Mishlei 29:9 - The Fool's Dirty Debate Tactics

Click here for a printer-friendly version of this blog post.

Artwork: Browbeat, by Chris Rahn

Mishlei 29:9 - The Fool's Dirty Debate Tactics

משלי כט:ט

אִישׁ חָכָם נִשְׁפָּט אֶת אִישׁ אֱוִיל וְרָגַז וְשָׂחַק וְאֵין נָחַת:

Mishlei 29:9

Raw Translation: A wise man who nishpat with a foolish man, and he rages and he laughs, and there is no satisfaction/rest.

I chose this pasuk for today's Mishlei post because it's a good example of how ambiguity in the wording can lead to multiple directions in the analysis. When I learned this pasuk with my Mishlei group this past Shabbos, we didn't have access to my mikraos gedolos (compendium of commentaries), and we were forced to work out the translation on our own. I'll include the difficulties in my list of questions on the pasuk:

(1) What does "nishpat" mean? The root SH.F.T. (ש.פ.ט.) typically denotes "to judge," but can also mean "to dispute" or "to argue." The use of the nifal (passive) form is also very strange. "is judged" makes sense, but "is disputed" or "is argued [with]" are also valid translations.

(2) Who "rages" and "laughs"? Is the chacham (wise man) raging and laughing at the eveel (foolish man), or is the eveel raging and laughing at the chacham?

(3) What, exactly, is this "rage" and "laughter"? Is "rage" different than mere "anger"? Is the emphasis on his feeling of anger, or on his display of anger? The laughter is even vaguer than the rage. Is this talking about "laughter" that stems from humor? Is it laughter of mockery? Is it laughter of happiness and camaraderie? And why is this person raging and laughing? What is the relationship between the situation (i.e. arguing, disputing, or being judged) and these two reactions? Is it davka (specifically) these two reactions, or are these just examples from within a larger category?

(4) Who doesn't receive satisfaction - and why not? The answer to this question is dependent on the answer to Question #2, and maybe dependent on the answer to Question #3.

[Time to stop and think about the pasuk in light of these questions. Read on when ready.]

Before we can present the main idea of the pasuk, we need to settle on a translation. Here are the approaches taken by the various meforshim:

Rashi: A wise man who argues with a foolish man may rage and laugh, but there will be no satisfaction [for the wise man].

Ralbag: When a wise man argues with a foolish man, [the fool] will rage and laugh, and there will be no rest [for the wise man].

Ibn Ezra: When a wise man is judged with a foolish man, [the fool] may rage and laugh, but there will be no satisfaction [for the wise man].

Metzudas David: A wise man who is judged with a foolish man may rage and laugh, but there will be no satisfaction [for the wise man].

As I mentioned, we didn't have access to meforshim when we learned this pasuk. The translation we came up with happens to be one that none of the meforshim explicitly say:

Our Translation: When a wise man is judged with a foolish man, [the fool] may rage and laugh, but he will have no satisfaction.

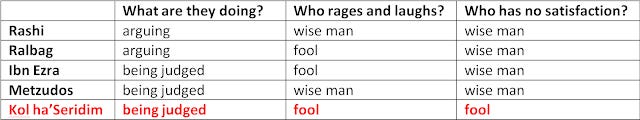

For those of you who appreciate charts, here are the five translations side by side:

The fact that none of the meforshim proposed this translation doesn't bother me. I am not aware of any grammatical or syntactical problems, and our translation reflects the most straightforward reading, both in terms of the use of the passive "nishpat" (which literally means "he is judged") and in the conservative reading of the ambiguous pronouns (i.e. "the fool may rage and laugh, but there will be no satisfaction for the fool"). Plus, "raging" and "laughing" seem more like the actions of an eveel than the actions of a chacham, which is why we shied away from translating the pasuk like Rashi and Metzudas David.

Here is my four-sentence summary of the main idea:

When a chacham finds himself in a situation in which he is being judged alongside an eveel (e.g. two participants in a public debate, two businessmen competing for the same customers, two candidates vying for the same position), he should prepare himself to face the dirty tactics that the eveel will use. The fool will attempt to prevail by utilizing provocatively aggressive displays of emotion – such as rage and mocking laughter – in an effort to destabilize the chacham, and to make himself appear dominant in comparison. As long as the chacham remains visibly unshaken and unperturbed by the eveel's bombastic onslaught, and doesn’t give him the satisfaction of pushing his buttons, then these tactics will backfire. The audience (i.e. whoever is in a position to pass judgment) will observe the stark contrast between the chacham’s cool, levelheaded, objective disposition and the eveel’s heated, combative, immature bullying; this side-by-side comparison will simultaneously boost the ethos of the chacham and diminish that of the eveel. Chances are that the eveel, himself, will become frustrated with the chacham’s indifference to his assaults, which will destabilize him, making him feel even more frantic and less in control of himself; this, in turn, will make him appear desperate and pathetic in the eyes of the audience, thereby giving the chacham an edge - in addition to the substance of his arguments, which will inevitably be superior to the eveel's.

After we came up with this explanation, and I gained access to my meforshim, I saw that the Ri Nachmias gives a very similar explanation of our pasuk. The only difference is that he translates "nishpat" as "argues" instead of "is judged," like Rashi and Ralbag, in contrast to Ibn Ezra and Metzudas David. Nevertheless, he also learns - like we do - that there is an audience present in the situation, which practically means that the chacham and eveel are being judged. Here is the relevant excerpt from the Ri Nachmias's (much lengthier) explanation:

If a wise man who argues with a fool, [the fool] may rage and laugh ... Since this fool doesn't have much knowledge, he'll project self-images (oseh tzuros me'atzmo) to deceive the people who are there ... These are polemical techniques (darchei nitzuach) which [the eveel uses to] trick listeners [into thinking that he] knows what he doesn't [actually know].

The Ri Niachmias quotes a pasuk from elsewhere in Shlomo ha'Melech's writings which supports our interpretation: "The words of the wise are heard calmness (b'nachas) over the shouting of a ruler among fools" (Koheles 9:17). In the Rambam's description of how talmidei chachamim (Torah scholars) speak and behave, he borrows this phrase from Koheles:

A talmid chachamim shouldn't yell or shout when he speaks, like animals and wild beasts, nor should he raise his voice; rather, his speech with people should be calm. And when he speaks calmly, he should be careful not to distance himself, to the extent that he appears haughty.

In other words, this calmness in speech shouldn't be limited to situations involving a fool. Rather, "nachas" (in the sense of "calmness" rather than "satisfaction") should be the default mode of speech for talmidei chachamim.

The Ralbag would agree with the title of this post, but according to him, our pasuk focuses on a specific tactic used by the eveel in debates: interrupting the chacham. He translates our pasuk as: "When a wise man argues with a foolish man, [the fool] will rage and laugh, and there will be no rest [for the wise man]." Here is his explanation:

When a wise man argues with a foolish man, in a verbal back-and-forth, the eveel will not allow the chacham to speak and to finish his statements. Instead, sometimes he'll react angrily to what he hears the chacham say and will not allow him to complete his statements, and sometimes he'll laugh and mock what he hears [the chacham] say, and he will not give him a pause (nachas) which would enable him to complete what he intended to clarify. This pasuk is, as it were, a warning to the chacham not to argue with an eveel.

One of the best examples of our pasuk in action is the Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson. I found a video which exemplifies all three interpretations - that of the Ralbag, the Ri Nachmias, and ours. I wanted to find a shorter video, but this is the best I could come up with.

It will not always be possible for a chacham to avoid debating with or being judged alongside an eveel. When such a situation arises, the chacham must keep the eveel's repertoire of tricks at the forefront of his mind, and not allow him to get the upper hand.