The Mishleic Spectrum: A Glossary of Mishlei Personalities

If you are interested in Mishlei methodology, I highly recommend that you read Saadia Gaon's Introduction to Mishlei, How to Learn Mishlei: a Step by Step Guide, and Mishlei Methodology: Meiri - Nigleh and Nistar. Those three posts, together with this one, constitute my online "Mishlei 101" class.

Click here for a printer friendly version of this blog post. It is recommended to print this in color.

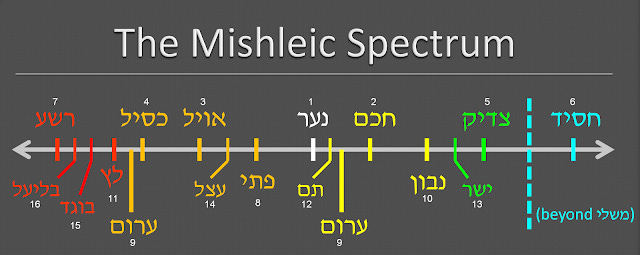

The terms on this chart will be translated, defined, and explained in the post below - after an introduction.

The Mishleic Spectrum: A Glossary of Mishlei Personalities

What This Is, and What This Is Not

Several years ago my Mishlei rebbi and I sat down to write a book on Mishlei. Our goal was to write a "Mishlei Primer" comprised of three parts: (1) a methodological "How to Learn Mishlei" guide, and (2) a Mishlei Glossary, in which we would provide definitions for the many terms and personalities of Mishlei, and (3) a "sampler" of pesukim and their explanations, in accordance with our method.

We decided to begin our research with two of the most obscure Mishleic personalities: the bogeid ("Traitor") and the bliyaal ("Lawless Person"). We ended up spending the whole summer trying to define those two personalities, and we didn't get any further. The following year we tackled the atzel ("Lazy Person"), and spent the whole summer working on that. Suffice it to say, writing a Mishlei glossary was more difficult than we thought at the outset. We shelved the project and haven't returned to it since.

In retrospect, I think that the standard we established for ourselves was too high. We set out to define each of these terms to the best of our understanding, with the greatest degree of certainty we could muster. This led to a continual revision, re-revision, and re-re-revision of our definitions. For instance, we ended up learning through every pasuk in Mishlei about laziness a total of six times; we started with the first pasuk, then moved on to the second, and so on - but by the time we got to the final pasuk, we felt the need to relearn all of the pesukim again in light of our updated understanding. This was great in terms of our own learning, but not great in terms of our project.

Perhaps what we should have done is to try to figure out working definitions instead of absolute definitions. Our goal should have been to provide definitions which were clear to enable the beginner to get started, but without aiming to definitively proclaim, "This is Mishlei's definition of tzadik" or "This is what Shlomo ha'Melech meant by chochmah."

This more realistic goal is what I intend to accomplish here, in my rough draft of a "Mishleic Glossary." My goal is to provide working definitions - NOT absolute, authoritative, definitive definitions - of primary, secondary, and some tertiary Mishleic personalities. This definitions in this dictionary should be clear enough to consult and use in case you get stuck on a pasuk and need to "plug in" a definition to work with until you are able to arrive at your own understanding.

Understanding Mishleic Labels

It should be noted that Mishlei speaks in absolutes. Shlomo ha'Melech will say things like, "The ksil (fool) does such-and-such, but the chacham (wise man) does such-and-such" - as if "the ksil" and "the chacham" are living, breathing individuals whom you might run into one day on the street.

In reality, this isn't the case. Real human beings are complex, and don't fit neatly into Mishleic labels. It is entirely possible for the same individual to be a chacham in his business dealings, an atzel when it comes to Torah study, a rasha in his relationships, and a chasid in halacha. To an extent, we all have elements of ALL Mishleic characteristics within ourselves, in different proportions.

Mishlei's labels should be thought of as archetypes or paradigms. From a pedagogical standpoint, it is much easier for Shlomo ha'Melech to teach the reader how to become a chacham and avoid the pitfalls of a fool by describing "pristine" decision-making scenarios involving a prototypical chacham character and a prototypical fool character as his foil.

Sources (or Lack Thereof)

Each of the meforshim (commentators) on Mishlei has his own understanding of the terms we are about to discuss. Some meforshim state their definitions explicitly and bring support from other pesukim or Chazal. Other meforshiim simply explain the pesukim in accordance with their understanding, and the reader of Mishlei must infer their implicit definitions.

The definitions in this post reflect my current "working definitions" as of June 13th, 2017. Some of these can be traced back to explicit statements provided by pesukim, statements of Chazal, and other meforshim; other definitions I have inferred from their commentaries, some of these definitions are from my Mishlei rebbi, and some are the result of my own Mishleic knowledge and intuition (which I have been cultivating over the past 16 years of uninterrupted Mishlei learning).

Likewise, the arrangement of these Mishleic personalities on a spectrum is the result of my own analysis, synthesized from a number of different meforshim. There is no unanimous agreement as to where each personality falls out on the spectrum. For example, some (like myself) view the tzadik as a further development of the yashar; others flip the two.

I have chosen not to cite any sources for these definitions, since this would be a herculean task which I am not up to at the moment. Instead, I will now identify my "go to" meforshim from which these definitions were drawn. The five meforshim I used the most, in order, are: Meiri, Rabbeinu Yonah, Saadia Gaon, Metzudas David, and Ralbag. These are the five meforshim who, along with my Mishlei rebbi, gave me a derech (method) of Mishlei, and have shaped my development of my own derech.

Color Code

I've decided to color-code the labels in my spectrum, to add a layer of clarity:

Without further ado, here are sixteen Mishleic personalities - presented in the most suitable conceptual order.

A Glossary of Mishleic Personalities

Primary Mishleic Personalities: these are the ones I focus on in my introductory Mishlei classes, since they are the most basic; all other personalities are subdivisions within these.

1. נער - Naar ("Youth"): the average person who hasn't learned Mishlei. The term "youth" isn't a reference to age, but to wisdom - just as the Torah uses zakein ("elder") in reference to someone who has acquired much wisdom, regardless of his age. The naar has had enough life experience to form his own views, personality, and habits, but for the most part, he has no major flaws which stand in the way of Mishlei learning and Mishleic development. The naar is one of the audience members for whom Shlomo ha'Melech intended his book, as it is stated: "to [provide] the naar with knowledge and intelligent planning" (Mishlei 1:4).

2. חכם - Chacham ("Wise Person"): one who makes decisions based on long-term consequences. Chazal express this definition in the dictum: "Who is a chacham? One who sees the consequences [of his decisions]" (Tamid 32a). The chacham wants to maximize pleasure and minimize pain. He realizes that in order to do this, he must make decisions using his intellect and not just act based on his feelings and whims. When faced with a decision the chacham will weigh the long-term benefits/pleasures against the short-term pain/harm, and the long-term painful/harmful consequences against the short term pleasures/benefits. Shlomo ha'Melech also intended Mishlei to be learned by chachamim, who are still developing in their chochmah towards becoming tzadikim, as it is stated: "the chacham will hear [the words of Mishlei] and increase his learning" (Mishlei 1:4).

3. אויל - Eveel ("Foolish Person"): one who seeks immediate gratification. The eveel is the opposite of the chacham. He is so caught up in his single-minded pursuit of immediate gratification that he will choose short-term pleasure/benefit even if this brings about long-term pain/harm, and he will forego long-term pleasure/benefit if the price is short-term pain/harm. This severely limits the perspective of the eveel, restricting his view of reality to a superficial level. Although it might be possible to reach the eveel through Mishlei, this is an uphill battle. For this reason, the eveel is not included in Shlomo ha'Melech's intended readership.

NOTE: Mishleic fools (i.e. eveel, ksil, pesi, arum, etc.) should NOT be thought of as "stupid" in the sense of having a low IQ, nor should they be thought of as bumbling imbeciles. In Mishlei "foolishness" refers to a flawed pattern/habit of decision-making - not a lack of intelligence. It is possible to be extremely smart but still be classified as a "fool" according to Mishlei.

4. כסיל - Ksil ("Fool"): one who is addicted to immediate gratification to the extent that he unconsciously expects reality to align itself with his desires. The ksil is similar to the eveel in his superficial outlook on reality and his focus on immediate gratification - so similar, in fact, that many of the meforshim seem to regard the two terms as synonyms. But to my mind, there is one important difference: the ksil has an arrogance which the eveel lacks. The eveel's resistance to chochmah stems from his dim recognition that chochmah threatens his mindless pursuit of immediate gratification. In contrast, the ksil is attached to a worldview with himself at the center; his resistance to chochmah stems from his vested interest in this egocentric worldview. Unlike the chacham, who recognizes that he must align himself with reality to get what he wants, the ksil expects reality to yield to his will. The difference between the eveel and the ksil might seem minor, but it is this modicum of arrogance which allows the ksil to develop into something worse (i.e. leftward on the Mishleic spectrum), whereas the eveel will usually remain locked in place. Furthermore, the ksil displays a degree of stubbornness and close-mindedness which the eveel lacks. To use an analogy: if chochmah is the father, the eveel is the kid being dragged to the school bus kicking and screaming, whereas the ksil is the kid with crossed arms and an angry face who has firmly planted himself behind the locked doors of his bedroom.

5. צדיק - Tzadik ("Righteous Person" or "Person of Justice"): one who makes decisions based on the good of the system, as a whole, of which he is a part. The tzadik may be thought of as "the finished product" of the Mishlei Program. Like the chacham, the tzadik thinks long-term, but whereas the chacham's long-term thinking is linear - and therefore, limited - the tzadik's is systemic. For those who think visually, perhaps this diagram will clarify what I mean by "linear" vs. "systemic":

Here is the explanation of this diagram:

The perspective of the eveel is limited in two ways: (a) his thinking is extremely short-term, and (b) when he does think ahead, he can only think in a linear fashion ("If I do A, then B will happen.")

The perspective of the chacham is broader: (a) his thinking is long-term, but (b) it is also limited to a linear perspective.

The perspective of the tzadik is even broader than that: (a) his thinking is long-term, but extends beyond the long-term thinking of the chacham because (b) he thinks systemically ("If I do A, this will have an impact on the entire system, which will bring about B, C, D, etc.").

To further clarify, here are three examples to illustrate the differences between the decision-making of an eveel, a chacham, and a tzadik.

SCENARIO #1: LOST OBJECT

When an eveel encounters a lost object, he will either take it for himself, if he wants it (seeking of short-term pleasure), or he will leave it there and move on if he doesn't want it (avoidance of short-term pain).

A chacham would make an effort (short-term pain) to return the lost object to its owner knowing that this might yield long-term benefits (e.g. a reward, goodwill, being owed a favor, increasing the likelihood that the owner of the lost object will look out for the chacham's lost objects, being viewed as an honest and caring person, etc.).

A tzadik would also return the lost object; he is aware of the long-term benefits that motivated the chacham, but he will think beyond those benefits and consider how his action will impact the system of which he is a part. The tzadik knows that by returning this lost object, he will contributing to a society (e.g. school, workplace, neighborhood, etc.) in which people care about each other's possessions. Such a society is beneficial for all of its members - including the tzadik himself. For this reason, the tzadik - unlike the chacham - will return the lost object even if there is no chance of a direct personal benefit which will result from his efforts. He views the short-term cost of returning the lost object as an investment in the greater long-term benefits of shaping his society for the better.

SCENARIO #2: STEALING

An eveel will have no problem cheating or stealing. The prospect of immediate gain will overshadow the consequences that he might suffer as a result. He is likely to either not think about the possibility of getting caught, or hastily convince himself that he won't get caught.

A chacham will refrain from cheating and stealing. He knows that the consequences of getting caught far outweigh the short-term gains. He knows that even if he doesn't get caught this time, it will be extremely difficult to limit himself after stealing just one time. That initial crime will make it easier for him to rationalize stealing again, and again, and again. Eventually, he will get sloppy, or take too big of a risk, and he will get caught and suffer the consequences. Moreover, this will tarnish his reputation, which will make it even harder to make an honest profit in the future.

A tzadik will factor in all of the pros and cons considered by the chacham, but he will also think about how his actions will impact the system of which he is a part. For example, if he steals a pen from his colleague in the office, this might lead his colleague to feel that it is okay to do the same thing. Not only would this put his own pens in danger from being stolen by that colleague, but it would push the entire office one step closer to being a society in which people don't respect each other's ownership. This disregard for personal property might extend to other areas as well (e.g. failing to clean up after themselves in the cafeteria, not pulling their weight in shared responsibilities, not being willing to cover for each other in extenuating circumstances). This might seem like a slippery slope type argument, but the tzadik knows that this is how systems devolve: one self-centered decision at a time. "No snowflake in an avalanche ever feels responsible."

SCENARIO #3: EATING

An eveel will eat foods which yield short-term pleasure and will shun foods which would bring him short-term displeasure - even if these eating habits leads to harmful consequences in the long run (e.g. health problems, image problems, financial costs) and the withholding of long-term benefits (e.g. living longer, being able to enjoy old age, being able to continue eating the foods that he has become accustomed to enjoy).

A chacham will eat foods which yield long-term benefit/pleasure and enable him to avoid long-term pain/harm - exactly the opposite of the eveel.

A tzadik shares all of the chacham's motives, but his concern will extend beyond these personal, linear benefits to the entirety of system of which he is a part. For example, if he is a father in a household with a wife and kids, he will eat healthy for his own sake and for the sake of his family as well. Maintaining his long-term health will increase the chances of him being there for his family in the future. If he and his wife eat healthy, their kids will grow up eating healthy as well. Not only will they benefit from the diet itself, but they will have grown up with parents who regularly exercised self-control in the realm of the appetitive. Not only that, but if he and his wife eat healthy, and their kids eat healthy, then this increases the likelihood of healthy progeny all the way down the line.

I hope the diagram and scenarios clarified these three terms. Back to the glossary.

6. חסיד - Chasid ("Pious Person"): one who goes beyond what is required. This definition is intentionally vague because it deals with a subject matter outside of Mishlei; its usage will differ based on the framework and context in which it is used. For example, in Tehilim the term "chasid" has to do with one's relationship to Hashem - going beyond what is required and acting in accordance with His design and His plan. In Pirkei Avos, the term "chasid" denotes lifnim mi'shuras ha'din (going "beyond the letter of the law") within the system of Taryag Mitzvos. In the Rambam's Hilchos Deos, the term "chasid" refers to an extra degree of vigilance and management in one's own ethical development. The common denominator is that a chasid's actions are characterized by chesed ("excess"), going beyond what is required. I only included the term in this glossary to show that it is barely dealt with in Mishlei.

7. רשע - Rasha ("Evil Person"): one who seeks to impose his own system onto reality in order to achieve power and greatness. The rasha is the opposite of the tzadik. The tzadik strives to understand the system of which he is a part, and to facilitate the good of that system as a whole. In contrast, the rasha wishes to dominate others and to emerge on top as the greatest and most powerful being. He will do whatever it takes to force this design upon the existing circumstances. Since this is an artificial scheme, rooted in a fantasy-driven megalomania, it will inevitably clash with what is good for the other members of the system, and many people will be trampled and harmed in the rasha's rise to power. The rasha's personality is best exemplified by people like Paroh, Haman, and Hitler (shem reshaim yirkav) - all of whom sought to subjugate others in an attempt to reshape the world into a shrine for their own glory. Ultimately, the rasha is doomed to fail when his delusional master plan clashes with reality. For Paroh, this failure was brought about by Hashem; for Haman, it was orchestrated by Mordechai and Esther; for Hitler, it resulted from his overambitious attempts to extend his reign beyond what was possible (e.g. his failed attempt to invade the Soviet Union).

NOTE: For the most part, each term on the right-hand side of the spectrum builds upon, and includes, the qualities of the previous level. For example, the tzadik includes all the characteristics of the navon, who includes all the features of the chacham. But on the left-hand side of the spectrum, this isn't necessarily true. The ksil embodies all the qualities of the eveel, but the rasha doesn't share the features with either of them. In fact, in order to be a rasha, one must possess the long-term thinking of the chacham. Consider Hitler. He certainly wasn't an eveel or a ksil. Hitler needed to think long-term - and even forego immediate pleasure and endure immediate pain - in order to realize his ego-maniacal vision. The only area in which the rasha is a ksil is when it comes to the end-game. The rasha is blind to the fact that his grand vision is built upon a foundation of falsehood fueled by a denial of reality (i.e. refusal to acknowledge that he is a limited, finite particular within a natural system - not an omnipotent god-like ruler of a self-glorifying system of his own design).

Secondary Mishlei Personalities: these show up with near-equal frequency, but represent variations on - and transitional phases between - the basic personality types.

8. פתי - Pesi ("Naive Simpleton"): one who is easily "seduced" (mispateh) by his own emotions. The pesi is extremely subject to external influences. The principle which drives his life may be summed up as follows: if it feels true then it is true, and if it feels good then it is good; likewise it feels bad then it is bad, and if it feels false then it is false. The pesi shares qualities with the eveel and the naar. He resembles the eveel in that he views reality in a superficial way. He resembles the naar in that he can be positively influenced by Mishlei. The eveel and the ksil are "locked" into their flawed ways of thinking. The pesi, thanks to his malleable mind, can be guided towards the good by chachamim and tzadikim. For this reason, Shlomo ha'Melech included the pesi in his intended audience - something he didn't do for any other Mishleic fool - as it is stated: "to provide pesaim with cunning" (Mishlei 1:4).

9. ערום - Arum ("Cunning Person"): one who has a working knowledge of how emotions influence decision-making. You'll notice that the arum appears in two places on the spectrum: slightly to the right of the naar (on "the good side") and on the borderline of the group of the evildoers (on "the bad side"). The reason for this is simple: the arum's cunning (i.e. his working knowledge of the psyche and its capacity to influence behavior) is a tremendous gift which can aid his development into a chacham or be used in the pursuit of foolish or wicked ends. The arum has a leg up over the naar because he is keenly aware of how much his own thinking might be influenced by his emotions; if he is wise, this will give him pause in his decision-making - and if he makes this into a habit, then he will be well on his way to becoming a chacham. On the other hand, the arum is also in the perfect position to manipulate others for sinister purposes - as the Torah itself states, "The snake was more cunning than all the other beasts of the field" (Bereishis 3:1). This type of cunning is a valuable tool in the rasha's arsenal, and is essential for his success. In short, the arum is a potential chacham and a potential rasha.

10. נבון - Navon ("Understanding Person"): an abstract thinker (i.e. one who can inductively derive new universal principles from particulars and deductively apply universals to new particulars). This is one of the few definitions which all of the meforshim agree upon. The question is: How does he fit into this spectrum? I'm not entirely clear on that point. Descriptively, the navon represents the transitional stage between the chacham and the tzadik. The chacham must be able to do more than see the long-term consequences of a particular decision. He must be able to uncover universal principles of decision-making from his day-to-day situations, which will allow him to expand his chochmah to new scenarios. Abstract thinking is also necessary to break out of the linear thinking of the chacham and to view things systemically like the tzadik. The navon is also mentioned as a primary audience of Mishlei, as it is stated: "[through Mishlei] a navon will acquire strategies" (Mishlei 1:4).

11. לץ - Leitz ("Scoffer"): an egotistical person who is malicious in speech (but not in action). This definition comes directly from a pasuk in Mishlei: "The arrogant malicious one - 'leitz' is his name" (21:24). The leitz has a massively inflated ego which stems from a deep-seated feeling of deficiency and inferiority. Instead of dealing with his flaws through chochmah, he denies his imperfections and degrades others to artificially boost his self-esteem. His self-confidence is so low that he doesn't even take proactive measures to boost his own standing, but instead takes the cowardly approach of speaking rechilus (gossip), lashon ha'ra (negative speech), and hotzaas shem ra (slander) behind people's backs. The leitz is the school bully - not the one that beats kids up and steals their lunch money, but the one who cuts them with hurtful words and makes fun of them in public. The best and worst thing about the leitz is that he is all talk, and no action. This is good in the sense that one don't have to worry about him causing physical damage to oneself or to one's possessions. This is bad in that the leitz can cause a LOT of harm through speech.

Tertiary Mishleic Personalities: these don't appear too often, and this isn't an exhaustive list. Like the secondary personalities, they are variations on the basic types, or transitional phases between developmental milestones.

12. תם - Tam ("Evenly Keeled Person"): one who has no extreme emotions pulling him in either direction. The tam is a "beginning personality" like the naar, but has a huge advantage over the latter. In all probability, the naar is likely to be a mixed bag. While he doesn't have any outstanding flaws in his way of operating (like the eveel and the ksil), he is bound to have certain weaknesses and deficiencies in his middos/personality. He might have a short temper, or be prone to jealously, or have problem managing his money, or be overly timid or overly reckless, or overly competitive or not competitive enough, etc. In contrast, the tam is balanced. His emotions are fluid, and provide little to no resistance. If the situation calls for him to save money, he'll be able to do it. If the situation calls for him to spend money, he will spend it without any conflict. If he needs to be self-assertive, he'll be self-assertive. If he needs to remain in the background, this will not cause him any conflict. Although it is possible to become a tam through the proper training, some people are fortunate to naturally be tamim. We all know certain individuals who are calm, cool, and collected, and don't seem to be disturbed or agitated by anything. Chances are that such an individual is a natural tam. The next step for such a person is to learn how to think like a chacham, which will be much easier for him to do without personality-obstacles and emotional resistances.

13. ישר - Yashar/Yosher ("Upright" Person): one whose inclinations and intuition draw him towards tzedek (what is good for the system), but without a working understanding of the system. Out of the sixteen terms on this chart, this is the one I understand the least. Descriptively, this is a navon on his way to becoming a tzadik. He frequently makes the same decisions that a tzadik would make, but not in the systematic manner of the tzadik. The tzadik consciously does what is best for the system, with forethought and full understanding. The yashar intuitively acts this way, but he hasn't taken that final developmental step to make tzedek his modus operandi.

14. עצל - Atzel ("Lazy Person"): one who compulsively attempts to avoid all immediate pain and conflict. Like the eveel, the atzel is locked into the superficial world of immediate pain and pleasure. But unlike the eveel, who seeks immediate gratification above all, the atzel is paralyzed by the compulsive need to avoid immediate pain. In Scenario #1 (about the lost object), the atzel will usually just leave the object where it is, since it's too much work to take it. In Scenario #2 (about stealing) the atzel wouldn't steal in a proactive effort to increase profits, but he might steal if it helps him to avoid work or conflict. In Scenario #3 (about food) the atzel won't necessarily go for the most pleasurable food; he'll just eat whatever takes the least effort, even if he doesn't really like it as much.

15. בוגד - Bogeid ("Traitor" or "the Mishleic Jerk"): one who repays good with bad and impulsively "lashes out" at reality when things don't go his way. This is also a difficult personality to understand. In a sense, the bogeid is as the opposite of the yashar. The yashar's intuition is in line with reality (i.e. tzedek, or "the system"), but the bogeid's intuition routinely brings him in conflict with reality. In the social realm he has no intuitive sense of justice or basic decency, and will act like a jerk even to those who benefit him and treat him kindly. Deep down, he has an anthropomorphic view of reality (i.e. he relates to reality as though it were a person); consequently, he takes reality personally, and will vent his frustration by complaining and acting out when he feels "victimized." Both the bogeid and the ksil have a strong sense of entitlement, but whereas the ksil's sense of entitlement causes him to walk around with a false sense of security leading to proactive self-sabotage, the bogeid's sense of entitlement causes him to throw frequent tantrums and engage in reactive self-sabotage.

16. בליעל - Bliyaal ("Lawless Person"): one who cannot tolerate being subjugated to any authority. The word bliyaal is a compound of bli (without) + ole (yoke). The essence of his personality is that he does not want to feel controlled, ruled, or dominated by anyone. He is anti-authoritarian - not in a philosophical way, but in a "wild animal" or "stubborn child" way. Like the bogeid, the bliyaal has an anthropomorphic view of reality, to the extent that when reality "obligates" him to do something, he rebels. For example, he won't plant his field during the planting season because he unconsciously feels: "How DARE they make me plant! Nobody is gonna tell ME what to do!" Like the leitz, the bliyaal derives enjoyment from causing destruction and harm - not because he shares the leitz's sadism and malice, but because wreaking havoc in this manner makes him feel independent and unrestrained. The only authority to whom the bliyaal will pledge his loyalty is the rasha, so long as the rasha gives him an outlet for his lawlessness. It is for this reason that you will see examples of bliyaal in the second tier of criminal hierarchies (e.g. mafia strongmen, gang members who do the dirty work for gang leaders, Nazis who were given outlets for their sadism by being assigned positions of authority in concentration camps).

Conclusion (for Now)

I repeat: these definitions are not authoritative, nor are they set in stone. These are working definitions intended to aid the beginning in learning Mishlei until he or she forms his or her own understanding.

There are more personalities in Mishlei that I haven't even touched upon here: the ish mezimos ("scheming person"), the meivin ("discerning person"), the ben meivish ("embarrassing son"), the charutz ("diligent person"), the ish chamas ("violent person"), the chasar lev ("one who lacks an understanding mind"), and more. Perhaps I will define these in the next edition of the Mishleic Glossary.

For now, I hope you find this guide to be useful in your own Mishlei learning!