Emor / Kedoshim: Should Kids Be Taken to Magic Shows? (COMPLETE version)

This article seeks to answer the question in the title, in light of the strongly worded views of Rambam and Sefer ha'Chinuch. I present my own views with support from R' Moshe Feinstein.

The Torah content from now through Lag ba'Omer has been generously sponsored by Malky M. June is less than a month away which means that I'll soon be transitioning into "summer writing mode," with more substack articles and fewer recorded shiurim. The bulk of these articles will remain free. However, if you would like to support my Torah AND gain access to additional spicy written content, consider becoming a paid subscriber today!

Click here for a printer-friendly version of this article.

Emor / Kedoshim: Should Kids Be Taken to Magic Shows? (COMPLETE Version)

The following PSA was posted in a WhatsApp group. I am sharing it here with the author’s permission:

As we learn from Parshat Kedoshim and as explained by our Rabbis, there is a clear directive against performing magic, as it involves illusions and sleight of hand. The Rambam & Sefer Hachinuch caution us on the damage that attending magic performances can do to a person, particularly our children who are enchanted by such performances. While it isn't specifically forbidden to attend a magic show, it can lead to serious philosophical mistakes and kares (spiritual excision).

The specific prohibition referred to here is “lo teoneinu” (Vayikra 19:26). According to the Sages, the primary meaning is “do not practice astrology” or “do not act in accordance with a belief in lucky or unlucky times.” However, the Rambam (Sefer ha’Mitzvos: Lo Taaseh #32) notes that this lo taaseh includes a second prohibition:

This [injunction of lo teoneinu] also includes an act of achizas eynayim (visual illusions, lit. “grabbing the eyes”). The Sages say: “meonein – this is one who does an act of achizas eynayim” (Sanhedrin 65b). This is a large category of trickery, including sleight of hand which brings people to imagine things that are not real, as we see them doing all the time: [for instance, when a person] takes a rope and, in front of onlookers, tucks it into his cloak and then produces a snake, or one who throws a ring into the air and produces it from the mouth of a person in front of him, and other types of illusions like these which are popular among the masses. Every act of this nature is forbidden. One who does this is called “a performer of illusions,” and because this is a type of kishuf (sorcery), he receives lashes. Not only that, but he deceives people. The harm caused by this is very severe, because things which are completely impossible are rendered possible in the eyes of the ignorant fools, women, and children, accustoming their minds to accept impossible things, thinking they are possible. Understand this.

Sefer ha’Chinuch (Mitzvah #250) expands on the harm mentioned by the Rambam:

Another very great damage lies in this: among the masses and the women and youths, matters which are impossible to the utmost degree will be taken to be possible, and it will delight their minds to accept that the impossible can be without it being a miracle from the Creator; and perhaps the result of this for them will be an evil cause to deny the fundamental [of His Existence] and their souls will be cut off [from eternal life].

Both Rishonim underscore the harm of promoting belief in impossible phenomena, especially for those with impressionable minds. Rambam emphasizes the intrinsic harm: our mind is our only means of apprehending truth, and accustoming one’s mind to accept the impossible as possible is a corruption of that tool. Sefer ha’Chinuch focuses on the theological harm: there is a pleasure in believing that impossible things can be done without the Creator; indulgence in this fantasy-based pleasure predisposes a person to deny His Existence.

On the surface, it seems that taking a child to see a magic show would be ill-advised, even if not outright prohibited. Evidently, the Rambam considered this harm to be so great that he deviated from his typical concise style in the Sefer ha’Mitzvos to point this out. The author of our PSA seems to have a strong position, and there are ample halachic sources to back him up (see Shulchan Aruch YD 179:15, Shach ibid., Pischei Teshuvah ibid. 7).

However, I believe an argument can be made that in the modern era, this reasoning does not apply. To the contrary, the children whose parents do not take them to magic shows are at even greater risk of the harms mentioned by the Rambam and Sefer ha’Chinuch.

I am not a posek, and my halachic speculations should not be regarded as psak, especially because I haven’t learned through the entire sugya (topic). I am sharing my view purely for its theoretical, not practical, value.

For most of history, people believed in magic. This was especially true in the ancient Near East, where the practice of magic was ubiquitous. In such a world, it could be assumed that the average man, woman, or child who witnessed sleight of hand would believe it to be real magic. This is why the Torah forbade achizas eynayim.

However, humanity has undergone drastic changes since then, including the Scientific Revolution, the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution and subsequent technological booms, the rapid secularization of the 20th century, and the Information Age, to name a few. Each of these cultural upheavals contributed to the erosion of the pagan, mythological, and supernatural worldview which allowed the widespread belief in magic to flourish.

There was another societal change that is far less known but relevant to our topic. It was brought about by a man named Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin (1805-1871), known as “the father of modern magic.” In his day, magic was the stuff of fairgrounds and charlatans. He singlehandedly elevated it to an art performed on stage. The concept you think of when you hear the word “magician” was invented by him.

In light of this, my argument is that even the Rambam would not categorically forbid sleight of hand. To restate his formulation in the Sefer ha’Mitzvos: the Torah only prohibits “sleight of hand which brings people to imagine matters which are not real.” As noted above, throughout most of history, all sleight of hand would fall into this category. But in a scientific, post-Enlightenment, technologically advanced, secular era in which stage magic is an established form of entertainment and magicians’ secrets are accessible with a quick Google search, only a small minority of people are prone to mistaking achizas eynayim for real magic.

The truth of this new status quo is evident when one considers the default response of a normal person upon witnessing such “magic.” The average audience member at a magic show does not react by fearing or revering the magician for his supernatural powers, as they might have done in the pre-modern era. Instead, their default reaction is to wonder, “How did he do that?” No matter how amazed they are, they know it is a trick. And when they ask the magician to do it again and he refuses, they know it is because he does not want to give them an opportunity to figure out his secret. Similarly, consider the questions people do not ask. When a magician pulls a rabbit out of a hat, nobody even thinks to ask him to conjure a rabbit out of thin air without a hat. Everyone knows that his trick requires subterfuge, which necessitates concealment. Likewise, nobody inquires into the magician’s beliefs, religion, or lifestyle. They know he is an entertainer, and that his art has nothing to do with the supernatural. (This is not true, for instance, with astrologers, psychics, tarot card readers, and other practitioners of the occult who are still regarded as genuine even in the modern era. I am only speaking here about magicians.)

Whenever I’ve read the Rambam’s statements about meonein, I always assumed he would agree with this line of reasoning, but I had never looked into the practical halacha in contemporary sources. Thankfully, we have a professional magician in our community who is also a rabbi. When the PSA was posted on WhatsApp, his wife shared a source sheet featuring a responsum of R’ Moshe Feinstein (Iggros Moshe: Yoreh Deah 4 13:1) on this exact question. The responsum is too long for me to include here, and the “translated” excerpts on the source sheet are too inexact for my standards. Here is my translation of the concluding paragraphs:

[The foregoing] is what I have said by way of learning (i.e., theoretical analysis). However, I would not give in response to a shailah (halachic question) a horaah (practical ruling) that there is no prohibition on achizas eynayim through sleight of hand or similar means. For in any case, if the performer deceives others and claims to do things supernaturally, it must be forbidden, as it can mislead people into believing he is a miracle worker. Such a person is certainly unfit to be learned from even if he did not lie, and certainly if he did. Even without lying and saying that it is a natural phenomenon, that God gave him greater agility than others, he should not show this to people except in a way that they see and recognize that it is nothing but extreme dexterity; he should not perform it in a way that people cannot see or recognize, leading them to think it is sorcery rather than a natural skill. This constitutes a meisis (inciter) for sorcery, which is prohibited even if others don’t heed him …

In other words, Rav Moshe argues that an act of achizas eynayim is certainly prohibited if its practitioner claims to be doing something supernatural. This is the basis on which Rav Moshe stakes his major argument:

However, it is relevant to consider permitting entertainers who perform sleight of hand tricks at weddings in a manner that it is well-known and publicized that it is due to dexterity and similar [techniques], which are natural acts unrelated to sorcery … This would only be subject to prohibition for the entertainers if they claim to act by means of some incantations, even if these incantations are not related to sorcery … but if they claim to do it naturally – and it is, indeed, well-known and publicized as such – I see no prohibition in it.

This argument is similar, albeit not identical, to my position stated above. I argued that in the modern era, virtually nobody thinks that the magic performed by entertainers is real, and since achizas eynayim is only prohibited if it leads people to such a belief, then stage magic is no longer categorically forbidden. Rav Moshe agrees that the true nature of stage magic is “well-known and publicized” to the point where entertainers can perform without straying into meonein territory, provided that they don’t overtly convey the impression that they possess real powers (e.g., by using incantations or claiming to do supernatural feats).

Despite the force of his argument, Rav Moshe makes it clear that he is not issuing an official ruling on this matter. He closes his responsum with one of the most psak-laden statements of non-psak I’ve ever read:

Nevertheless, this matter has never come to me [as a question of] practical halacha, nor have I heard of such [a form of] entertainment being done here at all. At weddings I attended where there was an entertainer, they did not engage in such acts. Therefore, this is only a theoretical discussion and not for practical ruling, even though I have no doubt in the halacha. If this matter were to come before me in practice, I would defer to the honor of our esteemed Rabbis who prohibit. If evasion were impossible, I would rule that if it is done naturally, and it is known and publicized as natural, it is permitted.

He concludes by dismissing an objection based on the concern that impressionable children will be led astray:

Regarding what [the questioner] added, that it is known that many children are amazed by [magic] to the point that they believe the person must have supernatural powers – this is an exaggeration. Rather, children think that the person is very great (i.e., skilled), and there are surely children who believe there are many others like him, and this is not a concern.

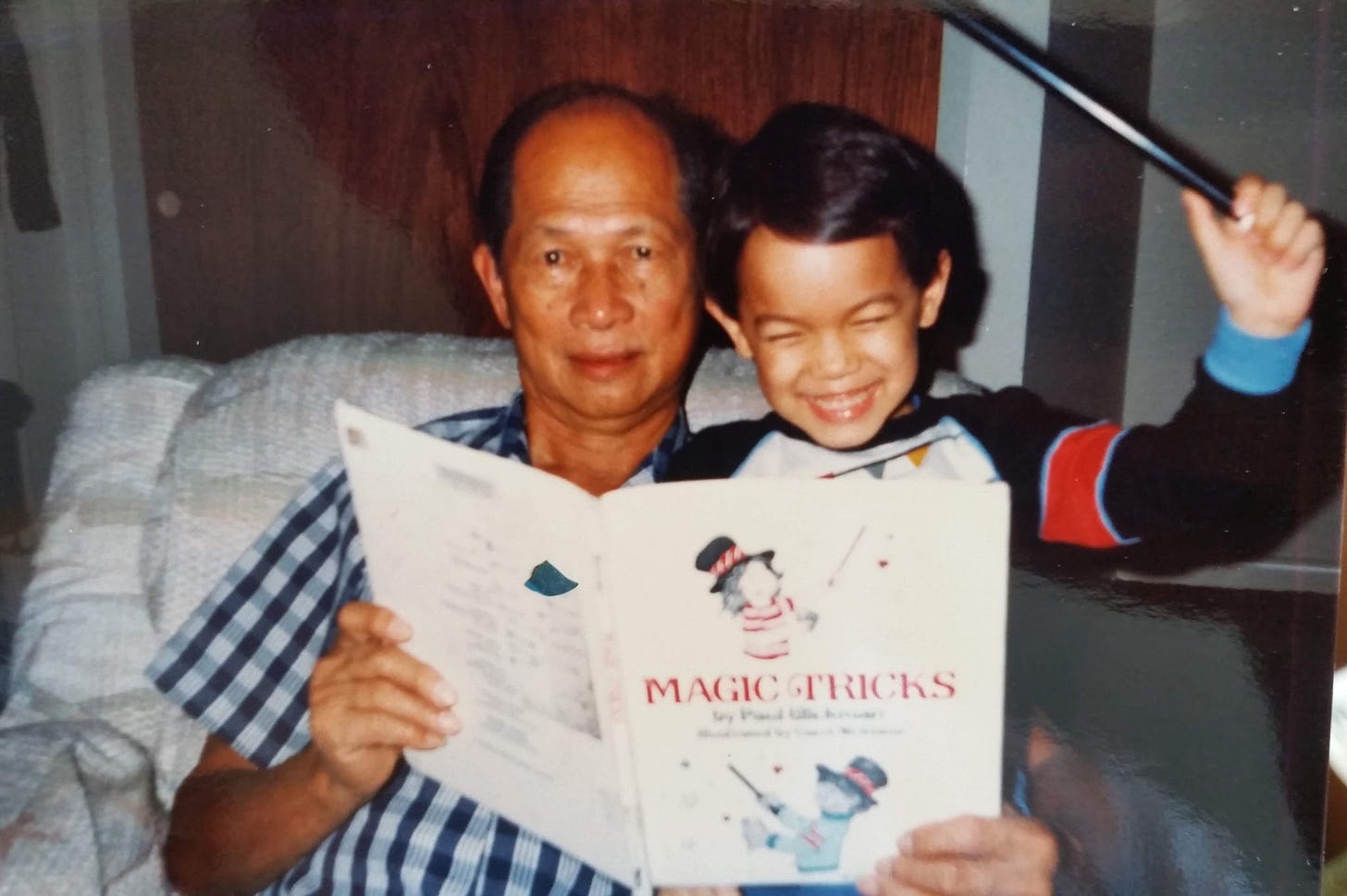

This brings me to my final point. Taking a child to see a magic performance used to be risky or downright hazardous for the reasons mentioned by the Rambam and the Sefer ha’Chinuch. Today, I believe that the opposite is true. Imagine two children. One of them has been exposed to magic shows from an early age. His parents tell him that magic isn’t real and that magicians are just skilled artists. They show him how such tricks are done, and maybe even teach him how to do magic tricks himself.

The second child is shielded from all exposure to magic throughout his childhood and is told that this is a serious prohibition related to avodah zarah – despite the fact that all his friends get to watch the magician perform at his friend’s birthday party or school chagigah. He picks up on the vibe from his parents that this is not only bad but dangerous. He is never allowed to feel what it’s like to be astonished by an illusion and subsequently shown how it was done – an experience that drains all the mystery by exposing the mundane mechanics. Consequently, he never develops the intuition which would allow him to quickly see through even the most amazing feats and instinctively relate to them as the achizas eynayim that they are.

Which of these two children is more in danger of succumbing to the allure of magic and which one is better equipped to recognize the truth? I leave it to the reader to decide.

(Reminder: I initially set out to write this article for Parashas Emor and promised to draw a thematic connection between Emor and Kedoshim, where the prohibition of meonein appears. It is now Parashas Behar, so I suppose I missed the boat again. Still, I’m going to follow through on what I promised!)

What does any of this have to do with Parashas Emor? In a word: Kohanim, or “Jewish priests.” The first two chapters of Emor detail dozens of laws which are specific to these priests. Here is an excerpt from Dr. Racheli Shalomi-Hen’s commentary on Shemos 7:11 in The Koren Tanakh of the Land of Israel: Exodus:

Since magic was part and parcel of religion and science, the chief lector priests were known for their magical skills. In ancient Egyptian literature, lector priests attended the king. They were called to the palace whenever the king needed their help. In literature of legendary nature, they always managed to overcome problems using impressive magic or a series of magical deeds … The exclusive skills and knowledge of lector priests were highly valued in ancient Egyptian society. From ancient Egyptian tomb inscriptions, we know that their immersion in the realm of magic and literacy was believed to give them the power to cast fatal curses. The combination of their knowledge and their magical skills, known only to them, must have inspired fear and awe among those who interacted with them.

In stark contrast to the priests in Egypt and the rest of the ancient world, the role of our Kohanim had nothing to do with magic. They, like the rest of the Israelites, were forbidden to engage in such practices. They were not summoned to cast spells, work miracles, utter curses, or read omens. Their primary role was to facilitate avodah ba’Mikdash (Temple service) “and to teach the Children of Israel all the decrees that Hashem had spoken to them through Moshe” (Vayikra 10:11).

In conclusion, the evolution of magic from an ancient practice shrouded in mystery to a modern form of entertainment ought to compel us to reexamine the practical halacha regarding the Torah prohibition of meonein. While this prohibition remains in force, an argument can be made that its scope is far more limited than it once was. The statements made by Chazal and the Rishonim about achizas eynayim were rooted in a context where magic was genuinely believed to be supernatural. Our contemporary understanding and transparency about these performances have shifted the status quo. By educating our children about the nature of magic as an art form rather than shielding them from it, we equip them with the critical thinking skills necessary to discern reality from illusion. By incorporating exposure to magic from an early age, we instill the message in our children that “all these crafts which the Torah forbade are not branches of wisdom, but rather, emptiness and vanity which attracted the feebleminded and caused them to abandon all the paths of truth” (Rambam, Hilchos Avodah Zarah 11:16).

If you’re interested in the shiur version which led to this article, here’s the video:

So, what do you think? Should we avoid taking our kids to magic shows? And if so, do you think the Rambam would agree?

Like what you read? Give this article a “like” and share it with someone who might appreciate it!

Want access to my paid content without actually paying? If you successfully refer enough friends, you can get access to the paid tier for free!

Interested in reading more? Become a free subscriber, or upgrade to a paid subscription for the upcoming exclusive content!

If you've gained from what you've learned here, please consider contributing to my Patreon at www.patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss. Alternatively, if you would like to make a direct contribution to the "Rabbi Schneeweiss Torah Content Fund," my Venmo is @Matt-Schneeweiss, and my Zelle and PayPal are mattschneeweiss at gmail. Even a small contribution goes a long way to covering the costs of my podcasts, and will provide me with the financial freedom to produce even more Torah content for you.

If you would like to sponsor a day's or a week's worth of content, or if you are interested in enlisting my services as a teacher or tutor. Thank you to my listeners for listening, thank you to my readers for reading, and thank you to my supporters for supporting my efforts to make Torah ideas available and accessible to everyone.

-----

Substack: rabbischneeweiss.substack.com/

Patreon: patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss

YouTube: youtube.com/rabbischneeweiss

Instagram: instagram.com/rabbischneeweiss/

"The Stoic Jew" Podcast: thestoicjew.buzzsprout.com

"Machshavah Lab" Podcast: machshavahlab.buzzsprout.com

"The Mishlei Podcast": mishlei.buzzsprout.com

"Rambam Bekius" Podcast: rambambekius.buzzsprout.com

"The Tefilah Podcast": tefilah.buzzsprout.com

Old Blog: kolhaseridim.blogspot.com/

WhatsApp Content Hub (where I post all my content and announce my public classes): https://chat.whatsapp.com/GEB1EPIAarsELfHWuI2k0H

Amazon Wishlist: amazon.com/hz/wishlist/ls/Y72CSP86S24W?ref_=wl_sharel

I think you hit the nail on the head. As for the role of the kohanim, I always like to point out that in many ways, it's the opposite of the role of Egyptian priests, who dealt in closely guarded mysteries. In contrast, every single thing that the kohanim were tasked with is spelled out for all to see in the Torah, the world's first Freedom of Information Act. As Shadal put it, Judaism is "una religione senza misteri" -- a religion without mysteries. And as I see it, the sin of Nadav and Avihu was their attempt to come up with their own private ritual that was not part of the publicly revealed routine.

Great post!