Parashas Behaalosecha: Trumpets, Shofar, and Rosh ha'Shanah

This post stands on its own, but can also be viewed as a sequel to Parashas Behaalosecha: The Non-Symbolic Trumpets.

Click here for a printer-friendly version of this blog post.

Parashas Behaalosecha: The Trumpets and the Shofar

This week's parashah introduces the mitzvah of the chatzotzros (trumpets). These chatzotzros served a number of functions: some of which were limited to Bnei Yisrael's sojourn in the Wilderness, and others which are part of Taryag (the 613 mitzvos) and are in effect for all generations. In this blog post we will focus on the role of the chatzotzros during an eis tzarah (time of trouble).

The pesukim state:

Hashem spoke to Moshe, saying: "Make for yourself two silver trumpets - make them hammered out ... The sons of Aharon, the Kohanim, shall sound the trumpets, and it shall be for you an eternal decree for your generations. When you go to wage war in your Land against an enemy who oppresses you, you shall sound short blasts of the trumpets, and you shall be remembered before Hashem, your God, and you shall be saved from your enemies. On a day of your gladness, and on your festivals, and on your new moons, you shall sound the trumpets over your burnt-offerings, and over your feast peace-offerings; and they shall be a remembrance for you before your God; I am Hashem, your God. (Bamidbar 10:1-10)

The Rambam [1] codifies this use of the chatzotros at the beginning of Hilchos Taaniyos (the Laws of Fasts) as a component part of the mitzvah of zaakah b'eis tzarah (crying out to Hashem during a time of trouble). He writes:

1:1 - It is a positive mitzvah of the Torah to cry out and to sound the trumpets on every tzarah that befalls the community, as it is stated, “[When you go to wage war in your Land] against an enemy who oppresses you, you shall sound short blasts of the trumpets, [and you shall be remembered before Hashem, your God, and you shall be saved from your enemies]" (Bamidbar 10:9), meaning to say: anything that afflicts you - such as drought, epidemic, locusts, and the like - cry out on them and sound [the trumpets].

1:2 - This principle is one of the darchei teshuvah (ways of repentance), that at a time of the onset of an affliction, and [people] cry out and sound the trumpets, everyone will know that it was because of their evil conduct that this bad occurrence befell them, as it is written, “Your iniquities have turned away these things [to you], and your sins have withheld good from you” (Yirmiyahu 5:25), and this will cause them to remove the affliction from upon them.

1:3 - But if they do not cry out and do not sound the trumpets, but instead say, “This is a natural event which befell us, and this affliction is a chance occurrence” - behold, this is a derech achzarius (way of cruelty), and will cause them to cling to their evil conduct, and [this] affliction and others will increase. This is what is written in the Torah, “[And if, with this, you do not listen to Me,] and you walk with me with chance, then I will walk with you in the fury of chance, [and I will also chastise you, seven times for your sins]” (Vayikra 26:26-28), meaning to say, when I bring an affliction upon you to cause you to do teshuvah, if you say that it is chance, then I will increase upon you the fury of that “chance.”

It is clear from the Rambam's presentation that the mitzvah of chatzotzros and the mitzvah of zaakah b'eis tzarah are intertwined. The question is: What is the relationship between these two mitzvos? Why does the Torah command us to sound the trumpets and cry out in prayer at a time of affliction?

The Ralbag [2] answers this question:

Whenever a catastrophe befalls the Jewish people, the Kohanim should sound a teruah ("crying" blast) on the trumpets ... and through this action, they will be remembered before Hashem ... for this action causes their hearts to be broken and crushed, that they may return to Hashem, so that He will have mercy on them when they pray to Him, for tefilah together with this teruah will cause them to be "remembered" for the reason we mentioned, because the frightening sound will cause people's hearts to tremble, as it is stated, "If a shofar is sounded in the city, will the people not tremble?" (Amos 3:6). Through this, their tefilah and their teshuvah will be complete. [3]

Like the Sefer ha'Chinuch, the Ralbag understands that the Torah chose chatzotzros for their impact on the human psyche. The clarion call of the chatzotzros may be compared to a tornado siren - a loud sound designed to trigger the emotional response of: "DANGER! DANGER! TAKE PRECAUTION NOW!" - but instead of propelling us to take physical precaution, the alarm sound of the chatzotzros prompts us to take spiritual precaution, through tefilah and teshuvah.

It is interesting to note that the particular blasts that were sounded on the chatzotzros during an eis tzarah - namely, a teruah ("crying" sound) bracketed by a tekiah ("simple" blast) on each side - are the same blasts that are sounded with the shofar on Rosh ha'Shanah. This is not a coincidence. In fact, in each case, when the full mitzvah is performed in the Beis ha'Mikdash (the Holy Temple), the Kohanim sound both instruments simultaneously, in a manner that highlights which of the two mitzvos is being performed.

With regards to the teruah of the chatzotzros at an eis tzarah (time of trouble) the Rambam [4] writes:

During these days of fasting [over a tzarah that befalls the community] we cry out with tefilah and supplications and we sound the chatzotros alone. But in the Mikdash we sound the chatzotzros and the shofar: the shofar [blast] is cut short, and the [blast of] the chatzotros is prolonged, since the mitzvah of the day is with the chatzotzros.

And with regards to the teruah of the shofar on Rosh ha'Shanah the Rambam [5] writes:

In the Mikdash one shofar would sound with the two chatzotzros on the sides: the shofar [blasts] would be prolonged, and the [blast of the] chatzotzros would be cut short, since the mitzvah of the day is with the shofar.

This raises the question: What is the relationship between the teruah of chatzotzros at an eis tzarah and the teruah of the shofar on Rosh ha'Shanah?

The Ralbag offers a straightforward answer, based on his explanation of chatzotzros:

We have seen that according to the Torah, complete teshuvah and kaparah (atonement) follows after inui ("affliction" i.e. fasting) and teruah. It is for this reason that Hashem desired that the kaparah on the 10th of the Seventh Month (i.e. Yom ha'Kippurim) should be preceded by a teruah on Rosh Chodesh [of that month] (i.e. Rosh ha'Shanah), in order to subdue the hearts [of Bnei Yisrael] from [the recognition] of their sins so that they will do complete teshuvah to Hashem. Then, at the end of this process, they will afflict their souls (i.e. fast) on the 10th day. Thus, this is another instance of the pairing of teruah with fasting.

The answer given by the Ralbag is astounding in its elegance: the teruah of the shofar on Rosh ha'Shanah is a special case of teruah b'eis tzarah.

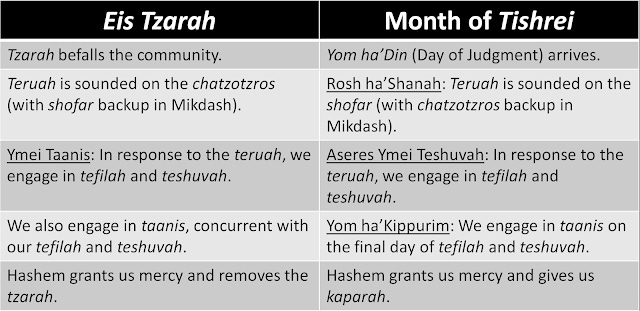

In other words, the beginning of Tishrei is the Yom ha'Din (Day of Judgment) - the period during which all human beings are judged for their deeds. This is an eis tzarah, in that our fate hangs in the balance. At the onset this eis tzarah, we sound a teruah as a alarm, calling us to take action. Unlike the standard eis tzarah of an imminent physical threat, in which Beis Din declares Ymei Taanis (Days of Fasting) and we engage in tefilah, teshuvah, and taanis until the affliction ends, the eis tzarah of Yom ha'Din has a predefined terminus: Yom ha'Kippurim, when our verdict is sealed. Accordingly, we engage in tefilah and teshuvah throughout the Aseres Ymei Teshuvah (Ten Days of Repentance), but we postpone the taanis until Yom ha'Kippurim - the final day of teshuvah on which we beseech Hashem for kaparah.

Here is a chart to illustrate the parallels:

Parallels between eis tzarah and Tishrei according to the Ralbag.

The Ralbag [6] is so committed to this theory of the month of Tishrei that in his commentary of Rosh ha'Shanah in Parashas Emor, he doesn't even make explicit reference to the fact that Rosh ha'Shanah is a Yom Tov; he merely frames it as a day of shofar-sounding on the Rosh Chodesh preceding Yom ha'Kippurim:

"In the seventh month, on the first of the month, there shall be a rest day for you, a remembrance with shofar blasts" (Vayikra 23:24). From this it is clear that the teruah on "an enemy who oppresses you" (Bamidbar 10:9) should be followed by inui nefesh ("affliction of the soul" i.e. fasting), for this is its purpose. Since Yom ha'Kippurim is on the 10th of this month ... [the Torah] prepares people by arousing them to do teshuvah and breaking and subduing their hearts starting with Rosh Chodesh of this month (i.e. Rosh ha'Shanah). It is clear that the shofar blast instills trepidation in the heart, as it is stated, "If a shofar is sounded in the city, will the people not tremble?" (Amos 3:6). In general, loud sounds are very terrifying, and serve as an means of subduing the nefesh ha'bahamis (animalistic psyche). It is as if [through shofar] we are being awakened to subdue our hearts and analyze our deeds to correct what is crooked therein, in order that we should be ready for the kaparah on Yom ha'Kippurim.

On a more personal note, I have found this explanation of the Ralbag to be extremely helpful my own experience of the Yomim Noraim (Days of Awe). According to the Ralbag, shofar isn't a phenomenon of Rosh ha'Shanah. Rather, it is a phenomenon of eis tzarah which has a special expression during the Aseres Ymei Teshuvah.

By framing the Aseres Ymei Teshuvah as an eis tzarah, modeled after the eis tzarah of a physical danger, the teruah of the shofar on Rosh ha'Shanah carries a more powerful meaning for me than it did when I viewed it as its own isolated institution.

[1] Rabbeinu Moshe ben Maimon (Rambam / Maimonides), Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zmanim, Hilchos Taaniyos 1:1-3

[2] Rabbeinu Levi ben Gershom (Ralbag / Gersonides), Commentary on Sefer Bamidbar 10:9

[3] Ralbag also addresses the question of why the Torah doesn't explicitly mention the tefilah and teshuvah which accompany the chatzotzros. He writes:

The Torah was silent here regarding the teshuvah and tefilah because it already stated as a condition, "and you shall be remembered [before Hashem]" which means to say: "do this in a way that will cause you to be remembered" - and this is through teshuvah and tefilah, which cause the divine hashgachah (providence) to extend to them.

[4] Rabbeinu Moshe ben Maimon (Rambam / Maimonides), Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zmanim, Hilchos Taaniyos 1:4

[5] ibid. Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zmanim, Hilchos Shofar v'Sukkah v'Lulav 1:2

[6] Rabbeinu Levi ben Gershom (Ralbag / Gersonides), Commentary on Sefer Vayikra 23:24