would like to make a direct contribution to the "Rabbi Schneeweiss Torah Content Fund," my Venmo is @Matt-Schneeweiss, and my Zelle and PayPal are mattschneeweiss at gmail.com. Even a small contribution goes a long way to covering the costs of my podcasts, and will provide me with the financial freedom to produce even more Torah content for you.

If you would like to sponsor a day's or a week's worth of content, or if you are interested in enlisting my services as a teacher or tutor, you can reach me at rabbischneeweiss at gmail.com. Thank you to my listeners for listening, thank you to my readers for reading, and thank you to my supporters for supporting my efforts to make Torah ideas available and accessible to everyone.

-----

Substack: rabbischneeweiss.substack.com/

Patreon: patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss

YouTube: youtube.com/rabbischneeweiss

Instagram: instagram.com/rabbischneeweiss/

"The Stoic Jew" Podcast: thestoicjew.buzzsprout.com

"Machshavah Lab" Podcast: machshavahlab.buzzsprout.com

"The Mishlei Podcast": mishlei.buzzsprout.com

"Rambam Bekius" Podcast: rambambekius.buzzsprout.com

"The Tefilah Podcast": tefilah.buzzsprout.com

Old Blog: kolhaseridim.blogspot.com/

WhatsApp Group: https://chat.whatsapp.com/GEB1EPIAarsELfHWuI2k0H

Amazon Wishlist: amazon.com/hz/wishlist/ls/Y72CSP86S24W?ref_=wl_sharel

I agree the Parah Adumah is sacred, entering people unto a death free experience, such as before Adam ate the apple, before Cain killed Able. However, if we can find other ways to follow the guidelines besides raising children in hollow spaces, then we shouldn't a fiori reject it/them. For example, people who are suffix timah mais do not pass along tumah by moving something or holding it (according to the Tosafot YomTov.) Such people could be dressed entirely in plastic and do much of the avodah without contaminating the cow or ashes.

I found it to be a most edifying and entertaining read. Kol HaKavod

I would remark that keeping ones distance from tumah when unrelated to mikdash (ie not around the shalosh regalim when folks are required to make entry), which the Talmud does not seem to have an issue with (bavli RH 16b), is ostensibly related to viewing tumah as something inherently problematic, otoh it may very well just be that folks dont wanna simply view it as an arbitrary way that the Torah increases our estimation of mikdash vkadashav, but rather theres obviously a reason that it is considered anathema at least as far as the mikdash is concerned which I guess is sliding into the ontological perspective . .