Freddie Mercury, Shadal, and the Crisis of Human Finitude

What do Freddie Mercury and Shadal have in common? And what does this have to do with us? More than one might imagine. I'm certainly speaking for myself, but I hope I'm speaking for all of us.

The Torah content for the month of July has been sponsored by the Richmond, VA learning community, “with appreciation for Rabbi Schneeweiss’s stimulation of learning, thinking, and discussion in Torah during his scholar-in-residence Shabbos this past June.” Thank YOU, Richmond, for your warmth, your curiosity, and your love of Torah! I'm already excited for my next visit!

Click here for a printer-friendly version of this article.

Freddie Mercury, Shadal, and Human Finitude

Freddie Mercury’s Final Years

Last night I saw the movie Bohemian Rhapsody (2018) for the first time. In the final act, Mercury reunites with his bandmates for the Live Aid concert. At the end of their first rehearsal, he informs them of his great secret: he has AIDS. Here’s the scene, featuring the inimitable performance of Rami Malek:

For those who opt not to watch the video, here’s what happens. Upon seeing the sadness and sympathy in the eyes of his friends, Freddie chastises them, saying:

Please, if any of you fuss about it or frown about it, or worst of all, if you bore me with your sympathy, that's just seconds wasted. Seconds that could be used making music, which is all I want to do with the time I have left. I don't have time to be anybody's victim, AIDS poster boy, or cautionary tale. No, I decide who I am. I'm going to be what I was born to be: a performer that gives the people what they want: a touch of the heavens! Freddie f**king Mercury.

Strange as it may sound, my first association upon hearing this was not to the teachings of Stoicism nor to the words of Shlomo ha’Melech in Koheles, but to a passage from the personal correspondence of Shadal.

Shadal’s Final Years

This past Shabbos I began reading Let Him Bray: The Stormy Correspondence of Samuel David Luzzatto and Elia Benamozegh, by Daniel A. Klein, originally published in Ḥakirah (available as a PDF here) and republished as an appendix to his Shadal on Numbers (2023, Kodesh Press).

First, some context. In 1826, Shadal wrote Vikkuaḥ al Ḥokhmat ha-Kabbalah, in which he presented his arguments against the authenticity and validity of the Zohar and its teachings. Klein explains why the correspondence between Shadal and Benamozegh didn’t erupt until decades later:

Concerned that publicizing these views might undermine the simple faith of the pious, Shadal withheld the Vikkuaḥ from publication until 1852. This is one reason why Elia Benamozegh offered no response to it in 1826. The other reason is that in 1826, Benamozegh was only three years old.

Benamozegh (1823-1900), himself a kabbalist, published a lengthy refutation of the Vikkuaḥ in 1862 entitled Taam le-Shad — a reference to the Torah’s description of the mahn in Bamidbar 11:8 (“ke’taam le’shad ha’shamen, the flavor of soft oiled dough“) doubling as a pun meaning “reasoning in response to shin daled,” as in Shmuel David (a.k.a. Shadal). Benamozegh subsequently wrote a pamphlet in which he criticized Shadal’s overall approach to Judaism. Klein writes:

Shadal made no public response to this provocation, but he gave vent to his feelings in a letter to an unidentified third party. Expressing his preference to refrain from attacking Benamozegh in the open, Shadal said, Penso lasciarlo ragliare — “I intend to let him bray.”

When word of this remark reached Benamozegh, he wrote a letter to Shadal in the spirit of the verse: לֹא תִשְׂנָא אֶת אָחִיךָ בִּלְבָבֶךָ הוֹכֵחַ תּוֹכִיחַ אֶת עֲמִיתֶךָ וְלֹא תִשָּׂא עָלָיו חֵטְא “Do not hate your brother in your heart; you shall surely rebuke a member of your people, and you shall not bear a sin” (Vayikra 19:17). This letter sparked a fiery correspondence between the two men, which lasted from 1863 through 1864. Klein provides an important piece of background information about this time period in a footnote:

Shadal was 63 and in failing health when he wrote this letter, and in fact he had only two more years to live. A few months previously, he had written to one of his students, “I am exhausted by old age and by melancholy … Nevertheless, I persevere in my work. I do not wish to lose a solitary day, for who knows who few are the days left in me? I must consolidate my work and get it published” (Epistolario, p.1017, quoted in Margolies, Samuel David Luzzatto, p.54)

It was Shadal’s initial response to Benamozegh which I associated to upon hearing the words of Malek’s Mercury. Shadal begins:

Most esteemed friend,

I received some time ago the Ta’am le'-Shad, and I did not write you so as not to enter into useless disputes. I was asked if I intended to respond, and I said no. And so it is. The little life and strength that are left to me I wish to employ in endeavoring to leave to posterity a little more truth and a little less error, and not in further controversies. Let anyone combat me who so desires; let anyone mistreat me at his pleasure; I will not waste my time in defending myself; I would be deflected from my mission, which is to discover new things. As long as there exists one verse in the Holy Scriptures that is not understood exactly, I must not think of defending my writings. Truth and time will defend them.

Despite knowing that Shadal wrote these letters in a characteristically flowery and passionate Italian style, my eyes still teared up when I read his words. What nobility! What humility in the face of human finitude! What a sense he conveyed of the gravity of responsibility articulated in Chazal’s statement:לֹא עָלֶיךָ הַמְּלָאכָה לִגְמֹר, וְלֹא אַתָּה בֶן חוֹרִין לִבָּטֵל מִמֶּנָּה “The labor is not upon you to complete, nor are you free to be idle from it” (Avos 2:16). Here was a man who knew who he was and lived his life deliberately.

My intention is not to equate Shadal with Freddie Mercury (as depicted in the film), God forbid. But there is one respect in which both men are equal: sensing they were close to death, each decided to be what he was born to be, committed himself to living that life, and vowed not waste what precious time he had left.

This, in turn, led me to reflect on my own life.

My Final Years

God willing, I have many years of life left in me … but I have no way of knowing whether God wills this. As Gandalf the Grey said, “That is not for us to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”

For me, these past three years (post-Shalhevet, a”h) have been about fulfilling Dolly Parton’s injunction, “Find out who you are and do it on purpose.” I honestly can’t tell whether I’m still in the exploratory phase of that journey, or whether I’m in the implementation phase, or whether the two are the same, or whether they’re different but there’s no real way to tell the difference, or whether I’m misguided in my attempt to even try to discern the difference. All I know is that I’m on the right track. Or at least, I try to be on the right track, and I right myself whenever I realize I’ve veered. That is the most I can do.

Three things have happened over the past year or so which changed my relationship with my own mortality. The first event that happened was this past January 10th, when I turned 39. I am now living out my 40th year of existence, which is half of the “mighty” lifespan according to the verse: יְמֵי שְׁנוֹתֵינוּ בָהֶם שִׁבְעִים שָׁנָה וְאִם בִּגְבוּרֹת שְׁמוֹנִים שָׁנָה “The days of our years among them are seventy years, and if with might, eighty years” (Tehilim 90:10). When your tank is at least halfway empty, there’s no denying the inevitability that it will one day be completely empty.

The second thing that happened is that a bunch of people in my life died. First and foremost among them was my rebbi, Rabbi Morton Moskowitz zt”l in May 2022. This was followed in Spring 2023 by the deaths of Popo (my grandmother, 1924-2023), Adira (my student, 2004-2023), Julie Bass (my talmid’s mother, 1969-2023), and Alan (my friend, also 1924-2023). Their passing affected my relationship with death, and in turn, with life. It also made me cognizant of how all the people in my life are aging and won’t be here forever.

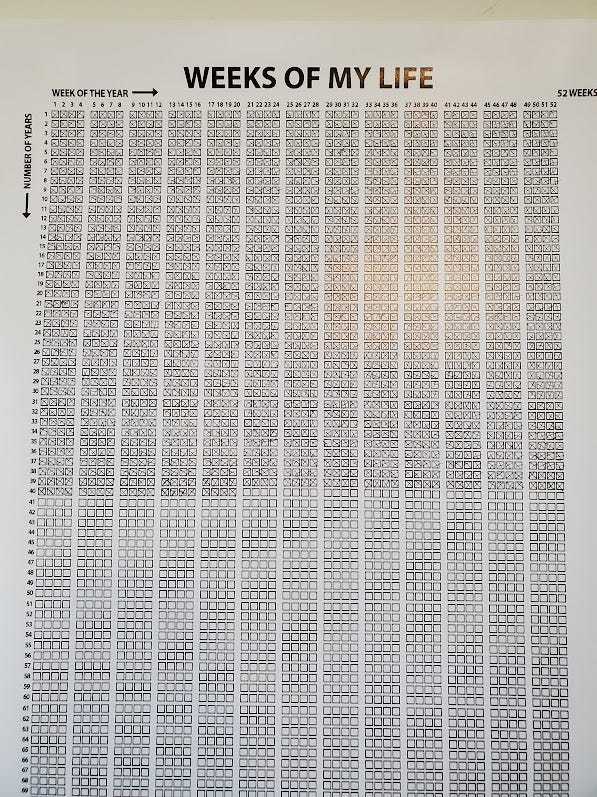

The third thing that “happened” was my deliberate decision to focus on the passage of time and on my own mortality — an awareness which I have cultivated through a variety of personal practices (one of which is the “Weeks of My Life” chart pictured above). I have prioritized this perspective for a while now, but my efforts took on a sense of heightened urgency this year.

For whatever reason, the words of Freddie Mercury and Shadal pushed an unasked question into the foreground: What is my mission in the time I have left? For Freddie, it was “making music” and being “a performer that gives the people what they want: a touch of the heavens!” For Shadal, it was “to leave to posterity a little more truth and a little less error” and “to discover new things.”

I don’t know that I’m ready to distill my goals and objectives into one or two sentences. I don’t even know whether it’s a good idea to do that, or to remain maximally open at this juncture of my personal and professional life. But I do have at least three goals I know I want to prioritize over the next year or two:

I want to write a book on Mishlei. I announced this goal publicly for the first time in my shiur entitled Rabbi Moskowitz’s Approach to Eishes Chayil. I’ve been learning Mishlei since before I converted to Judaism 23 years ago, and I’ve been teaching Mishlei ever since the beginning of my teaching career. I began recording my Mishlei shiurim just under three years ago, and I have accumulated around 450 of those recordings. But that’s not enough. I want to write a book to spread the derech ha’limud (methodology) I learned from my rebbi and developed over the years. I want to make the ideas of Mishlei accessible to the world, and I have a feeling that I am one of the few people who is in a position to do this justice. This is the most concrete of my goals.

I want to play with Torah. I wrote about this in my recent article, Octopuses, MDMA, and the Ecstasy of Torah, and I don’t have much more to say than what I said there — only that if I don’t muster up the courage to do this now, with the type of courage Freddie Mercury and Shadal displayed throughout their lives, then I’ll slip back into the old mode of worrying about what people will think, which will only waste more of what precious little time I have left.

I want to discover. Shadal’s particular mission statement really resonated with me. Not the part when he said “As long as there exists one verse in the Holy Scriptures that is not understood exactly, I must not think of defending my writings.” That’s too ambitious for someone of my limited caliber. I’m referring to the part where he said that his mission is “to discover new things.” One of my talmidim asked me a question I’ll never forget: “What is your favorite flavor of Torah?” by which he meant: “What type of Torah do you seek in everything you learn and teach? What excites you in Torah? What keeps you coming back for more?” Right away, I knew the answer: I love the process of discovering new ideas which completely transform the way I view Torah, reality, and myself, and have an impact on the way I live. It’s not even about making objectively new discoveries that haven’t been made by anyone else. It’s about making discoveries that are new to me and illuminate my mind. Bonus points if they illuminate the minds of others.

Those are the three goals that come to mind on this cool Seattle summer night. If I can keep my eye on those three goals, while remaining open to whatever Hashem has in store for me, then I think I’ll be able to say that this was time well spent.

Concluding Thoughts

Shlomo ha’Melech writes: אֶת הַכֹּל עָשָׂה יָפֶה בְעִתּוֹ גַּם אֶת הָעֹלָם נָתַן בְּלִבָּם מִבְּלִי אֲשֶׁר לֹא יִמְצָא הָאָדָם אֶת הַמַּעֲשֶׂה אֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה הָאֱלֹהִים מֵרֹאשׁ וְעַד סוֹף “[God] made everything beautiful in its time; He has also placed eternity into their hearts, that man not comprehend the work which God has made from beginning to end” (Koheles 3:11). Ibn Ezra explains: “human beings busy themselves as though they will live forever, and because of their busyness, they do not contemplate the work of God from beginning to end.”

That “busyness” is a killer. I mean that in a quasi literal sense: the busyness is what propels us through life, consuming day after day, only to realize that we’ve suddenly reached the bottom of the barrel. We would do well to read the entirety of Seneca’s On the Shortness of Life, but we’ll have to content ourselves with a single paragraph:

It is because you live as if you would live forever; the thought of human frailty never enters your head, you never notice how much of your time is already spent. You squander it as though your store were full to overflowing, when in fact the very day of which you make a present to someone or something may be your last. Like the mortal you are, you are apprehensive of everything, but your desires are unlimited as if you were immortal. Many a man will say, "After my fiftieth year I shall retire and relax; my sixtieth year will release me from obligations." And what guarantee have you that your life will be longer? Who will arrange that your program shall proceed according to plan? Are you not ashamed to reserve for yourself only the tail end of life and to allot to serious thought only such time as cannot be applied to business? How late an hour to begin to live when you must depart from life! What stupid obliviousness to mortality to postpone counsels of sanity to the fifties or sixties, with the intention of beginning life at an age few have reached!

The remedy is beautifully expressed by Oliver Burkeman in Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals (2021).

Our obsession with extracting the greatest future value out of our time blinds us to the reality that, in fact, the moment of truth is always now — that life is nothing but a succession of present moments, culminating in death, and that you’ll probably never get to a point where you feel you have things in perfect working order. And that therefore you had better stop postponing the ‘real meaning’ of your existence into the future, and throw yourself into life now.

Freddie Mercury was forced to confront this reality by his illness. Shadal (presumably) recognized it on an intellectual level long before, though I’m sure it hit him differently in his 60s than it did in his 50s, 40s, and 30s.

The best the rest of us can hope to do is to keep this truth at the forefront of our minds, using the tools given to us by the Torah and whatever other means we can muster, and reminding ourselves whenever we realize we’ve forgotten.

It’s going to take a constant fight. But we’ll keep on fighting till the end.

What would it look like for you to “become who you were born to be”? What do you feel you must do in the time you have left? And, most importantly, what is holding you back?

Like what you read? Give this article a “like” and share it with a friend! Dislike what you read? Share it anyway to spread the dislike!

Want access to my paid content without actually paying? If you successfully refer enough friends, you can get access to the paid tier for free!

Interested in reading more? Become a free subscriber, or upgrade to a paid subscription for the upcoming exclusive content!

If you've gained from what you've learned here, please consider contributing to my Patreon at www.patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss. Alternatively, if you would like to make a direct contribution to the "Rabbi Schneeweiss Torah Content Fund," my Venmo is @Matt-Schneeweiss, and my Zelle and PayPal are mattschneeweiss at gmail.com. Even a small contribution goes a long way to covering the costs of my podcasts, and will provide me with the financial freedom to produce even more Torah content for you.

If you would like to sponsor a day's or a week's worth of content, or if you are interested in enlisting my services as a teacher or tutor, you can reach me at rabbischneeweiss at gmail.com. Thank you to my listeners for listening, thank you to my readers for reading, and thank you to my supporters for supporting my efforts to make Torah ideas available and accessible to everyone.

-----

Substack: rabbischneeweiss.substack.com/

Patreon: patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss

YouTube: youtube.com/rabbischneeweiss

Instagram: instagram.com/rabbischneeweiss/

"The Stoic Jew" Podcast: thestoicjew.buzzsprout.com

"Machshavah Lab" Podcast: machshavahlab.buzzsprout.com

"The Mishlei Podcast": mishlei.buzzsprout.com

"Rambam Bekius" Podcast: rambambekius.buzzsprout.com

"The Tefilah Podcast": tefilah.buzzsprout.com

Old Blog: kolhaseridim.blogspot.com/

WhatsApp Group: https://chat.whatsapp.com/GEB1EPIAarsELfHWuI2k0H

Amazon Wishlist: amazon.com/hz/wishlist/ls/Y72CSP86S24W?ref_=wl_sharel

I really love this paragraph:

"For me, these past three years (post-Shalhevet, a”h) have been about fulfilling Dolly Parton’s injunction, “Find out who you are and do it on purpose.” I honestly can’t tell whether I’m still in the exploratory phase of that journey, or whether I’m in the implementation phase, or whether the two are the same, or whether they’re different but there’s no real way to tell the difference, or whether I’m misguided in my attempt to even try to discern the difference. All I know is that I’m on the right track. Or at least, I try to be on the right track, and I right myself whenever I realize I’ve veered. That is the most I can do."

I feel like I've had a similar experience over these past three years. For me, it has been coming to terms with the fact that I don't think my sole purpose in life is to gain as much knowledge as possible, or "perfecting my intellect," be it in Torah or secular topics, and instead balancing that with my family and my role in endodontics.

You are the champion, my friend! Thanks first of all for appreciating my Shadal translations and research. Second, gotta love those graphics. And third, your theme resonates with me, especially since I have about 30 years on you. Not surprisingly, I have begun to lose some good friends, too. As for my main goal in life (other than to love and enjoy my family), it's always been clear to me that this consists of bringing as many of Shadal's Hebrew and Italian writings as I can to the attention of the English-speaking public. Luckily, I've already been at this, on and off, for most of my adult life, and I pray for ample time to keep going. Shekoyach, Matt, and best of luck with all your goals as well.