Leo Tolstoy, Eishes Chayil, and Caring What Others Think

This week's Torah content has been sponsored by Naomi Mann in honor of Rabbi Moskowitz zt"l, whose shloshim is this week.

Click here for a printer-friendly version of this article, and click here for an audio version.

Leo Tolstoy, Eishes Chayil, and Caring What Others Think

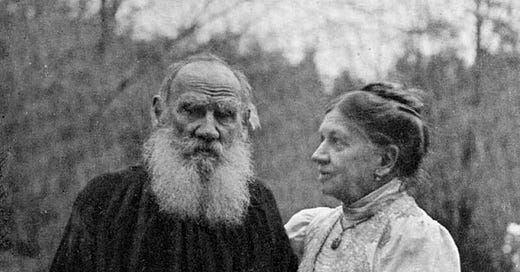

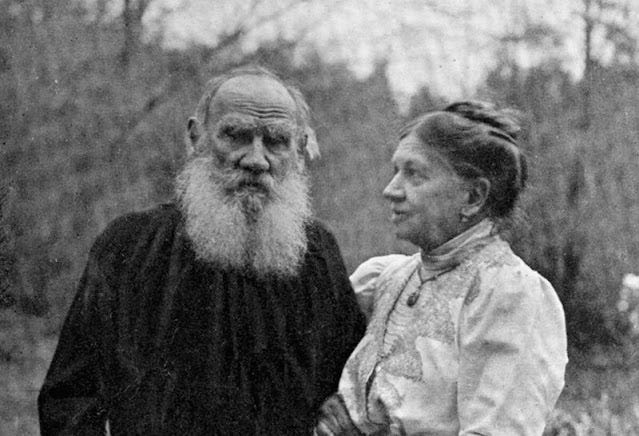

The following quotation is attributed to Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy: "If you care too much about being praised, in the end you will not accomplish anything serious ... Let the judgments of others be the consequence of your deeds, not their purpose.” This advice bears a striking resemblance to the final pasuk of Eishes Chayil at the conclusion of Sefer Mishlei. Here is that pasuk in context:

Her children arise and laud her; her husband, and he praises her, [saying]: “Many daughters have been successful, but you surpass them all.” Popularity is false and beauty is fleeting, but a woman who fears Hashem, she should be praised. Give her of the fruit of her hands, and let her actions praise her in the gates. (Mishlei 31:28-31)

Shlomo ha’Melech’s “give her of the fruit of her hands, and let her actions praise her in the gates” corresponds precisely to Tolstoy’s “Let the judgments of others be the consequence of your deeds.”

There are people who are obsessed with what others think. These are the people who, in Tolstoy’s words, “Let the judgments of others be … their purpose.” These are the same people whom Shlomo ha’Melech warns about the falsehood of popularity and the temporary nature of beauty. There are other people who have reached such a high level that they don’t care at all what people think. They are the ones whom the Rambam characterizes as “serving Hashem out of love,” who “act in line with truth because it is true” (Rambam, Laws of Teshuvah 10:2). They are neither elated by praise nor are they distraught by disapproval.

Tolstoy and Shlomo are both allowing their audience to care about what people think, provided they do so in a healthier way. This is why Tolstoy warns against “[caring] too much about being praised,” and permits his audience to attend to the judgments of others, as long as those judgments aren’t the purpose of their actions. Likewise, Shlomo is talking to a woman who values praise, and whose children and husband regularly praise her. He merely warns her not to fall for the criteria of praise held by most women, but instead, to value being praised as God-fearing (i.e. one who acts based on wisdom), allowing the long-term benefits of her actions to speak for themselves rather than clamoring for approbation in the present.

This is a realistic approach. Caring too much about praise is guaranteed to end in disaster but attempting to quit one’s addiction to praise “cold turkey” is equally foolhardy. As social animals, we are hardwired to care what others think. Any attempt to override this by sheer force of will is bound to backfire. The transition to lishmah (doing what is good for its own sake) must come about gradually and organically. The trick is to find middle-ground strategies to facilitate that transition. Another excellent example of this can be seen in the words of Socrates to his student, Crito, who was concerned with his own reputation:

But why, my dear Crito, should we care about the opinion of the many? … We must not regard what the many say of us: but what he, the one man who has understanding of just and unjust, will say, and what the truth will say. And therefore you begin in error when you advise that we should regard the opinion of the many about just and unjust, good and evil, honorable and dishonorable.

Socrates doesn’t tell Crito, “You shouldn’t care what anyone thinks!” nor does he say, “Just do what’s right and ignore everything else!” Instead, he invites Crito to imagine truth, goodness, and justice in the form of an actual person’s opinion – a “man who has understanding of just and unjust” – and urges him to care about what that person would say. The Torah accomplishes the same thing by personifying Hashem and urging us to care about how we appear in His eyes rather than in the eyes of man. Such is the way of Torah: not to quash the yetzer ha’ra (evil inclination), but to channel it and direct it towards a higher end.

___________________________________________________________________________________

If you've gained from what you've learned here, please consider contributing to my Patreon at www.patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss. Alternatively, if you would like to make a direct contribution to the "Rabbi Schneeweiss Torah Content Fund," my Venmo is @Matt-Schneeweiss, and my Zelle and PayPal are mattschneeweiss at gmail.com. Even a small contribution goes a long way to covering the costs of my podcasts, and will provide me with the financial freedom to produce even more Torah content for you.

If you would like to sponsor a day's or a week's worth of content, or if you are interested in enlisting my services as a teacher or tutor, you can reach me at rabbischneeweiss at gmail.com. Thank you to my listeners for listening, thank you to my readers for reading, and thank you to my supporters for supporting my efforts to make Torah ideas available and accessible to everyone.

Be sure to check out my YouTube channel and my podcasts: "The Mishlei Podcast", "The Stoic Jew" Podcast, "Rambam Bekius" Podcast, "Machshavah Lab" Podcast, "The Tefilah Podcast"