Emulating Darwin: A Jewish Approach to Seeking God

I recently read some Darwin for the first time and was so impressed by the character reflected in his writing that I was moved to write this article.

The Torah content for this week has been sponsored by an anonymous librarian who has helped me on many occasions by providing me with articles, texts, and books which have enriched my learning and teaching. Thank you!

Click here for a printer-friendly version of this article.

Emulating Darwin: A Jewish Approach to Seeking God

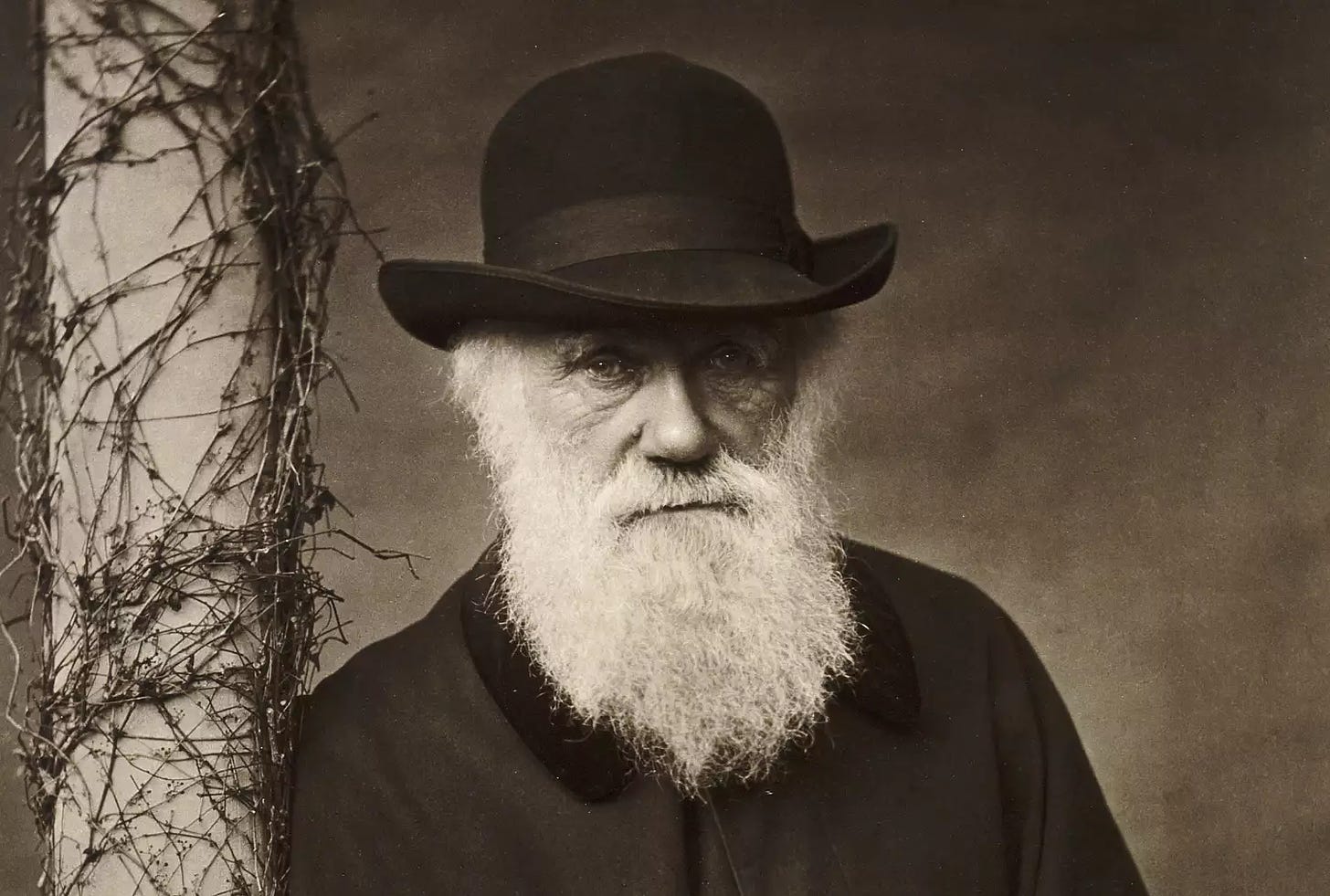

The name of Charles Darwin (1809-1882) came up several times in my reading and podcast listening last week. This Shabbos, on a whim, I decided to pick up my copy of On the Origin of Species. Although I only read through the Table of Contents, the preface, and the introduction, I came away with some thoughts I wanted to share.

As luck would have it, on this day exactly 166 years ago (June 18, 1858), Darwin received a letter from Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913) outlining a theory of natural selection which was similar to his own. It was this letter that prompted Darwin to publish his own findings.

Guiding Principles

An epigraph is a short quotation or saying at the beginning of a book or chapter, intended to suggest its theme. Darwin prefaced his work with three:

But with regard to the material world, we can at least go so far as this – we can perceive that events are brought about not by insulated interpositions of Divine power, exerted in each particular case, but by the establishment of general laws.

- Whewell: Bridgewater Treatise

The only distinct meaning of the word 'natural' is stated, fixed, or settled; since what is natural as much requires and presupposes an intelligent agent to render it so, i.e., to effect it continually or at stated times, as what is supernatural or miraculous does to effect it for once.

- Butler: Analogy of Revealed Religion

To conclude, therefore, let no man out of a weak conceit of sobriety, or an ill-applied moderation, think or maintain, that a man can search too far or be too well studied in the book of God's word, or in the book of God's works; divinity or philosophy; but rather let men endeavour an endless progress or proficience in both.

- Bacon: Advancement of Learning

Darwin’s view of God and creation evolved developed significantly over the course of his studies, as Timothy Ferris chronicles in Coming of Age in the Milky Way (1988):

When Darwin left England, he was still a creationist. He did “not then in the least doubt the strict and literal truth of every word in the Bible,” he recalled, and believed, as did most of the geologists and biologists of his day, that all species of life had been created simultaneously and individually. He returned home with doubts on this score. He had seen firsthand evidence that the earth is embroiled in continuing change, and he wondered whether species might change, too, and whether their mutability might cause new species to come into existence. (p.235)

The first epigraphical quotation, from English polymath William Whewell (1794-1866), reflects what must have been one of the first major shifts in Darwin’s view of God in relation to the universe. Whereas the simple religious man looks for God’s glory in displays of miraculous power, the true man of God sees His wisdom in the fabric of the universe. It is easy to appreciate the “great power and strong hand” (Shemos 32:11) of God when contemplating His supernatural interference in nature, but the appreciation of nature itself requires an above-average level of knowledge, as David ha’Melech exclaims: “How great are Your works, Hashem! [How] very deep are Your thoughts! A boorish man doesn’t know, and a fool doesn’t understand this” (Tehilim 92:6-7).

Rambam laments the gulf between these two types of individuals in the Moreh ha’Nevuchim 2:6:

How blind, how perniciously blind, are the naïve! If you told one of the self-professed sages of Israel that God sends an angel that enters a woman’s womb and forms the fetus there, he would be awestruck and take it as a mark of God’s greatness and power – and wisdom – although convinced that an angel is a body of raging fire one-third the size of the entire world. All this he thinks possible for God. But if you told him that God gave the semen the power to shape, form, and configure these organs and that this power is the angel … he would recoil. For he fails to grasp that true power and greatness lie in creating the powers active in things even if imperceptible. (trans. Goodman)

The second quotation, from theologian Joseph Butler (1682-1752), complements the first. Through it, Darwin acknowledges that the Creator has no less of a hand in the natural than in the miraculous. To the contrary – His role in the former is even greater and more impressive. Malbim articulates this in his commentary on Tehilim 93:1:

[Hashem governs] His world through two types of governance: the fixed natural governance (hanhagah ha’kavua ha’tivis) and the miraculous providential governance (hanhagah ha’nisis ha’hashgachiyis) that occurs according to the moment and need … It is evident from reasoning that fixed natural governance shows greater strength than a miracle, which is only temporary. Fixed natural governance demonstrates His great strength, as the world stands firm on these laws forever. However, the miracle does not exhibit the same strength, as it is only temporary. It is not more powerful to command the sea to stand still as a wall of water at the time of the Exodus than to command the sea at creation to flow downwards, since both were done by the power of Hashem. Nature is a constant miracle, and the miracle is temporary nature. If we call a miracle that which occurs not by its own power but by the word of Hashem, then nature is also a constant miracle, as natural power is not from itself but from the word of Hashem Who sustains it. There is no difference between nature and a miracle, except that in nature, the power is set permanently, and in a miracle, it is set temporarily.

In 1873, fourteen years after the publication of On the Origin of Species, Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch employed this thought to assuage the misgivings of Jews who feared that the acceptance of natural selection would eliminate God from the equation. Hirsch writes:

Even if this notion [of Darwinian evolution] were ever to gain complete acceptance by the scientific world … Judaism in that case would call upon its adherents to give even greater reverence than ever before to the one, sole God Who, in His boundless creative wisdom and eternal omnipotence, needed to bring into existence no more than one single, amorphous nucleus, and one single law of “adaptation and heredity” in order to bring forth, from what seemed chaos but was in fact a very definite order, the infinite variety of species we know today, each with its unique characteristics that sets it apart from all other creatures. (“The Educational Value of Judaism,” Collected Writings, vol. VII, p. 264)

The third quotation, from English philosopher Francis Bacon (1561-1626), conveys a warning as relevant today as it was at the dawn of the Scientific Revolution. There are many people whose sole interest is either in “the book of God’s word” or in “the book of God’s works.” How many people give both books their due, or even attempt to do so? Too few.

The Rambam is one of those people. In his formulation of the mitzvah of ahavas Hashem (love of God) in the Sefer ha’Mitzvos (Aseh #3), he emphasizes the study of Torah:

The third positive mitzvah is that He commanded us regarding love of Him, namely, that we think about and contemplate His commandments, His statements, and His actions until we apprehend Him and derive the greatest pleasure from that apprehension, and that is the love that is obligatory. This is the language of Sifrei (Piska 33): “Since it is stated, 'you shall love [Hashem, your God]' (Devarim 6:5), I would not know how a person can love God. [Therefore,] the Torah teaches: 'And these things that I command you today shall be upon your heart' (ibid. 6:6) - that through this, you will recognize the One Who spoke and the world came into being.”

In the formulation in the Mishneh Torah (Hilchos Yesodei ha’Torah 2:2-3), Rambam emphasizes the study of nature:

What is the way of loving Him and fearing Him? When a person contemplates His great and wondrous works and creations and sees from them His wisdom which is incomparable and infinite, he immediately loves, praises, and extols and is filled with a great desire to know the Great Name, as David said: “My soul thirsts for God, for the living God” (Tehilim 42:3).

And when he thinks about these same matters, he immediately recoils with awe and fear and knows that he is a small, insignificant, dim creature, standing with a frail and puny mind in the presence of [a Being of] Perfect Knowledge, as David said: “[When I behold Your heavens, the work of Your fingers, the moon and stars that you have set in place, I exclaim,] ‘What is frail man that You should notice him, [and the son of mortal man that You should take note of him?’]” (ibid. 8:4-5).

Based on these concepts, I will now explain important principles regarding the works of the Master of Worlds to provide an introduction for a person of understanding to [develop] love for God, as the Sages said regarding love: "In this manner, you will recognize the One Who spoke and the world came into being."

The three quotations in Darwin’s epigraph show a man whose quest to understand the natural world stemmed from a desire to draw near to his Creator. David wrote: “Hashem from heaven looked down on the sons of mankind to see whether there is an intelligent man seeking God” (Tehilim 14:2). Darwin was such a man.

Humility

Here are the opening paragraphs of Darwin’s introduction, with my emphasis in bold:

When on board H.M.S. Beagle as naturalist, I was much struck with certain facts in the distribution of the organic beings inhabiting South America, and in the geological relations of the present to the past inhabitants of that continent. These facts, as will be seen in the latter chapters of this volume, seemed to throw some light on the origin of species – that mystery of mysteries, as it has been called by one of our greatest philosophers. On my return home, it occurred to me, in 1837, that something might perhaps be made out on this question by patiently accumulating and reflecting on all sorts of facts which could possibly have any bearing on it. After five years’ work I allowed myself to speculate on the subject, and drew up some short notes; these I enlarged in 1844 into a sketch of the conclusions, which then seemed to me probable: from that period to the present day I have steadily pursued the same object. I hope that I may be excused for entering on these personal details, as I give them to show that I have not been hasty in coming to a decision.

My work is now (1859) nearly finished; but as it will take me many more years to complete it, and as my health is far from strong, I have been urged to publish this abstract … This abstract, which I now publish, must necessarily be imperfect. I cannot here give references and authorities for my several statements; and I must trust to the reader reposing some confidence in my accuracy. No doubt errors will have crept in, though I hope I have always been cautious in trusting to good authorities alone. I can here give only the general conclusions at which I have arrived, with a few facts in illustration, but which I hope, in most cases will suffice. No one can feel more sensible than I do of the necessity of hereafter publishing in detail all the facts, with references, on which my conclusions have been grounded; and I hope in a future work to do this. For I am well aware that scarcely a single point is discussed in this volume on which facts cannot be adduced, often apparently leading to conclusions directly opposite to those at which I have arrived. A fair result can be obtained only by fully stating and balancing the facts and arguments on both sides of each question; and this is here impossible.

If there’s one quality that shines through in these two paragraphs, it is Darwin’s remarkable intellectual humility. It is clear how reticent he is to say anything without a firm basis in the facts. One would like to think that this quality would be shared with every scientist, but in Darwin’s case, this was part of his personality. Ferris (ibid. p.232) cites the testimony of Darwin’s walking companion, Dr. Edward Lane, who wrote about his friend:

Nothing escaped him. No object in nature, whether Flower, or Bird, or Insect of any kind, could avoid his loving recognition. He knew about them all … could give you endless information … in a manner so full of point and pith and living interest, and so full of charm, that you could not but be supremely delighted, nor fail to feel … that you were enjoying a vast intellectual treat never to be forgotten.

Of course, even Darwin had his limits, but that didn’t stop him from doing his due scientific diligence. An amusing example of this can be seen in his barnacle research, as reported in an article from the National Park Service:

The whole process of barnacle reproduction so fascinated renowned naturalist Charles Darwin that he intimately studied them, practically on a daily basis, from 1846 to 1854. Ultimately, Darwin’s deep and focused research on barnacles resulted in the publication of a 4-volume study about them. His fascination and fondness for the less-than-effervescent personalities of these crusty critters appears to have waned over his years of research (see quote), but many historians credit this work on barnacles as a key component to his formulation of the theory of speciation he wrote about in 1859’s On the Origin of Species.

The quotation referenced in the article is from a letter Darwin wrote to a friend in 1852, which reads:

I am at work on the second volume of the Cirripedia, of which creatures I am wonderfully tired: I hate a Barnacle as no man ever did before, not even a Sailor in a slow-sailing ship.

But Darwin was not a man who would let his hatred of barnacles impede his quest for knowledge.

Irony

Despite the nearly universal acceptance of Darwin’s theories in the scientific community, his views are still opposed by many adherents of the world’s religious population. How do these objectors measure up to the man they shun? How many of these people are as dedicated to the study of both Divine books as Darwin? How many arrived at their conclusions after years of investigation and contemplation, as Darwin did in arriving at his?

There is an irony here: those who reject Darwin’s theories often do so in the name of God, yet Darwin himself was, by Judaism’s standards, the type of person who achieved closeness to God. Darwin’s scientific journey and religious odyssey were one and the same. One can imagine God delivering a similar rebuke to these people as He did to the friends of Iyov: “My wrath burns against you, for you did not speak properly about Me as My servant Darwin did” (cf. Iyov 42:8).

Darwin’s dedication to truth and love of God should inspire us all.

If you have any other insight into Darwin’s character along these lines, please share!

Like what you read? Give this article a “like” and share it with someone who might appreciate it!

Want access to my paid content without actually paying? If you successfully refer enough friends, you can get access to the paid tier for free!

Interested in reading more? Become a free subscriber, or upgrade to a paid subscription for the upcoming exclusive content!

If you've gained from what you've learned here, please consider contributing to my Patreon at www.patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss. Alternatively, if you would like to make a direct contribution to the "Rabbi Schneeweiss Torah Content Fund," my Venmo is @Matt-Schneeweiss, and my Zelle and PayPal are mattschneeweiss at gmail. Even a small contribution goes a long way to covering the costs of my podcasts, and will provide me with the financial freedom to produce even more Torah content for you.

If you would like to sponsor a day's or a week's worth of content, or if you are interested in enlisting my services as a teacher or tutor. Thank you to my listeners for listening, thank you to my readers for reading, and thank you to my supporters for supporting my efforts to make Torah ideas available and accessible to everyone.

-----

Substack: rabbischneeweiss.substack.com/

Patreon: patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss

YouTube: youtube.com/rabbischneeweiss

Instagram: instagram.com/rabbischneeweiss/

"The Stoic Jew" Podcast: thestoicjew.buzzsprout.com

"Machshavah Lab" Podcast: machshavahlab.buzzsprout.com

"The Mishlei Podcast": mishlei.buzzsprout.com

"Rambam Bekius" Podcast: rambambekius.buzzsprout.com

"The Tefilah Podcast": tefilah.buzzsprout.com

Old Blog: kolhaseridim.blogspot.com/

WhatsApp Content Hub (where I post all my content and announce my public classes): https://chat.whatsapp.com/GEB1EPIAarsELfHWuI2k0H

Amazon Wishlist: amazon.com/hz/wishlist/ls/Y72CSP86S24W?ref_=wl_sharel

I haven't read much Darwin, but I also have been moved by what I have read by him. Interesting article and thank you for collecting your thoughts and these sources!

If Darwin epitomized so many of our religious ideals, why do you think it is that he and his theories seem to have the opposite reputation?