Tetzaveh: Philosophical Pants

The most underappreciated item of the bigdei kehunah (priestly vestments) is the undergarments. In this article, we analyze these "philosophical pants" and uncover the many Torah ideas they embody.

The Torah content for this week has been sponsored by Rifka Kaplan-Peck in tribute to the Bibas family. May Hashem avenge their blood and may He grant Yarden Bibas and the extended family comfort in the love of Am Yisroel who mourn with them.

Click here for a printer-friendly version of this article.

Tetzaveh: Philosophical Pants

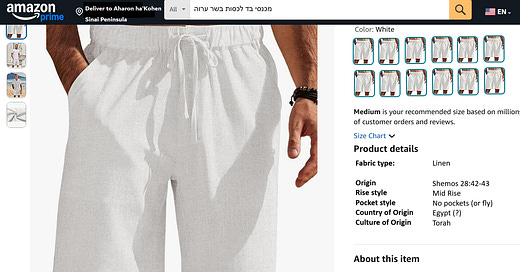

Nearly all the bigdei kehunah (priestly vestments) contribute to the “glory and splendor” (Shemos 28:2) of the kohanim (priests). The sole exception is the most humble and least visible of them all: the michnisei bahd (linen breeches), worn as undergarments. The formal instructions appear in Parashas Tetzaveh:

You make for [Aharon and his sons] linen breeches to cover the flesh of nakedness; from the hips to the thighs they should be. They shall be upon Aharon and upon his sons when they come to the Tent of Meeting, or when they approach the altar to minister in the Holy [place], that they not bear iniquity, and die; it shall be an everlasting statute for him and his seed after him. (28:42-43)

The Koren Tanakh of the Land of Israel: Exodus (39:28, p.221) describes them as follows:

The linen trousers were worn by Aharon and his sons as an undergarment under their tunics. A pair of linen trousers reached from above the navel down to the ankle. Inside the top hem of the linen trousers was a drawstring that allowed the priest to tighten them. The linen trousers were woven with thread composed of six strands of linen.

The Rambam (Hilchos Klei ha’Mikdash ve’ha’Ovdim Bo 8:18) codifies their design:

The pants—whether of the kohen gadol (high priest) or an ordinary kohen—extended from the hips to the thighs, i.e., from above the navel, near the heart, to the end of the thigh, which is the knee. They had sashes (i.e. drawstrings). They lacked both a rear and a front opening. (Alternatively: they were not form-fitting in the rear or the front.) Instead, they enclosed the body like a pouch.

Although the michnisei bahd are primarily discussed in Parashas Tetzaveh, they are first alluded to in the final verse of Parashas Yisro (22 or 23, depending on the edition):

And you shall not ascend My altar by steps, so that you not uncover your nakedness upon it.

Rashi (ibid.) explains:

And you shall not ascend My altar by steps – When you construct a ramp to the altar, you shall not build it with steps, (échelons in old French); rather, it shall be smooth and sloped.

so that you not uncover your nakedness upon it – Because of the steps, you would need to take wide strides. Even though this would not constitute a literal “uncovering of nakedness,” since it is written, “And you shall make for them inen breeches [to cover their naked flesh]" (ibid. 28:42), nevertheless, widening one’s strides is close enough to the uncovering of nakedness [that it may be described as such], and this would be a disrespectful manner of conduct toward them.

This follows a kal va’chomer (à fortiori argument): If, regarding these stones, which have no awareness, the Torah states, “Since they serve a utility, you must not treat them disrespectfully,” then with your fellow, who is made in the likeness of your Creator and is particular about any disrespect shown to him, how much more so [must you not treat him disrespectfully]!

According to Rashi, this law involves a chain of precautions: we are forbidden to ascend the altar by steps because that would require wide strides; wide strides could result in an uncovering of nakedness, even for the kohanim who wear michnisei bahd; such an uncovering would be considered disrespectful to the altar’s stones—and if we are commanded to avoid disrespecting stones, how much more so must we avoid disrespecting other people!

But as nice as it may be to draw a homiletical lesson in interpersonal ethics, is that really the Torah’s concern here? Let’s assume, for now, that Rashi is correct in saying that uncovering nakedness would constitute disrespectful conduct toward the altar. Isn’t that, in itself, a concern worthy of a Torah prohibition? Later, Hashem commands: “revere My sanctuaries” (Vayikra 19:30). Rambam (Hilchos Beis ha’Bechirah 7:1) explains:

It is a positive commandment to revere the Mikdash (Temple), as it is stated, “you shall revere My sanctuaries.” And it is not the Mikdash itself you revere, but the One Who commands its reverence.

Even if one argues that the reference at the end of Parashas Yisro applies to all altars, including private altars permitted before the permanent establishment of the Mikdash, their association with avodas Hashem (Divine service) would still warrant a measure of kavod (respect).

Indeed, Ramban (Shemos 20:22/23) writes, “The reason for [prohibiting] steps is the awe of the altar and its beautification for the glory of Hashem.” The Tur (ibid., peirush ha'aroch) similarly states that this was commanded “for the kavod of the altar; the reason is that it atones for the iniquities of Israel, and it is proper to honor it and glorify it.” Sefer ha’Chinuch (#41) elaborates, echoing Rashi’s reasoning but stopping short of the ethical lesson:

The root [reason] of this mitzvah is as we wrote in the previous one: to instill within our souls reverence for the place (i.e. the Sanctuary) and its significance. Therefore, we were warned not to behave there with any frivolity. Everyone knows that stones do not take offense at disgrace, for they neither see nor hear. Rather, the entire purpose is to impress upon our hearts a sense of reverence for the place, its significance, and its great honor—for through action, the heart is shaped, as I have written.

The explanation given by these Rishonim is far more conservative than the homiletical takeaway offered by Rashi.

Even more conservative are the explanations that focus on the phrases, “so that you not uncover your nakedness upon it (she’lo tigaleh ervasecha alav)” and “to cover the flesh of nakedness (lechasos besar ervah).” The term giluy ervah (uncovering of nakedness) is used throughout the Torah as a euphemism for forbidden sexual acts. Arguably, this is the only instance in the Chumash where giluy ervah is meant literally. It is therefore not surprising that the Sages (Arachin 16a) connect the michnisei bahd to sexual morality, teaching: “The breeches atone for giluy arayos (forbidden sexual relations), as it is written, ‘linen breeches to cover the flesh of nakedness.’”

Ralbag (Shemos 20:23, toeles #24) explains the relationship between michnesei bahd and sexuality:

In terms of character traits, this mitzvah teaches that nakedness is something disgraceful, and therefore, it is inappropriate for it to be exposed in sacred places—just as we see regarding the ramp used to ascend the altar. From this, one should learn not to be drawn after activities related to nakedness, for they are inherently disgraceful in their actions. Rather, one should engage in such activities only when necessary.

Rambam (Moreh 3:46) connects the verse’s sexual undertones to avodah zarah (idolatry):

You know how common the worship of [Baal] Peor was in those days. The practice was to expose oneself. So God commanded our kohanim to make breeches, “to cover their naked flesh” (Shemos 28:42) in worship – and even so, not to ascend the altar by stairs, “so that you not uncover your nakedness upon it.”

Leon Kass (Founding God’s Nation: Reading Exodus, pp.492-494) picks up on this same connection and expounds, with my emphases in bold:

Finally, there is the perversity of sexual wildness and forbidden unions often associated with religious practice. This suggestion gains support from the final article of clothing, the britches, where the danger of the priests’ own iniquity is explicitly mentioned.

And you shall make them [Aaron and sons] linen breeches to cover the flesh of their nakedness; from the loins even unto the thighs they shall reach. And they shall be upon Aaron, and upon his sons, when they go in unto the Tent of Meeting, or when they come near unto the Altar to minister in the Holy place; that they bear not iniquity, and die; it shall be a statute forever unto him and unto his seed after him.

Were it not for the previous passage about iniquity, the mention of britches – undergarments, from the loins to the knees – would appear to be simply an afterthought. As it is, they are quite a comedown from the golden plate proclaiming "Holy to the Lord" that crowns the High Priest's forehead: from the sublime to the ridiculous. Yet there seems to be a connection between the high and the low, especially among the priests. The term for britches, mikhnasayim, occurs in the Bible only in connection with the priestly garb. We know from outside sources that underwear was not everyday apparel for anyone but the priests, and yet underwear was not previously mentioned as part of their glorious and beautiful trousseau. (Unlike their other garments, into which the priests are helped by others, the britches they must put on by themselves.) Yet with thoughts of iniquity nearby, the Lord makes sure to add that the britches are “to cover the flesh of their nakedness.” From the splendid coats of many colors, we are taken back to the Garden of Eden and the concern with covering up. The danger is sexual and not trivial.

It should be noted that Kass understands the verse, “And they shall be upon Aaron, and upon his sons … that they shall not bear iniquity, and die” as referring specifically to the michnisei bahd. This follows the reading of Ramban (ibid.) in contrast to Rashi (ibid.), who holds that this verse refers to all the garments. According to this reading, the Torah’s assignment of the death penalty strongly underscores the urgency and significance of the ideas associated with the breeches. Kass continues:

Already in Exodus 20, in connection with the earthen altar He mentioned to Moses, the Lord had shown concern about indecent exposure connected with sacrifices:

“Neither shall you go up by steps unto My altar, that your nakedness not be uncovered (lo’-thiggaleh ‘ervathekha) thereon” (20:23).

Priests, not having yet been appointed, were not mentioned; neither were britches. But an implicit concern was expressed that the activity of sacrifice would release inhibitions and arouse primal sexual passions. As scholars have noted, priests in neighboring cultures used to perform the sacred rituals in a state of nakedness (and arousal), and artwork shows that Egyptian priests wore only a short apron. Neighboring peoples employed temple prostitutes, and sex with animals was also incorporated into pagan religious rituals – targets of some of the apodictic (and capital) ordinances discussed in Chapter Fifteen. Finally, as we will see in the episode with the golden calf, the impulses to idolatrous worship and orgiastic sexuality keep company with one another. For good reasons, even the High Priest of Israel must be protected from his own iniquitous propensities. Reminding the reader of the proper procreative direction of sexuality, the Lord concludes by telling Moses that the covering of the priest's nakedness shall be a statute forever, for him and for his seed after him.

In sum, the michnisei bahd were designed to enhance reverence of the Mikdash, to distance us from sexual immorality, to curb primitive idolatrous instincts, and—according to Rashi—to reinforce proper conduct toward our fellow man. They are truly philosophical pants, befitting the kohanim who minister to Hashem in the Mikdash. Suffice it to say, the values that shape the design and role of modern undergarments in secular Western society stand in stark contrast to those of the Torah.

Which of these explanations of the michnisei bahd do you find most compelling? Do you know of any other explanations?

Like what you read? Give this article a “like” and share it with someone who might appreciate it!

Want access to my paid content without actually paying? If you successfully refer enough friends, you can get access to the paid tier for free!

Interested in reading more? Become a free subscriber, or upgrade to a paid subscription for the upcoming exclusive content!

If you've gained from what you've learned here, please consider contributing to my Patreon at www.patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss. Alternatively, if you would like to make a direct contribution to the "Rabbi Schneeweiss Torah Content Fund," my Venmo is @Matt-Schneeweiss, and my Zelle and PayPal are mattschneeweiss at gmail. Even a small contribution goes a long way to covering the costs of my podcasts, and will provide me with the financial freedom to produce even more Torah content for you.

If you would like to sponsor a day's or a week's worth of content, or if you are interested in enlisting my services as a teacher or tutor. Thank you to my listeners for listening, thank you to my readers for reading, and thank you to my supporters for supporting my efforts to make Torah ideas available and accessible to everyone.

-----

Substack: rabbischneeweiss.substack.com/

Patreon: patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss

YouTube: youtube.com/rabbischneeweiss

Instagram: instagram.com/rabbischneeweiss/

"The Stoic Jew" Podcast: thestoicjew.buzzsprout.com

"Machshavah Lab" Podcast: machshavahlab.buzzsprout.com

"The Mishlei Podcast": mishlei.buzzsprout.com

"Rambam Bekius" Podcast: rambambekius.buzzsprout.com

"The Tefilah Podcast": tefilah.buzzsprout.com

Old Blog: kolhaseridim.blogspot.com/

WhatsApp Content Hub (where I post all my content and announce my public classes): https://chat.whatsapp.com/GEB1EPIAarsELfHWuI2k0H

Amazon Wishlist: amazon.com/hz/wishlist/ls/Y72CSP86S24W?ref_=wl_sharel