Mishlei 17:13 - Mishleic Karma

"Karma" isn't a Jewish belief, but we certainly maintain that what goes around comes around, albeit in a Mishleic way.

Click here for a printer-friendly version of this article.

Mishlei 17:13 - Mishleic Karma

משלי יז:יג

מֵשִׁיב רָעָה תַּחַת טוֹבָה, לֹא תָמוּשׁ רָעָה מִבֵּיתוֹ

Mishlei 17:13

If one repays good with bad, badness will not depart from his house.

The questions on this pasuk are:

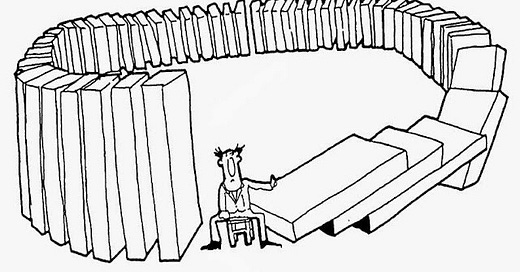

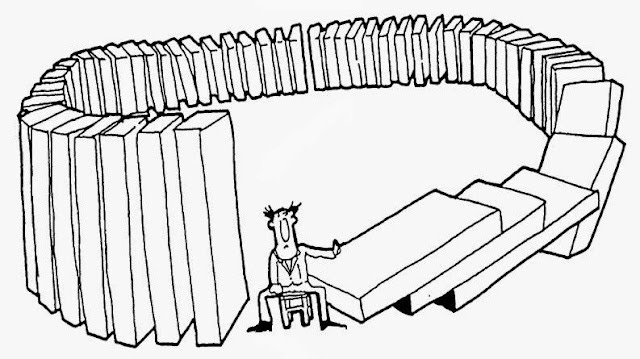

How does this work? Our pasuk appears to be describing a karma-like effect. The problem is that karma - in the sense of "a mystical force of retribution" - isn't real. Since Mishlei deals with consequences within the laws of nature, how can we understand the phenomenon in our pasuk?

What "badness" will not depart from his house? The term "badness" (raah) is as vague as can be. Is this the same type of "badness" as the "bad" in the first half of the pasuk? If not, what is it? And why was Shlomo ha'Melech so vague?

What does it mean when it says that the badness "will not depart from his house"? Why focus on the house instead of the person himself? And what are the implications of "will not depart"? This would seem to indicate that the "badness" was always there, and could have departed were it not for this guy's repaying of good with bad.

[Time to think! Read on when ready.]

Here is my four-sentence summary (with an extremely liberal definition of "sentence") of the main idea of this pasuk:

It is human nature to expect that the beneficiaries of good actions will (or should) repay these actions with good; consequently, the person who repays good with bad will be universally abhorred. Such an individual is exceedingly egotistical in that he believes he is entitled to be the recipient of good from others, but at the same time, feels that he doesn’t owe them anything; not only that, but he feels free to treat them however he pleases, as though they are nothing but his pawns who exist only to serve him. As a direct consequence of this insensitive, egocentric way of relating to others, the “house” (i.e. system) of such an individual will be continually “plagued by badness” in four ways: (1) the members of his household/system will resent him, and that resentment will yield harmful consequences; (2) they will not be willing to do good for him, and he will miss out on those benefits; (3) his sense of entitlement will cause him to be remiss in his responsibilities towards the members of his household/system; this will harm the household/system as a whole, and he – as a part of that household/system – will suffer as a consequence; (4) his egotism will generate excessive and unrealistic expectations of how others should relate to him, and these unfulfilled expectations will breed perpetual frustration, dissatisfaction, and anger. Although there is no such thing as actual Karma, the victim of this type of evil recompense can take solace in his knowledge of “Mishleic karma” and know with certainty that the perpetrator will suffer greatly as a “punishment” for the way he treats others.

This is an example of what I call a "list-pasuk." Many pesukim in Mishlei state a specific consequence for a specific behavior. In contrast, "list-pesukim" simply identify the behavior of the fool/rasha and leave it to the reader to figure out the consequences, of which there are many. "List-pesukim," such as our pasuk, will typically make general reference to the consequences in vague or categorical terms, so as not to lead the reader to focus on a narrow set of consequences.

The phenomenon of "list-pesukim" exemplifies one of the many differences between Shlomo ha'Melech's proverbs and (for lack of a better term) "English proverbs." English proverbs are essentially spoon-fed truths which are instantly understandable: "the early bird catches the worm," "no pain no gain," "a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush." In contrast, the vast majority of Shlomo ha'Melech's proverbs are not readily understandable; their ideas can only be accessed after thought and analysis.

I believe that the main reason for this is because Shlomo ha'Melech is trying to do more than just deliver content. His goal is for his students to train their minds and acquire a different way of thinking about life. By stating these ideas in cryptic language, he forces the student to explore the subject matter of each pasuk in-depth and try out different ways of learning. In the end, the students gains more from the analysis of the pasuk than a single idea.

"List-pesukim" fit into this paradigm because there isn't even a specific idea that he's conveying. Instead, these pesukim are like Shlomo pointing to a certain behavior and saying, "Hey - check that guy out. What do you think is going to happen to him? What mistake(s) is he making?" The "lesson" of the pasuk ultimately comes from the student's own analysis, with zero spoon-feeding.

Let me know what you think of my explanation of the pasuk. I’d love to hear your interpretation as well!

Like what you read? Give this article a “like” and share it with someone who might appreciate it!

Want access to my paid content without actually paying? If you successfully refer enough friends, you can get access to the paid tier for free!

Interested in reading more? Become a free subscriber, or upgrade to a paid subscription for the upcoming exclusive content!

If you've gained from what you've learned here, please consider contributing to my Patreon at www.patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss. Alternatively, if you would like to make a direct contribution to the "Rabbi Schneeweiss Torah Content Fund," my Venmo is @Matt-Schneeweiss, and my Zelle and PayPal are mattschneeweiss at gmail. Even a small contribution goes a long way to covering the costs of my podcasts, and will provide me with the financial freedom to produce even more Torah content for you.

If you would like to sponsor a day's or a week's worth of content, or if you are interested in enlisting my services as a teacher or tutor. Thank you to my listeners for listening, thank you to my readers for reading, and thank you to my supporters for supporting my efforts to make Torah ideas available and accessible to everyone.

-----

Substack: rabbischneeweiss.substack.com/

Patreon: patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss

YouTube: youtube.com/rabbischneeweiss

Instagram: instagram.com/rabbischneeweiss/

"The Stoic Jew" Podcast: thestoicjew.buzzsprout.com

"Machshavah Lab" Podcast: machshavahlab.buzzsprout.com

"The Mishlei Podcast": mishlei.buzzsprout.com

"Rambam Bekius" Podcast: rambambekius.buzzsprout.com

"The Tefilah Podcast": tefilah.buzzsprout.com

Old Blog: kolhaseridim.blogspot.com/

WhatsApp Content Hub (where I post all my content and announce my public classes): https://chat.whatsapp.com/GEB1EPIAarsELfHWuI2k0H

Amazon Wishlist: amazon.com/hz/wishlist/ls/Y72CSP86S24W?ref_=wl_sharel