Parashas Chukas: Overlooking Sacrilegious Speech

Click here for a printer-friendly version of this article, and click here for an audiobook version.

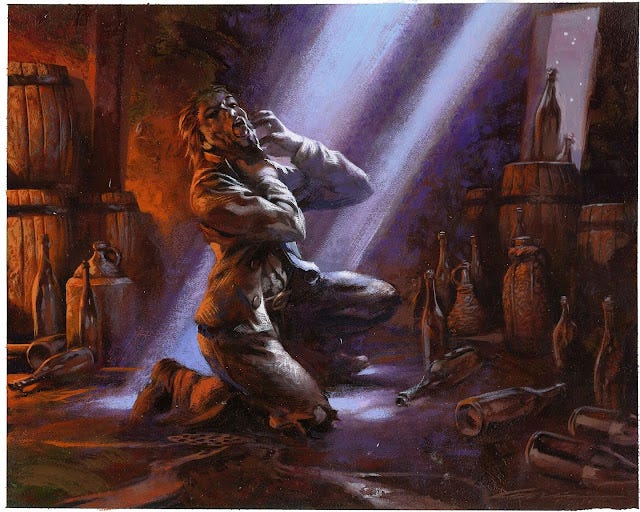

Artwork: Curse of Thirst, by Christopher Moeller

Parashas Chukas: Overlooking Sacrilegious Speech

To anyone who has read through Sefer Shemos and Sefer Bamidbar, it is apparent that Bnei Yisrael complain. A lot. On the surface, their complaints in this week's parashah seem to be harsh - not harsher than usual, but harsh nonetheless:

The Children of Israel, the whole assembly, arrived at the Wilderness of Tzin in the first month and the people settled in Kadesh. Miriam died there and she was buried there. There was no water for the assembly, and they gathered against Moshe and Aharon. The people quarreled with Moshe and spoke up, saying, "If only we had perished as our brethren perished before Hashem! Why have you brought the congregation of Hashem to this wilderness to die there, we and our animals? And why did you bring us up from Egypt to bring us to this evil place? - not a place of seed, or fig, or grape, or pomegranate; and there is no water to drink!" (Bamidbar 20:1-5)

Sounds pretty bad, right? Not only do these statements reflect Bnei Yisrael's lack of bitachon (trust) and lack of hakaras ha'tov (gratitude), but they actually go so far as to accuse Moshe Rabbeinu of redeeming them from Egypt in order to kill them in the desert!

One would expect Hashem to respond with a harsh punishment, as He has in many other cases, and to chastise them for speaking disparagingly about His greatest servant. After all, we saw what happened to Miriam when she said even the most slightly wrong thing about Moshe.

The astounding thing is that Bnei Yisrael aren't punished. In fact, they are given exactly what they ask for, without any indication of Divine wrath:

Hashem spoke to Moshe, saying, "Take the staff and gather together the assembly, you and Aharon your brother, and speak to the rock before their eyes that it shall give its waters. You shall bring forth for them water from the rock and give drink to the assembly and to their animals" (ibid. 20:7-8).

The question is: Why didn't Hashem punish them? What makes this instance of complaining different from the other cases in which Bnei Yisrael were punished?

The Ralbag [1] answers in his summary of the toalos (lessons) we learn from the parashah:

The first lesson we learn [in this section is] in middos (character traits), namely, that it is not proper to excessively denigrate a person who makes inappropriate statements at a time of suffering and lack of strength. We see that when Israel suffered greatly because of thirst, and they were afraid they would die because of the severity of their thirst, they said harsh words against Moshe - and yet, we do not find that they were punished for this. Indeed, Hashem (exalted is He) gave them water.

According to the Ralbag, Hashem didn't punish Bnei Yisrael for their otherwise inappropriate statements because they were in a state of extreme suffering. In contrast, Bnei Yisrael's other complaints were not out of genuine distress. For example, the first time Bnei Yisrael complained about water, the pesukim make it clear that they were doing so in a quarrelsome manner, in order to test Hashem:

"The entire assembly of the Children of Israel journeyed from the Wilderness of Sin to their journeys, according to the word of Hashem. They encamped in Rephidim and there was no water for the people to drink. The people quarreled with Moshe and they said, 'Give us water that we may drink!' Moshe said to them, 'Why do you quarrel with me? Why do you test Hashem?'" (Shemos 17:1-3).

Another example is the first time Bnei Yisrael complain in Sefer Bamidbar the Torah says: "The people acted as complainers; it was evil in the ears of Hashem" (Bamidbar 11:1). The meforshim (commentators) explain that they weren't genuinely complaining out of any real need; rather, they were "acting like complainers" in order to test Hashem, or to rebel against Him. [2]

Similarly, in the very next episode: "The mixed multitude that was among them cultivated a craving, and the Children of Israel also wept once more, and said, "Who will feed us meat?" The meforshim explain that the people initially didn't feel the need for meat. It was only when the mixed multitude awakened their desire that they complained to Hashem.

In all three of these cases, Hashem did not tolerate their inappropriate speech. Punishment was swift and unequivocal. Why? Because in none of these cases did Bnei Yisrael's complaining stem from any genuine need or state of distress.

It is important to note that the Ralbag categorizes this lesson as a lesson in middos (character traits) rather than a lesson in deos (knowledge of how Hashem operates). In other words, Hashem's willingness to overlook Bnei Yisrael's inappropriate speech should not be regarded "merely" as some abstract principle of metaphysics. Rather, it should be looked upon as one of Hashem's middos ha'rachamim (merciful modes of behavior), which we are commanded to emulate. [3]

Whenever one comes across a lesson in middos, it is useful to think about specific ways in which it can be implemented in one's own life. As a high school teacher, I am often confronted by complaining teenagers. They complain about everything under the sun: homework, tests, school rules, teachers, administrators, field trips, student activities, parents, the weather, the temperature, Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton, Judaism, Jews, non-Jews ... the list goes on. Sometimes their negative remarks cross the border into the "inappropriate" or even the "prohibited" category.

As was the case with Bnei Yisrael, most of my students' complaints are out of line. However, after reading this Ralbag, I realize that sometimes - on rare occasion - my students' negative remarks do come from a place of genuine pain, distress, or unjust treatment. When this happens, I am sometimes quick to lump these complaints into the general category of unwarranted teenage complaining. But I now realize that if I am to emulate the middos ha'Kadosh Baruch Hu, I should really take the care to discern the nature of their complaint. I must at least make the effort to see past the words they are saying and try to understand where these words are coming from. And if they are coming from a state of real suffering, then it might be correct to respond with merciful tolerance, as Hashem did with Bnei Yisrael.

In highlighting this lesson in middos the Ralbag is reminding us of a derech in learning ethics from Chumash. Whenever we find ourselves confronted with a situation in which Hashem acts differently than the way we would be inclined to act, we must investigate the situation and strive to understand the wisdom and mercy in Hashem's approach, so that we may learn lessons from His conduct which we can apply to our own lives.

[1] Rabbeinu Levi ben Gershom (Ralbag / Gersonides), Commentary on Sefer Bamidbar, end of Parashas Chukas

[2] see Rabbeinu Shlomo ben Yitzchak (Rashi) and Rabbeinu Ovadiah Sforno on Bamibdar 11:1

[3] see Rabbeinu Moshe ben Maimon (Rambam / Maimonides), Mishneh Torah: Sefer ha'Mada - Hilchos Deos Chapter 1