Vayechi: How Never to Be Angry at Anyone or Hate Anyone (Part 1: Questions)

Yes, this is the second week in a row that I've written a "questions only" article. Unlike last time, I plan on writing Part 2 (for paid subscribers). I published this today because I'll be traveling.

It’s a new year on the Gregorian calendar, a new year of my life (I turn 41 on January 10th), and a new opportunity for sponsorships! I currently don’t have any sponsorships lined up for 2025, so I’d like to try an experiment: for every week you sponsor, I’ll include a free month of paid subscriber access to the Rabbi Schneeweiss Substack! If you’ve been curious about my writing that’s too controversial, too personal, or too speculative to publish publicly, this is a great way to gain access while supporting my Torah endeavors!

Click here for a printer-friendly version of this article.

Vayechi: How Never to Be Angry at Anyone or Hate Anyone (Part 1: Questions)

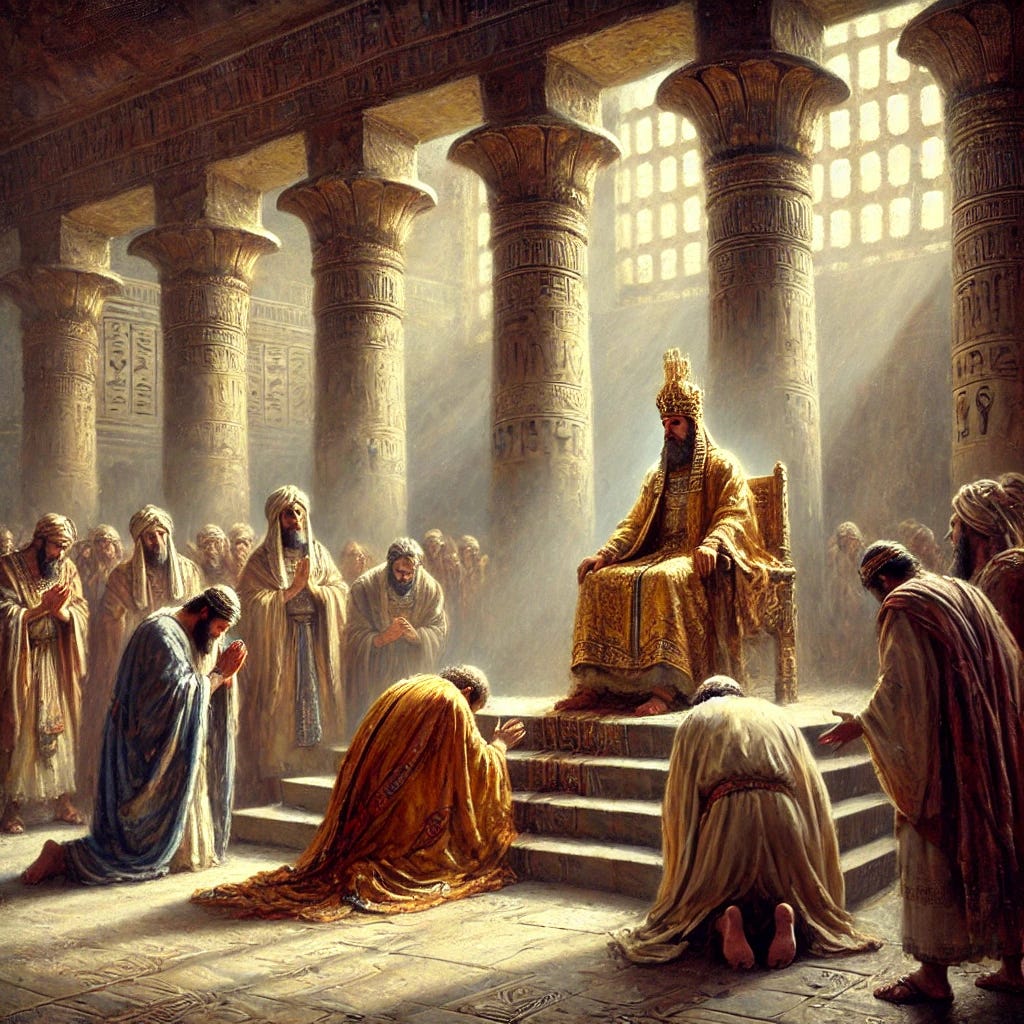

The saga of Yosef and his brothers concludes with a poignant interaction after the death of Yaakov Avinu:

Yosef’s brothers, having seen that their father was dead, thought, “It could be that Yosef might retain hatred for us, and might wish to repay us all the evil that we have done him.” They then caused it to be said to Yosef, “Your father commanded before he died, saying: ‘Thus shall you say to Yosef, “Please pardon, I pray, the fault of your brothers and their deficiency, for they have treated you ill”’; and now pardon, please, the fault of the servants of your father’s God.” And Yosef wept when they spoke to him. (Bereishis 50:15-17)

Shadal renders [1] the phrase “vaytzavu el Yosef” as “they then caused it to be said to Yosef” through intermediaries. He clarifies which statements were attributed to Yaakov and which belonged to the brothers:

and now pardon, please. These are not part of the words attributed to Yaakov. Rather, the Egyptian messengers, after telling Yosef the dead man’s words as if Yaakov himself had spoken to them before his death – commanding them to say to Yosef, “Please pardon, I pray, the fault of your brothers and their deficiency, for they have treated you ill” – added on their own, “And now pardon, please, the fault of the servants of your father’s God” (Dubno).

Of course, this was a fabrication: Yaakov had never instructed Yosef to forgive his brothers. The brothers were so fearful of Yosef’s anger that they felt compelled to concoct this story to secure his forgiveness. Shadal (ibid.) explains why the Egyptian messengers added the strange phrase, “the servants of your father’s God” to convey the brothers’ plea:

[The message was couched in these terms] because the fact that they were Yosef’s brothers would not have sufficed for them to gain his pardon, for they had not behaved toward him like brothers. Therefore, the messengers mentioned another kind of love that the brothers had in common with him, that is, that they were his co-religionists. The Egyptians held their co-religionists in esteem but despised members of other faiths; thus, they were likely to pardon the faults of their co-religionists. The messengers thought that Yosef, too, would act this way and forgive members of his own faith, even if they were not worthy to be called his brothers.

Imagine how estranged a sibling must feel to be unable to plead, “Forgive me because I’m your brother!” and instead have to say, “Forgive me as a fellow Jew!” That is how utterly hopeless Yosef’s brothers felt about obtaining his forgiveness. This moved Yosef to tears, as Shadal explains:

and Yosef wept. He understood that it was his brothers who had sent the messengers and told them what to say, and that Yaakov had not commanded any of this, for if it had been Yaakov’s intention to command it, he would have told Yosef or sent word before his death. Therefore, he wept when he saw the distress of his brothers, who were afraid for their lives and who had been forced to fabricate stratagems to save themselves from his wrath.

What did the brothers do upon hearing about Yosef’s reaction? The Torah tells us: “Then his brothers themselves went, cast themselves down before him, and said, ‘Here we are your slaves’” (ibid. 50:18). Shadal explains:

Then his brothers themselves went. When they heard that Yosef had wept and not become angry with them or expressed a wish to take revenge upon them – and they understood that he had seen through their ruse – they quickly went to him and prostrated themselves before him, in order to make it clear that they were subservient to him, and to be sure of his good will toward them.

In other words, they still did not trust that Yosef had truly forgiven them, and they hastened to demonstrate their utter subordination to him, hoping for any sign that their teshuvah had been accepted. Yosef gives them that sign:

But Yosef said to them, “Do not be afraid, for do I perhaps act as God [to be able to punish intentions]? If you had the thought of doing me ill, God willed for good, to bring about that which has happened, to keep alive many people. Now, then, do not be afraid; I will feed you and your children.” Thus he consoled them and spoke to their heart. (ibid. 50:19-21).

Shadal expands upon Yosef’s words, explicating the sentiments he intended to convey to his brothers:

"The Holy One, blessed is He, investigates the hearts and judges humankind not only according to their actions, but also according to their thoughts, while a human judge has only what his eyes see. I, too, can judge you not on your intentions, but only on your actions. If you intended me ill, your intention was not fulfilled, but God’s was, and that was for good. You have no need to lower yourselves before me and plead for forgiveness, for I see in you only the agents of Providence working for the benefit of many people.”

Shadal then draws a takeaway lesson from Yosef’s words and conduct:

Now this is one of the great benefits that flow from faith in God and His Providence, for although man is master over his own deeds, the completion of any action is not in his hands, but in Heaven's (see my comment on Vayikra 21:7). If a wicked man schemes against a righteous man and seeks to harm him, God will not leave it in his hands, but the wicked man's very hatred will be the cause of the righteous man's prosperity. One who embraces this belief will never be angry at anyone or hate anyone.

Here is Shadal’s commentary on Vayikra 21:7:

Since the verse “It is of the Lord that a man’s footsteps are established though he desires his way [ve-darko yeḥpats]” (Tehilim 37:23) has come to our attention, I will express my opinion about it, for in my view, its meaning is quite simple, yet the commentators have gone far afield. I think the meaning of this verse is exactly the same as that which is written in Mishlei 16:9, “A man’s heart devises his way; but the Lord directs his steps.” The phrase here, ve-darko yeḥpats, corresponds to “A man’s heart devises his way [lev adam yeḥashev darko]” … The meaning is that man is a master of free will, and he is the one who desires and chooses his own way and who devises in his heart what he will do, but the completion of his action does not depend on his own power, but is in the hand of Heaven, for “it is of the Lord that a man’s footsteps are established.” If the way that he is going is not correct in the eyes of the Lord, his footsteps will not be established, and he will be unable to complete his way and fulfill his devisings.

Shadal makes an alluring promise: if one “embraces this belief” that “although man is master over his own deeds, the completion of any action is not in his hands, but in Heaven’s,” then they “will never be angry at anyone or hate anyone.” The question is: How does this work? Can this belief really spare us all interpersonal animosity?

There’s another problem: in his commentary on the verse in Bereishis, Shadal claims that “If a wicked man schemes against a righteous man and seeks to harm him, God will not leave it in his hands, but the wicked man’s very hatred will be the cause of the righteous man’s prosperity.” This statement appears to apply exclusively to those who are righteous, like Yosef. However, in his commentary on Vayikra 21:7, he writes that “If the way that he is going is not correct in the eyes of the Lord, his footsteps will not be established, and he will be unable to complete his way and fulfill his devisings” – a statement which seems to apply to anyone, regardless of their righteousness. Which is it? If Shadal’s statement is limited to the righteous, how does it help the rest of us?

I don’t feel confident enough in my understanding of Shadal’s views on hashgachah (Divine providence) to answer on his behalf. I do, however, have some speculative thoughts of my own, which I’ll share in a paid subscriber post.

[1] The English translations of the verses cited in this article are by Dan Klein, based on Shadal’s Italian translation of the Chumash (Pentateuco). Any bracketed text in these verses comes from Shadal himself. The translation of Shadal’s commentary is also by Klein, though the bracketed text within the commentary is Klein’s own. I have made two additional modifications for consistency in my Substack: (1) I use Hebrew names instead of English (e.g., “Yosef” instead of “Joseph,” “Mishlei” instead of “Proverbs). (2) I have bolded some text for emphasis.

Let me know what you think!

Like what you read? Give this article a “like” and share it with someone who might appreciate it!

Want access to my paid content without actually paying? If you successfully refer enough friends, you can get access to the paid tier for free!

Interested in reading more? Become a free subscriber, or upgrade to a paid subscription for the upcoming exclusive content!

If you've gained from what you've learned here, please consider contributing to my Patreon at www.patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss. Alternatively, if you would like to make a direct contribution to the "Rabbi Schneeweiss Torah Content Fund," my Venmo is @Matt-Schneeweiss, and my Zelle and PayPal are mattschneeweiss at gmail. Even a small contribution goes a long way to covering the costs of my podcasts, and will provide me with the financial freedom to produce even more Torah content for you.

If you would like to sponsor a day's or a week's worth of content, or if you are interested in enlisting my services as a teacher or tutor. Thank you to my listeners for listening, thank you to my readers for reading, and thank you to my supporters for supporting my efforts to make Torah ideas available and accessible to everyone.

-----

Substack: rabbischneeweiss.substack.com/

Patreon: patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss

YouTube: youtube.com/rabbischneeweiss

Instagram: instagram.com/rabbischneeweiss/

"The Stoic Jew" Podcast: thestoicjew.buzzsprout.com

"Machshavah Lab" Podcast: machshavahlab.buzzsprout.com

"The Mishlei Podcast": mishlei.buzzsprout.com

"Rambam Bekius" Podcast: rambambekius.buzzsprout.com

"The Tefilah Podcast": tefilah.buzzsprout.com

Old Blog: kolhaseridim.blogspot.com/

WhatsApp Content Hub (where I post all my content and announce my public classes): https://chat.whatsapp.com/GEB1EPIAarsELfHWuI2k0H

Amazon Wishlist: amazon.com/hz/wishlist/ls/Y72CSP86S24W?ref_=wl_sharel

This seems to be related to your recent post regarding the scope of the attribution of the brother's sale of Yosef to God.

Off the bat, I would say that Shadal means righteous vis a vis the particular harm someone seeks to inflict on them.

His position seems to align with that espoused by Chovos hal'vovos (Sha'ar habitachon) and Chinuch (421) that a person cannot harm or benefit another unless the fellow has it coming due to sin or earned via meritorious behavior.

Personally, I've always had a hard time with that approach and am somewhat taken aback to see Shadal's apparent embrace of it.