Thoughts on the Seventh Morning

originally published as a Facebook note on the morning of 2/9/23

The Torah content for this week has been sponsored by Sarah and Moshe Eisen, with the following message: "Dedicated in honor of Popo, who shined bright and brought joy to so many of us. And to Rabbi Matt Schneeweiss who shared her with us and continues to share thoughts, insights, and Torah."

The Torah content for this week has also been sponsored by Nava, in memory of Adira Koffsky z"l, who loved learning and philosophy and was a real seeker of truth.

Thoughts on the Seventh Morning

Shivah for the grieving families ends today. (I say this somewhat loosely. It is true for the Koffsky and Bass families. The shivah for Martin Pepper's family has already ended in Israel. Shivah for Popo hasn't ended because it never started, since (a) she's not Jewish, and (b) we don't even know when the funeral will take place yet because of Hawaii's crazy mortuary delays.) Since halacha dictates that we limit our formal eulogizing of the deceased to the seven days of shivah (see Shulchan Aruch Yoreh Deah 394:1), I wanted to take this last opportunity to express some additional thoughts I had about Adira this morning. (click here for my eulogy of Adira)

Two passages jumped out at me this morning as I said my daily prayers. The first was the opening verses of Psalm 146: הַלְלוּ יָהּ הַלְלִי נַפְשִׁי אֶת י"י. אֲהַלְלָה י"י בְּחַיָּי אֲזַמְּרָה לֵאלֹהַי בְּעוֹדִי, which translates to: "Praise God, O my soul, praise Hashem. I will praise Hashem during my life; I will sing to my God while I am still alive." Alternative translations of the word בְּעוֹדִי in that second verse flitted through my mind: "I will sing to my God while I am still," "I will sing to my God in my stillness," "I will sing to my God in my evermore."

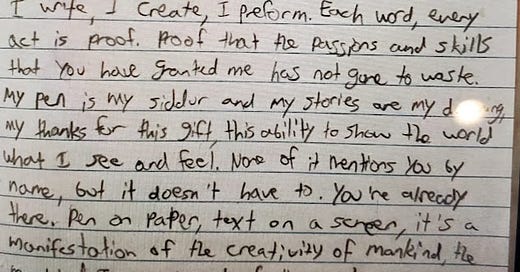

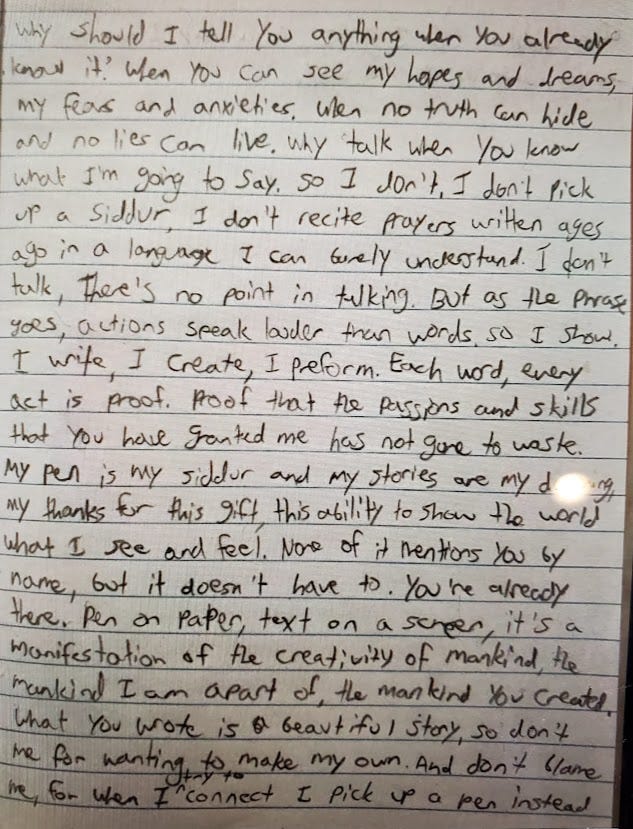

Adira sang to God while she was still alive, both literally and figuratively. I was reminded of a poem Adira's mother showed me at the shivah house. To my recollection, is the only personal statement I've ever read from Adira about her relationship with Hashem and her personal feelings about prayer. An excerpt of this poem was quoted in Dr. Goldstein's eulogy. Here is the poem in its entirety. I am told was written somewhat spontaneously - not in response to any prompt:

Why should I tell You anything when You already know it? When You can see my hopes and dreams, my fears and anxieties. When no truth can hide and no lies can live. Why talk when You know what I'm going to say. So I don't. I don't pick up a siddur. I don't recite prayers written ages ago in a language I can barely understand. I don't talk. There's no point in talking. But as the phrase goes, actions speak louder than words. So I show. I write, I create, I perform. Each word, every act is proof. Proof that the passions and skills that You have granted me has not gone to waste. My pen is my siddur and my stories are my davening, my thanks for this gift, this ability to show the world what I see and feel. None of it mentions You by name, but it doesn't have to. You're already there. Pen on paper, text on a screen, it's a manifestation of the creativity of mankind, the mankind I am a part of, the mankind You created. What You wrote is a beautiful story, so don't [blame] me for wanting to make my own. And don't blame me, for when I try to connect I pick up a pen instead of a siddur. Because I guess, in a way, I am talking to You, just in my own way.

Phrases from Adira's poem bring to mind verses from King David, our greatest poet. Adira's "Why should I tell You anything when You already know it?" recalls David's "O Hashem, You have scrutinized Me and You know. You know my sitting down and my rising up; You understand my thought from afar. You encompass my path and my repose, You are familiar with all my ways. For the word is not yet on my tongue - behold! Hashem, You knew it all" (Psalms 139:1-4).

Adira's "When no truth can hide and no lies can live" expresses the same sentiment as David's "Where can I go from Your spirit? And where can I flee from Your Presence? .... Would I say, 'Surely darkness will shadow me,' then the night would become as light around me. Even darkness obscures not from You; and night shines like the day; darkness and light are the same. For You have created my mind; You have covered me in my mother's womb" (ibid. 139:11-13).

Adira's "I don't talk. There's no point in talking" echoes David's "To You, O God, silence is praise" (ibid. 65:2). Adira's solution, "So I show. I write, I create, I perform. Each word, every act is proof" follows David's description of how the mute creation praises Hashem without speech: "The heavens declare the glory of God, and the firmament tells of His handiwork. Day following day utters speech, and night following night declares knowledge - [but] there is no speech and there are no words; their sound is not heard" (ibid. 19:2-4). The commentators (Radak, Meiri, and others) explain this in the same terms Adira used about herself: although none of the heavenly bodies "mention You by name," they "manifest [Your] creativity" through their actions, which "speak louder than words." Adira might have thought she was talking to Hashem in her own idiosyncratic way, but in truth, she was singing to Hashem like the stars in the sky.

Adira's statement, "None of it mentions You by name, but it doesn't have to. You're already there" bespeaks her recognition of Hashem's inescapable presence, as David wrote: "Where can I go from Your spirit? And where can I flee from Your Presence? If I ascend to heaven, You are there; were I to take up wings of dawn, were I to dwell in the distant west, there, too, Your hand would guide me, and Your right hand would grasp me" (ibid. 139:7-10).

Alas, Adira wrote "You can see my hopes and dreams, my fears and anxieties," and David declared: "When man's spirit departs, he returns to his earth; on that day his plans all perish" (ibid. 146:4). Seven days ago, Adira's spirit departed, and all her plans perished.

But she sang to God while she was still alive. She continues to sing to God in her stillness, forevermore.

The second passage that stood out to my mind this morning, as I gazed upon the pink and orange hue of the rising sun (and snapped a photo because it was just too beautiful not to capture), was the opening line of the first blessing of the Shema: "You, Hashem, are the Source of blessing, Who forms light and creates darkness, Who makes peace and creates all." This sentence, like the vast majority of the text of our prayers, was lifted from Scripture. In this case, however, the quotation is not verbatim. The original verse reads: "[Hashem said: I am the One] Who forms light and creates darkness; Who makes peace and creates evil; I am Hashem Who does all these things" (Isaiah 45:7). The Men of the Great Assembly, who formulated our prayers, opted for the lighter language of "creates ALL" rather than "creates EVIL." Perhaps - and this is pure speculation on my part - they did this because an explicit mention of God's relationship to the bad things that happen in the world would raise too many questions which the masses aren't ready to handle.

Admittedly, my mind went in that direction because I, myself, have been thinking for the past seven days about good and bad and God in relation to Adira's tragic death. In fact, I am planning to do what rabbis aren't supposed to do in situations like this: I'm planning to devote my Friday morning women's Jewish philosophy class to the topic of "dying before one's time" as explained by the Rambam and Ralbag.

I debated whether or not to give a class on such a sensitive topic, but I decided to go through it with for three reasons: (1) first and foremost, I am a teacher, and I need to teach this as part of my own grieving process; (2) these questions and problems exist, and will not go away just because we ignore them or avoid them; and (3) when I was at the shivah house of my student, Yehoshua, in Detroit this past Tuesday, I heard a rabbi give the grieving siblings the most inane explanations for how they should view the death of their mother - in the name of Torah, no less! - and although I held my tongue at the time, I feel like I need to do my part to "rebalance the universe" by putting some NON-inane ideas out there.

I'm not going to pretend that I have all the answers. As I would remind my students at the outset of my course on Sefer Iyov (the Book of Job), the Sages teach us that when Moshe spoke with Hashem "face to face," He asked the question of tzadik v'ra lo (a.k.a. "Why do bad things happen to good people?") If Moshe, the most perfected human being who ever lived, still asked this question at the height of his prophetic powers - and if he wrote the 42-chapter book of Iyov, which is one of the deepest and most difficult books in all of Tanach, to address this topic - then if anyone ever gives you a simplistic answer to the question of tzadik v'ra lo, then you can be 100% certain that it is wrong.

At the same time, if we withdraw our minds and avoid these difficult questions, then we are equally guilty. The Ramban discusses this attitude in Shaar ha'Gemul (3:41). After delving at length into the problem of tzadik v'ra lo, the Ramban concludes that although certain aspects of God's justice are concealed from us, we can be certain that everything He does is in accordance with righteousness, justice, kindness, and mercy. After arriving at this conclusion through the method of rational inquiry, Ramban anticipates his reader's objection:

And if you will object, saying: “Since certain aspects of God's justice are hidden from us, and since we are required to believe in His righteousness as the True Judge, why do you trouble us and exhort us to learn the rational arguments that you have explained and the abstract ideas to which you have alluded? Why can't we throw all of this behind us and rely, as we ultimately must, on the belief that there is no iniquity or forgetfulness before Him, but that all of His ways are Just?"

Ramban's response is harsh:

This is an objection of fools who despise wisdom (ksilim moasei chochmah). The answer is that we benefit ourselves through the aforementioned learning and become wise individuals who know God by way of His conduct and actions. Furthermore, we will have even more conviction (emunah) and trust in God (bitachon) than those who do not pursue rational inquiry, in both the known and the hidden aspects of God's justice. It is the obligation of every created being, who serves [God] out of love and awe, to investigate with his mind to confirm the righteousness of His justice and to verify His judgment according to one's ability. The approach we have taken is the approach of those who are wise: to bring our minds in line with ideas and to rationally verify the Creator's judgments.

That is the spirit with which I intend to take up these questions in my classes on such topics - not in the vain attempt to arrive at complete answers, but in order to understand God's justice to the extent that I can, and to avoid falling prey to the malady characteristic of "fools who despise wisdom."

Sadly, Adira never had the opportunity to learn Iyov with me. I know she would have reveled in the discussions and relished the ideas. Tragic as her death was, I am happy that she spent these last months of her life at Midreshet Amudim - an environment that allowed her to search for answers and provided her with the tools and personal development to discover such answers on her own.

I am going to dedicate Friday's shiur to Adira's memory - NOT to "give her neshamah an aliyah" (which, as I taught Adira myself, is a notion that the Rambam would reject as wishful thinking), but because she, like Ramban, had no pity for fools who despite wisdom or give childish answers to weighty philosophical conundrums. She would have pursued rational answers to these questions with single-minded zeal, rejecting foolishness and fluff in all its forms.

At the very end of Sefer Iyov, after Iyov acknowledges the truth, repents, and renounces his words of blasphemy, what does Hashem do? He blesses Iyov and rebukes Iyov's friends - Eliphaz, Bildad, and Tzofar, who gave "religious" answers to the question of tzadik v'ra lo. Hashem tells Eliphaz: "My wrath blazes against you and against your two friends, for you did not speak properly about Me as My servant Iyov did" (Iyov 42:7). In other words, while Iyov is the one who said and believed heretical notions on account of his suffering, he was honest in his inquiry and refused to accept the stupidity espoused by his religious friends. That is the type of person who truly serves Hashem: the one who seeks truth with an honest mind - not those who suppress their doubts and paper them over with trite dogmas.

Adira, like Iyov, may have held or uttered beliefs which did not conform with traditional Jewish doctrines. But it was clear to everyone who knew her that her mind searched for truth and clarity, and that is what is considered "speaking properly about Hashem." Adira was still at an early stage of the process of trying to figure out her Judaism, her relationship with Hashem, and herself. But I am absolutely convinced that she was on the right path. Last night I gave a shiur on the Sefer ha'Ikkarim (4:17) who said that Hashem only listens to the prayers of those whose emotions are in line with their rational faculty. Even though Adira spoke with Hashem in her own way, He most definitely listened.

May Adira's soul - and as well as the souls of Popo, Julie Bass, and Martin Pepper - be bound up in the bundle of life, in the World to Come.