The Sin of Columbus, Yehoyakim, and American Jewry

This article began as 4th of July musings about Columbus which illuminated my understanding of Yehoyakim, then morphed into a reflection on our values as American Jews in preparation for Tishah b'Av.

The Torah content for the month of July has been sponsored by the Richmond, VA learning community, “with appreciation for Rabbi Schneeweiss’s stimulation of learning, thinking, and discussion in Torah during his scholar-in-residence Shabbos this past June.” Thank YOU, Richmond, for your warmth, your curiosity, and your love of Torah! I'm already excited for my next visit!

Click here for a printer-friendly version of this article and click here for

The Sin of Columbus, Yehoyakim, and American Jewry

Disgruntled disclaimer: This was an incredibly tricky article to write. I’ve worked on it for so long that I can no longer tell whether it has any merit. I’m forcing myself to stop working on it now so that I can move on to preparing for my Tishah b’Av shiur. Please let me know what you think — especially if you find it insightful on any level.

The Sin of Columbus

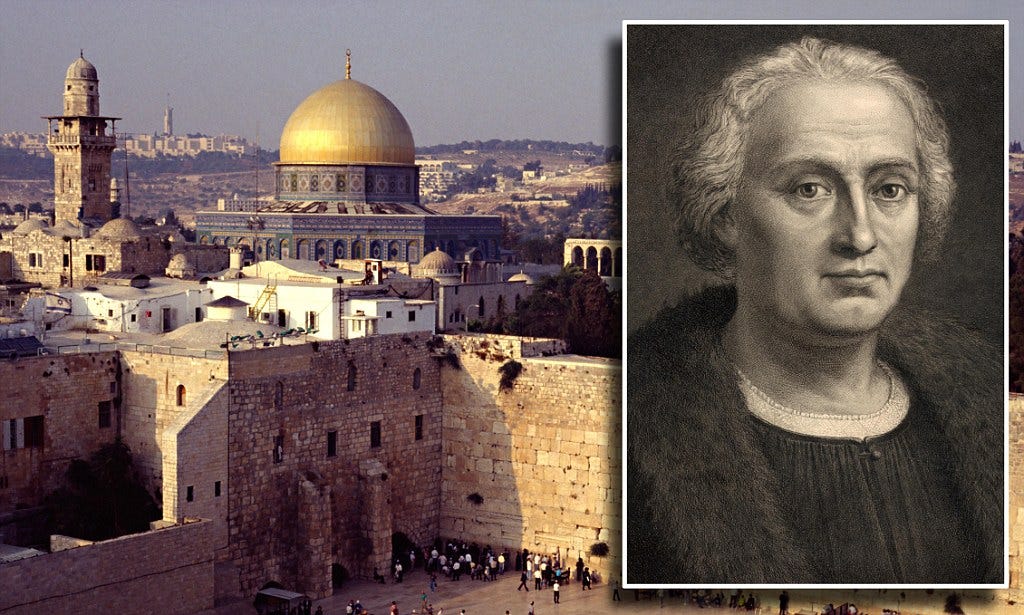

This past July 4th I found myself in the mood to read something that would prompt me to reflect on America. Since I’ve been on a Barry Lopez kick this summer, I purchased and read The Rediscovery of North America (1990) — a slim book in which the author shares his views on the fundamental “sin” (my term, not his) of Christopher Columbus, and the ripple effects of that sin throughout the subsequent centuries.

Before you jump to conclusions, rest assured: you are NOT going to guess what that sin is.

If your guess is that Christopher Columbus and his men were barbaric, you would be correct in your assessment, but incorrect in thinking that this was Lopez’s diagnosis. To be sure, Lopez mentions Columbus’s barbarism, writing:

What followed for decades upon this discovery [of the Americas] were the acts of criminals — murder, rape, theft, kidnapping, vandalism, child molestation, acts of cruelty, torture, and humiliation. Bartolomé de las Casas, who arrived in Hispaniola in 1502 and later became a priest, was an eyewitness to what he called “the obdurate and dreadful temper” of the Spanish, which “attended [their] unlimited and closefisted avarice,” their vicious search for wealth. One day, in front of Las Casas, the Spanish dismembered, beheaded or raped three thousand people. “Such inhumanities and barbarisms were committed in my sight,” he says, “as no age can parallel …” The Spanish cut off the legs of children who ran from them. They poured people full of boiling soap. They made bets as to who, with one sweep of his sword, could cut a person in half. They loosed dogs that “devoured an Indian like a hog, at first sight, in less than a moment.” They used nursing infants for dog food.

I first learned of this dark history by reading Matt Inman’s The Oatmeal comic entitled Christopher Columbus was awful (but this other guy was not), in which the artist details other examples of the heinous acts committed by Columbus and his men. For example, if the natives they enslaved to search for gold failed to meet their quota, "Columbus's men would cut off the natives' hands and force them to wear [their severed hands]." Columbus "ordered that the "ears and noses [of the natives] be cut off, so that the now disfigured offenders could return to their villages and serve as a warning to others." Columbus was in the habit of “rewarding his lieutenants with sex slaves — particularly young girls … between the ages of nine and ten.”

Lopez acknowledges these horrific deeds, but doesn’t regard them as the essential Columbian sin. Nor does he identify this sin as greed, even though this was undoubtedly the driving force behind their cruelty:

[This] incursion, this harmful road into the “New World,” quickly became a ruthless, angry search for wealth. It set a tone in the Americas. The quest for personal possessions was to be, from the outset, a series of raids, irresponsible and criminal, a spree, in which an end to it — the slaves, the timber, the pearls, the fur, the precious ores, and, later, arable land, coal, oil, and iron ore — was never visible, in which an end to it had no meaning. (p.9)

So, what was the fundamental sin of Columbus and the the Spaniards who sent him? Lopez answers:

The Spanish sought a narrowly defined wealth. Las Casas writes, “Now the ultimate end and scope that incited the Spaniards to endeavor the extirpation and desolation of this people was gold only, that thereby growing opulent in a short time they might arrive at once at such degrees and dignities as were in no ways consistent with their persons.” (p.15)

True, their unchecked aggression and unbridled avarice were evil, but the foundation of these evils was a flawed value system in which wealth was measured in gold and the prestige that came with it.

Why does Lopez opt for the strange formulation of their error as “narrowly defining wealth”? Because there was another type of wealth that the New World had to offer. This type of wealth was not only disregarded, but was destroyed and lost in the mad chase for a wealth that glittered. What was the true wealth? Knowledge — knowledge of the good, the bounty, and the ways of peaceful coexistence with nature that the Land and its people possessed. Lopez elaborates on the tragedy of this myopia:

What wealth did Bermeo cry out in anticipation of? … the record tells us that in the end, there was very little imagination here — it was gold, silver, pearls, slaves, and sexual intercourse. It was venal greed, a failure of imagination, the reduction of desire to its most banal elements. True wealth — sanctity, companionship, wisdom, joy, serenity — these things were not to be had without an offer of heart and soul and time. The Spaniards had no time, and we find it easy to say on the evidence that they were heartless and immoral. The only wealth they could imagine was what they took …

The true wealth that America offered, wealth that could turn exploitation into residency, greed into harmony, was to come from one thing — the cultivation and achievement of local knowledge. It was in the pursuit of local knowledge alone that one could comprehend the notion of a home and its attendant responsibilities. (pp.21-23)

This local knowledge is what Lopez describes in another essay (Six Thousand Lessons) as “human epistemologies, the six thousand spoken ways of knowing God.” In our text, Lopez laments the vast troves of knowledge that were thoughtlessly decimated:

We lost in this manner whole communities of people, plants, and animals, because a handful of men wanted gold and silver, title to land, the privileges of aristocracy, slaves, stables of little boys. We lost languages, epistemologies, books, ceremonies, systems of logic and metaphysics — a long, hideous carnage. (p.15)

He laments the shortsightedness of their grave failing:

More than a thousand distinct cultures, a thousand mutually unintelligible languages, a thousand ways of knowing. How can one compare intimacy with the facets of this knowledge to the possession of gold? How could we have squandered such wisdom in that search? (pp.26-27)

Perhaps without realizing it, Lopez echoes the words of King Solomon, who said: “Happy is a person who has found wisdom, a person who can derive understanding [from it], for its commerce is better than the commerce of silver, and its produce [is better] than fine gold. It is more precious than pearls, and all your desires cannot compare to it” (Mishlei 3:13-15). Columbus and the conquistadors who followed him were blind to the true wealth of the lands they pillaged, and blind to the irreversible crime of killing the goose that lay the golden eggs.

The Sin of Yehoyakim

Columbus’s sin of rejecting knowledge for the sake of profit and plunder was committed by none other than Yehoyakim (Jehoiakim), the evil melech Yehudah (King of Judah), son of the righteous melech Yoshiyahu (King Josiah). How do we know this? Because he is rebuked for this in the most explicit terms by Yirmiyahu ha’Navi (Jeremiah, the prophet). Before we read his rebuke, here is some background information from Rabbi Binyamin Lau, in Jeremiah: the Fate of a Prophet (2013):

Pharaoh Necho imposes an unbearable tax on Judah — one hundred talents of silver and a talent of gold. Jehoiakim pays it by levying a progressive tax upon the population: “every man according to his assessment.” We can only imagine how the people received this onerous tariff.

The true price is paid by society’s lowest classes, those without a voice, who can rail against injustice without anyone hearing them. The upper classes know how to cope with the tax — by lowering the wages of their underlings, negotiating with the government, and controlling the corridors of power. The king, loyal to Egypt whether he likes it or not, does not engage with the problems of the lower classes. He is eager to establish his regime by emphasizing the traditional symbols of royalty. In the earliest days of his reign, he plans an unprecedented building project: a new palace, which requires construction materials to be imported from throughout Egypt, and whose workers come from the lowest classes of society. The financing comes from the Egyptian government in a circular motion, as Egypt plunders the nations it subdues — Judah among them.

With this context, here are Yirmiyahu’s words of rebuke to Yehoyakim:

Woe to him who builds his house without righteousness and his upper stories without justice; who works his fellow without payment, and does not give him his wages; who says, “I shall build myself a house of large dimensions and spacious upper stories,” and he breaks open windows for himself, and it is paneled with cedar and painted with bright colors. Shall you reign just because you flaunt your cedar? Behold, your father ate and drank, but practiced justice and righteousness – then it went well for him. If one does justice to the poor and destitute, then it is good; is this not “knowing Me”? — the word of Hashem. But your eyes and heart focus on nothing but your profit, and upon innocent blood to shed, and to practice oppression and persecution. (Yirmiyahu 22:13-17)

To my mind, the most salient point in the navi’s rebuke is the woefully underappreciated (dare I say unknown?) definition of what it means to “know God,” which I will reiterate for emphasis: דָּן דִּין עָנִי וְאֶבְיוֹן אָז טוֹב הֲלוֹא הִיא הַדַּעַת אֹתִי נְאֻם י"י (“If one does justice to the poor and destitute, then it is good; is this not ‘knowing Me’? — the word of Hashem”). When Yirmiyahu, Yeshayahu, and the other neviim speak about knowledge of God, they are not talking about the abstract study of metaphysics, theology, and other branches of philosophy alone. Rather, they are referring to knowledge of Hashem which culminates in righteous conduct.

Without a doubt, the clearest statement of this idea can be found at the end of Yirmiyahu Chapter 9, in the two pesukim which I often say are the most important pesukim in all of Nach:

Thus said Hashem: "Let not the wise man praise himself for his wisdom, let not the strong man praise himself for his strength, and let not the wealthy man praise himself for his wealth, but only in this may the one who praises himself praise himself: comprehending and knowing Me, that I am Hashem, [Who] does kindness, justice, and righteousness on earth -- for in these is My desire," the word of Hashem. (Yirmiyahu 9:22-23)

Rambam (Moreh ha’Nevuchim 3:54) explains that the three invalid criteria for self-praise represent the three different types of perfection (or excellence) people tend to seek. The lowest of the three is “wealth”: perfection of possessions and status. These are external to man, have no actual connection with him (outside of their legal standing), and can be lost in an instant. A higher level of perfection is “strength”: excellence of the body in physical might, beauty, and health. Although this type of perfection “belongs” to man, it is external to his essence, is shared by animals, and deteriorates with age. An even higher level of perfection is “wisdom,” which, in this context, refers to the perfection of character traits. This type of moral excellence is valuable, but only as a means to an end. The end, the true human perfection, is “comprehending and knowing Me” — that is, knowledge of God, insofar as this is humanly possible. It is this perfection which is the true glory of man.

The Rambam goes on to clarify what Yirmiyahu means by “comprehending and knowing” God:

The prophet does not content himself with explaining that the knowledge of God is the highest kind of perfection: for if this only had been his intention, he would have said, "For only with this may one glorify himself - contemplating and knowing Me," and would have stopped there; or he would have said, "that he understand and know Me that I Am One,” or, "that I have not any likeness," or, "that there is none like Me," or a similar phrase. He says, however, that man can only glory in the knowledge of God and in the knowledge of His ways and attributes, which are His actions, as we have shown (1:54) in expounding the passage, "Show me now your ways” (Shemos 33:13). We are thus told in this passage that the Divine acts which ought to be known, and ought to serve as a guide for our actions, are, chesed, "kindness," mishpat, "judgment," and tzedakah, "righteousness."

In other words, the “knowledge of God” which constitutes true human perfection is knowledge of His ways (chesed, mishpat, tzedakah) which we emulate in our own actions. This is what Yirmiyahu means when he says, “If one does justice to the poor and destitute, then it is good; is this not ‘knowing Me’?” This is the knowledge of God that Yehoyakim rejected by oppressing the poor to increase his own wealth.

Yirmiyahu’s rebuke of Yehoyakim is entirely in line with Lopez’s critique of Columbus — so much so, that they can be seamlessly interwoven into a single admonition: “Woe to him who builds his house without righteousness and his upper stories without justice,” who builds his own wealth and the wealth of his country on the unjust rape of the land and its people, “who works his fellow without payment, and does not give him his wages,” who enslaves the powerless and ensures their descent into deprivation and annihilation. “your eyes and heart focus on nothing but your profit,” on the unchecked pursuit of material wealth, which is limited in quantity, neglecting the true wealth of knowledge, which is infinite in abundance, “and upon innocent blood to shed, and to practice oppression and persecution,” turning away from knowledge of Hashem and undermining His ways of chesed, mishpat, and tzedakah for your own misguided self-glorification.

The Sin of Klal Yisrael

It would be one thing if Yehoyakim’s sin were limited to his own actions during his limited reign. Sadly, the same sin plagued Klal Yisrael for the entire period of the Neviim Acharonim (Later Prophets). The rise of Yehoyakim was but a symptom of this national scourge.

The first navi to prophesy about the destruction of the Beis ha’Mikdash and the Babylonian exile was Yeshayahu, who repeatedly castigates Klal Yisrael for their ignorance, foolishness, and turning away from knowledge of God:

“An ox knows his owner, and a donkey his master’s trough; but Israel does not know, My people does not understand” (Yeshayahu 1:3).

“Therefore, My people has been exiled because of [their] lack of knowledge; its honored ones dying of starvation, and its multitude parched from thirst” (ibid. 5:13)

“They do not know and they do not understand; for their eyes are smeared, [prevented] from seeing and their minds from comprehension” (ibid. 44:18).

Yirmiyahu, the last navi to prophesy about the destruction, rebukes his people for the same sin, which persisted and compounded over the intervening generations:

“The Kohanim did not say, ‘Where is Hashem?’ those who held onto the Torah did not know Me” (Yirmiyahu 2:8).

“For My people are foolish; they have not known Me. They are stupid children, and they are not discerning” (ibid. 4:22).

“Hear this, you people who are stupid and without a mind. They have eyes, but cannot see; they have ears, but cannot hear” (ibid. 5:21).

As he did in his rebuke of Yehoyakim, Yirmiyahu identifies Bnei Yisrael’s refusal to know of God as the foundation of their immorality:

If only my head would be water and my eyes a spring of tears, so that I could cry all day and night for the slain of the daughter of my people! If only someone would give me a traveler’s lodge in the wilderness, then I would forsake my people and leave them, for they are all adulterers, a band of traitors. They draw their tongues, [but] their bow is falsehood. Not for good faith have they grown strong in the land, for they go forth from evil to evil, but Me they do not know – the word of Hashem. Let each man beware of his fellow; do not trust any kin! For every kinsman acts perversely and every acquaintance mongers slander. Each man mocks his fellow and they do not speak truth; they train their tongues to speak falsehood, striving to be iniquitous. Your dwelling is amid deceit; because of deceit they refuse to know Me – the word of Hashem. (Yirmiyahu 8:23-9:5)

Rashi (ibid. 9:5) explains “because of deceit they refuse to know Me,” writing: “they plot deceitfully, and they exchange their fear of Me for the sake of deceit, refusing to know Me.” In other words, knowledge of Hashem — defined at the end of this very prophecy as the emulation of Hashem’s ways of chesed, mishpat, and tzedakah — is antithetical to the rampant interpersonal deception that was endemic in the nation. If the people sought knowledge of Hashem, they would be forced to confront and renounce their evil ways. Instead, they took the easier way out, as Metzudas David explains: “because of their involvement in deceit, they refuse to know Me, for deception is easier than knowing Hashem.”

The Heritage of American Jewry

In my article, The Eleven Nations of America and the Seven Nations of Canaan, I cited the Doctrine of First Effective Settlement, a theory proposed in 1973 by Wilbur Zelinsky:

Whenever an empty territory undergoes settlement, or an earlier population is dislodged by invaders, the specific characteristics of the first group able to effect a viable, self-perpetuating society are of crucial significance for the later social and cultural geography of the area, no matter how tiny the initial band of settlers may have been … Thus, in terms of lasting impact, the activities of a few hundred, or even a few score, initial colonizers can mean much more for the cultural geography of a place than the contributions of tens of thousands of new immigrants a few generations later.

In this vein, Lopez is of the opinion that the sin of Columbus had a formative impact on the culture of the Americas which lasted long after the Age of Discovery. Here is a fuller excerpt from a passage I cited earlier:

I single out these episodes of depravity not so much to indict the Spanish as to make two points. First, this incursion, this harmful road into the “New World,” quickly became a ruthless, angry search for wealth. It set a tone in the Americas. The quest for personal possessions was to be, from the outset, a series of raids, irresponsible and criminal, a spree, in which an end to it — the slaves, the timber, the pearls, the fur, the precious ores, and, later, arable land, coal, oil, and iron ore — was never visible, in which an end to it had no meaning.

The assumption of an imperial right conferred by God, sanctioned by the state, and enforced by a militia, the assumption of unquestioned superiority over a resident people, based not on morality but on race and cultural comparison — or, let me say it plainly, on ignorance, on a fundamental illiteracy — the assumption that one is due wealth in North America, reverberates in the journals of people on the Oregon Trail, in the public speeches of nineteenth century industrialists, and in twentieth-century politics. You can hear it today in the rhetoric of timber barons in my home state of Oregon, standing before the last of the old-growth forest, irritated that anyone is saying “enough …, it is enough.”

What Columbus began, then, what Pizarro and Cortés and Coronado perpetuated, is not isolated in the past. We see a continuance in the present of this brutal, avaricious behavior, a profound abuse of the place during the course of centuries of demand for material wealth. We need only look for verification at the acid-burned forests of New Hampshire, at the cauterized soils of Iowa, or at the collapse of the San Joaquin Valley into caverns emptied of their fossil waters. (pp.9-11)

I am neither a prophet nor the son of a prophet. I cannot say which of our many iniquities are responsible for our present predicaments. But as American Jews, we are the de facto heirs to the cultural iniquities of America and Jewry. For this reason, it is reasonable to assume that the common sin identified by the writer from Oregon and the prophet from Anathoth persists in our culture today: the sin of “narrowly defining wealth,” the sin of exchanging the pursuit of knowledge for the pursuit of material success, and the sin of accumulating riches through oppression, extortion, and theft in defiance of chesed, mishpat, and tzedakah.

To be clear: the pursuit and enjoyment of wealth are not inherently evil, nor is there anything intrinsically wrong with enjoying the pleasures of the physical world. Yirmiyahu says this to Yehoyakim: “Behold, your father ate and drank, but practiced justice and righteousness – then it went well for him.” The Radak (ad loc.) explains:

In other words, I would not criticize you for your enjoyments if you were to do justice and righteousness, like your father, Yoshiyahu, who ate and drank like a king and enjoyed the good life — and since he did justice and righteousness, it went well for him, and he enjoyed the good for his whole life. But you enjoy the pleasures of this world in an evil manner, for you derive enjoyment from them not through uprightness and justice, but through extortion. Likewise, your food and drink and other pleasures come about through violence.

The same is true of modern capitalism which, like so many of mankind’s greatest innovations, is both a blessing and a curse, depending on how it is implemented, and towards what end.

Concluding Thoughts

Lopez concludes his remarks about Columbus with a message of hope:

The second point I wish to make is that this violent corruption needn’t define us. Looking back on the Spanish incursion, we can take the measure of the horror and assert that we will not be bound by it. We can say, yes, this happened, and we are ashamed. We can repudiate the greed. We recognize and condemn the evil. And we see how the harm has been perpetuated. But, five hundred years later, we intend to mean something else in the world.

The same is true for us: we need not be defined by the sins of our ancestors. Even though “our fathers sinned and are no more, and we bear their iniquities” (Eichah 5:7), we can do teshuvah for the iniquities we have inherited. This national teshuvah is the goal of every communal fast day, as the Rambam (Hilchos Taaniyos 5:1) codifies:

There are days on which all of Israel fasts because of the catastrophes that occurred on them, in order to awaken the hearts [of the people] and to open the paths of teshuvah (repentance). This will be a remembrance of our corrupt actions and the corrupt actions of our fathers that were like our actions today, which ultimately reached the point that [these corrupt actions] caused these catastrophes for them and for us. Through the remembrance of these things we will return to do good, as it stated, “they will confess their sins and the sins of their fathers” (Vayikra 26:40).

What does this mean on a practical level? I can’t say for sure because I don’t know. All I know is that this line of thinking should prompt us to ask questions of ourselves. What is our conception of wealth? How do we measure it? How do we accumulate it, and at what cost? How do we use it? To what extent is our relationship with wealth consistent with or contrary to the values of chesed, mishpat, and tzedakah? More importantly, how will we use our wealth to further our “knowledge of Hashem” as defined by Yirmiyahu? When will we make these changes, and what is holding us back from making them sooner?

I can think of no better way to conclude this article than with the eternal words of Yeshayahu (Chapter 58, haftarah of Shacharis Yom ha’Kippurim) about the type of fast that Hashem desires:

Cry out vociferously, do not restrain yourself; raise your voice like a shofar - proclaim to My people their willful sins, to the House of Jacob their transgressions. They [pretend to] seek Me every day and [pretend to] desire to know My ways, like a nation that acts righteously and has not forsaken the justice of its God; they inquire of Me about the laws of justice, as if they desire the nearness of God, [asking,] "Why did we fast and You did not see? Why did we afflict ourselves, and You did not know?"

Behold! On your fast day you seek out personal gain and you extort all your debts. Because you fast for grievance and strife, to strike [each other] with a wicked fist; you do not fast as befits this day, to make your voice heard above. Can such be a fast I choose, a day when man merely afflicts himself? Can it be merely bowing one's head like a bulrush and spreading sackcloth and ashes?

Surely this is the fast I choose: to break open the shackles of wickedness, to undo the bonds of injustice, and to let the oppressed go free, and to annul all perversion. Surely you should break your bread for the hungry, and bring the moaning poor [to your] home; when you see a naked person, clothe him; and do not hide yourself from your kin.

Then your light will burst out like the dawn and your healing will speedily sprout; your righteous deed will precede you and the glory of Hashem will gather you in. Then you will call and Hashem will respond; you will cry out and He will say, “Here I am!” If you remove from your midst perversion, finger-pointing, and evil speech, and offer your soul to the hungry and satisfy the afflicted soul; then your light will shine [even] in the darkness, and your deepest gloom will be like the noon. Then Hashem will guide you always, sate your soul in times of drought and strengthen your bones; and you will be like a well-watered garden and a spring of water whose waters never fail … then you will delight in Hashem, and I will mount you astride the heights of the world; I will provide you the heritage of your forefather Jacob, for the mouth of Hashem has spoken.

This Tishah b’Av, may we all fast in a manner that Hashem sees and responds in fulfillment of the prophetic words: “Tzion will be redeemed through justice, and those who return to her through righteousness” (Yeshayahu 1:26).

To repeat my disclaimer: This was an incredibly tricky article to write. I’ve worked it for so long that I can no longer tell whether it has any merit. Please let me know what you think — especially if you find it insightful on any level.

Like what you read? Give this article a “like” and share it with a friend! Dislike what you read? Share it anyway to spread the dislike!

Want access to my paid content without actually paying? If you successfully refer enough friends, you can get access to the paid tier for free!

Interested in reading more? Become a free subscriber, or upgrade to a paid subscription for the upcoming exclusive content!

If you've gained from what you've learned here, please consider contributing to my Patreon at www.patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss. Alternatively, if you would like to make a direct contribution to the "Rabbi Schneeweiss Torah Content Fund," my Venmo is @Matt-Schneeweiss, and my Zelle and PayPal are mattschneeweiss at gmail.com. Even a small contribution goes a long way to covering the costs of my podcasts, and will provide me with the financial freedom to produce even more Torah content for you.

If you would like to sponsor a day's or a week's worth of content, or if you are interested in enlisting my services as a teacher or tutor, you can reach me at rabbischneeweiss at gmail.com. Thank you to my listeners for listening, thank you to my readers for reading, and thank you to my supporters for supporting my efforts to make Torah ideas available and accessible to everyone.

-----

Substack: rabbischneeweiss.substack.com/

Patreon: patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss

YouTube: youtube.com/rabbischneeweiss

Instagram: instagram.com/rabbischneeweiss/

"The Stoic Jew" Podcast: thestoicjew.buzzsprout.com

"Machshavah Lab" Podcast: machshavahlab.buzzsprout.com

"The Mishlei Podcast": mishlei.buzzsprout.com

"Rambam Bekius" Podcast: rambambekius.buzzsprout.com

"The Tefilah Podcast": tefilah.buzzsprout.com

Old Blog: kolhaseridim.blogspot.com/

WhatsApp Group: https://chat.whatsapp.com/GEB1EPIAarsELfHWuI2k0H

Amazon Wishlist: amazon.com/hz/wishlist/ls/Y72CSP86S24W?ref_=wl_sharel

I find the point you and Lopez makes about how the initial founders strong desire for wealth at all costs and how it affects our culture today really poignant. I don't have any real data to back this up, but just by observation and being a part of it, I think our orthodox american community today is very materialistic and has an unhealthy relationship with wealth. Obviously desire for wealth is an age old desire, but it's interesting to think about just how privileged our frum community is today compared to generations past and if we're using our wealth in the right ways. Do we justify improper business practices, take advantage of 'price mistakes', and support corrupt economies and businesses - because hey I'm using my money to support torah and mitzvos? Thanks for bringing out this important message to think about before tisha bav and to inspire teshuva.

The Rav has a very interesting approach to the pesukim from Yirmiyahu you quoted about what one may glorify himself with in the context of the Haftarah on Tisha bAv (sorry for any typos, the scanning might have been a little off):

“The Haftarah on Tish'ah be-Av is not read like any other Haftarah on a holiday or even on a fast-day. The Haftarah on Tish'ah be-Av is actually the first kinah we say in the morning. The Haftarah speaks of urban and expresses utter despair and distress. We are to cry, to weep, and to mourn for the hurban Beit ha-Mikdash. And in order to do that, we first had to read Knot al pi nevrah. The reading of the Haftarah on Tish'ah be-Av is necessary as a formal license granted the mekonen and, by extension, us to weep and cry and ask questions of Ha-Kadosh Barukh Hu. 'The kinah of the Haftarah grants us the authority, the permission, to go on and say more knot and ask many questions like the questions Jeremiah asked the Ribbon shel Olam. This Kinah provided us with an example of the kinah we would be able to say in the generations to come. In a word, at night, Sefer Eikhah is the matir for Kinot; in the daytime, it is the Haftarah. As a matter of fact, as we have already noted, there normaly is a principle that we end a ritual recitation on a positive note. The Early Prophets concluded their works with words of praise and consolation" (Berakhot 31a). This means that a Haftarah must end with words of comfort, joy, and solace.

But we do not find this in the kinah that is the Haftarah of Tish'ah be-Av. "For death has come up into our windows, and has entered into our palaces, to cut off the children from outside, and the young men from the streets" (Jer. 9:20). Death visited our mansions and our homes to destroy children and young men. 'Speak thus; says the Lord, The carcasses of men shall fall as dung upon the open field, and as the handful after the reaper, and none shall gather them' (Jer. 9:21). These are not divrei nehamah, words of comfort and consolation. And then, at the end, we have two verses: "Thus says the Lord, Let not the wise man glory in his wisdom, nor let the mighty man glory in his might. But let him who glories glory in this, that he understands and knows Me" (Jer. 9:22-23). This too is not nehamah, or comfort. This is tokhahah, rebuke, an azharah, a warning! Tish'ah be-Av is an exception to the rule of ending with words of comfort because the navi that we read on that day is kinot. Even this privilege is taken away from us because we cannot be comforted "as long as our dead lies before us." The Haftarah is kinot, and after the Haftarah we continue directly with more kinot. There can be no divrei nehamah. The Haftarah is read during Shaharit, and the time for nehamah on Tish'ah be-Av begins later, after the conclusion of the reading of Knot. Kinot means utter despair, and that theme is introduced in the Haftarah.”

- "The Lord is Righteous in All His Ways" (pages 92-93)