Ki Tisa – “Please Erase Me From Your Book”

What was Moshe thinking when he asked Hashem to erase him from His book? I began writing an article, based on Sforno, which turned into 90% of a written shiur. I hope you still find it insightful!

This week's Torah content has been sponsored by Jonah Mishaan with appreciation for Rabbi Schneeweiss, who gathers wisdom from various disciplines.

Shlomo HaMelech highlights the importance of mental health in Mishlei 18:14: "The spirit of a person sustains him in his illness, but who can lift a broken spirit?" My rebbi, Rabbi Moskowitz zt"l, emphasized that while a person can accomplish much on their own, there comes a point when one should seek professional help. Jonah is a psychotherapist who offers services in person in Upper Manhattan and virtually. For more information, visit his website at mishaanpsychotherapy.com.

Click here for a printer-friendly version of this article.

Ki Tisa – “Please Erase Me From Your Book”

The day after the Sin of the Golden Calf, Moshe Rabbeinu makes a startling statement:

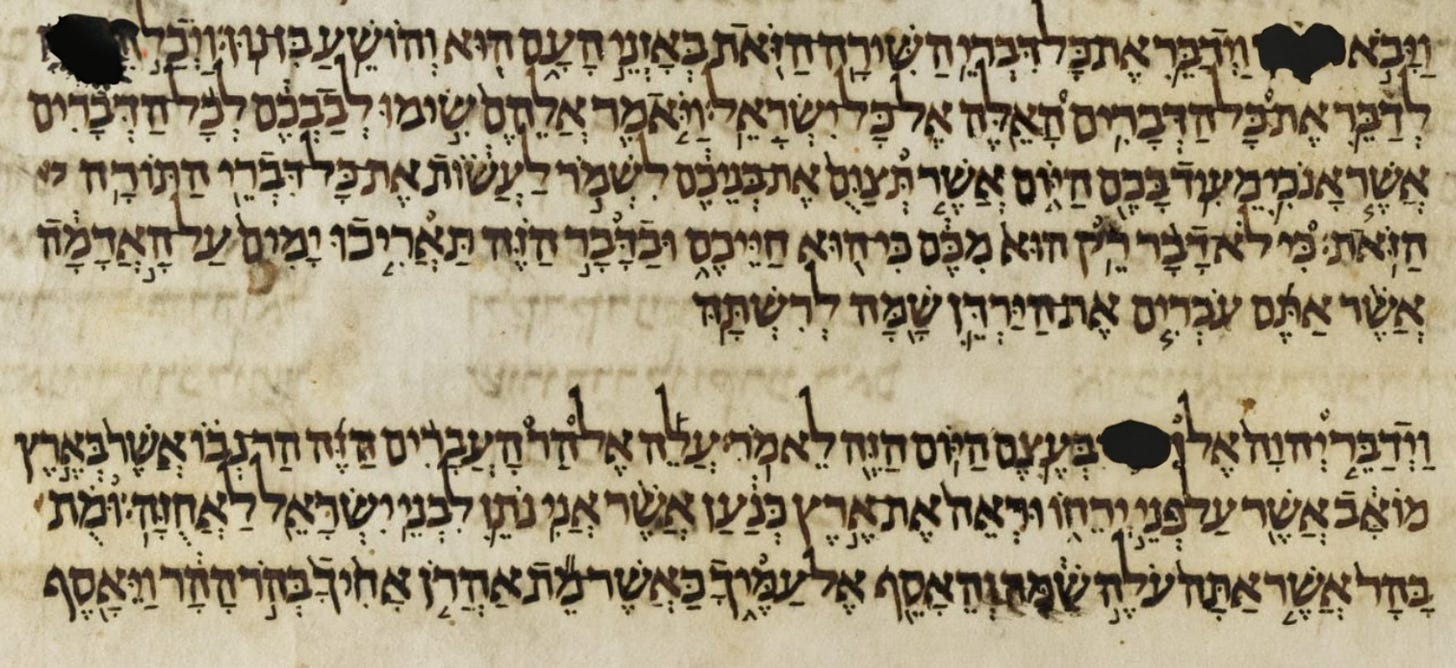

(30) The next day, Moshe said to the people, "You have sinned a great sin, and now let me go up to Hashem; perhaps I can gain atonement for your sin." (31) Moshe returned to Hashem and said, “Please, this people has sinned a great sin, and they have made for themselves a god of gold. (32) And now, if You forgive their sin–, and if not, erase me, please, from Your book which You have written.” (33) Hashem said to Moshe, “He who has sinned against Me, I will erase from My book. (34) And now, go lead the people to where I have spoken to you. Behold My angel will go before you; but on the day that I have a reckoning, I will reckon to them their sin.” (Shemos 32:30-34)

Before we delve into the problem of Moshe’s petition, we need to address three ambiguities in the text: (1) the elliptical phrase, “And now, if you forgive their sin –” (2) the identity of “Your book which You have written,” and (3) the punctuation of Hashem’s response. Our analysis will follow Sforno’s commentary. Since readers are likely to be more familiar with Rashi’s reading (above), we will address these ambiguities using Rashi as a foil to Sforno.

(1) Rashi (ibid. 32:32) treats this as a mikra katzar (truncated verse), reading it as: “if You forgive their sin, [then all is good] – but if not, please erase me from Your book which You have written.” In contrast, Sforno (ibid.) translates this elliptical phrase as: “whether or not You forgive their sin, please erase me from Your book which You have written.” In other words, Moshe was not presenting a set of alternative choices nor was he stating an ultimatum; he was making an unqualified request to be erased.

(2) Whereas Rashi (ibid.) explains that Moshe was asking to be erased “from the entire Torah, so that people should not say about me that I was not worthy enough to pray effectively for them,” Sforno (ibid.) understands “Your book which You have written” as a reference to the allegorical “book of records,” in which God records our merits and iniquities to mete out reward and punishment. Chazal employ this metaphor frequently, for example: “all your deeds are written in a book” (Avos 2:1) and “the ledger is open and the hand records” (ibid. 3:16).

(3) Rashi doesn’t comment on Hashem’s answer, but presumably, he reads this as a negative response to Moshe’s question: “[No!] He who has sinned against Me, I will erase from My book.” Sforno (ibid. 32:33), however, reads it as a rhetorical question: “Who is there that sinned against Me that I should erase him from My book? [Nobody!]”

The question is: What was Moshe asking for and what did Hashem mean in His response? Sforno explains:

(32) whether You agree to forgive (lit. “lift” or “bear”) their sin or You do not agree to forgive (“lift” or “bear”), erase my merits from Your book and add [them] to their account (cheshbone) so that they will merit forgiveness. (33) Who is there that sinned against Me that I should erase his merits from My book so that he shall merit a corresponding forgiveness for [their] sins?! This is impossible, for this is contrary to Divine justice. Indeed, each person must bear the punishment for his own iniquity and receive reward for his own merits, since “a mitzvah cannot extinguish an aveirah (transgression)” (Sotah 21a). I certainly will not add your merits to their account!

Hashem’s response makes perfect sense: Divine justice dictates that Hashem rewards each person for their own merits and punishes each person for their own sins. The alternative would be unjust and would likely raise the objection from Avraham Avinu: “God forbid! Will the Judge of the whole earth not do justice?!” (Bereishis 18:25).

Not only does Hashem’s response make sense, but it is (arguably) the primary source for Judaism’s stance on Divine justice. Out of the many references to reward and punishment in the Torah, the Rambam (Introduction to Chelek) cites Hashem’s response to Moshe’s question as the Scriptural source for this fundamental principle:

The eleventh fundamental principle is that He rewards with good those who fulfill the commandments of the Torah and punishes the one who transgresses its admonitions … The verse which points to this fundamental principle is that which is stated, “And now, if You forgive their sin–, and if not, erase me, please, from Your book which You have written.” and He, may He be exalted, responded, “He who has sinned against Me, I will erase from My book” – a proof that the one who serves Him and the sinner are both known before Him, to pay good reward to this one and to punish this one.

The problem does not lie in Hashem’s response, but in Moshe’s request. What was Moshe thinking?! Reward and punishment is not a point system! The notion of vicarious merit is as unjust as the notion of vicarious punishment. Of course Hashem wouldn’t be willing to transfer the merits of a tzadik to the “account” of a sinner so that the latter might attain forgiveness. That would be unjust! How can we understand what Moshe was asking for?

I believe the answer is embedded in Sforno’s commentary, but we’re going to need to do some work to tease it out. Here is his commentary once again, with a greater focus on the Hebrew and a different emphasis in bold:

(32) whether You agree to forgive their sin (nosei chatasam, lit. “lift” or “bear,” from the root נ.ש.א.) or You do not agree to forgive (laseis, lit. “lift” or “bear,” from נ.ש.א.), erase my merits from Your book and add [them] to their account so that they will merit forgiveness (selichah, from ס.ל.ח.). (33) Who is there that sinned against Me that I should erase his merits from My book so that he shall merit corresponding forgiveness (selichah) for [their] sins?! This is impossible, for this is contrary to Divine justice. Indeed, each person must bear (nosei, from נ.ש.א.) the punishment for his own iniquity and receive reward for his own merits, since “a mitzvah cannot extinguish an aveirah.” I certainly will not add your merits to their account!

There are two concepts at play here, expressed by two terms: nesius ha’cheit (נ.ש.א., “lifting” or “bearing” the sin) and selichas ha’cheit (ס.ל.ח., “forgiving” or “pardoning” the sin). If we were left to our own devices, it would be difficult to discern the meaning and implications of Sforno’s words. Thankfully, Sforno had a student, R’ Elia di Nola, who took notes on his teacher’s shiurim (lessons). These notes were recently published by Rabbi Moshé Kravetz, who graciously made them available on AlHaTorah. Here are R’ Elia’s notes (ibid.) on Sforno’s approach:

and now let me go up to Hashem; perhaps I can gain atonement for your sin – I do not hope for selichah (forgiveness) but for kaparah (atonement), because kipur (atonement) is not mechilah (forgiveness) but rather the alleviation and minimization of the iniquity, as it is written: “[the kohen] shall atone for him and he will be forgiven” (Vayikra 4:31) – thus, [we see that] atonement is not forgiveness.

Likewise, Moshe Rabbeinu said to Ha’Kadosh Baruch Hu in this language: “Please, this people has sinned a great sin” and specified the sin. “And now, whether or not You bear their sin, please erase me from Your book that You have written” – in other words, whether or not You bear their sin, erase me from the merits of Your book which you have written, for “if You will bear,” along with the erasure of my merits, this will result in a complete selichah, for “bearing” is not complete selichah but only a lightening of the punishment. “and if You do not bear” [means:] erase my merits and consider their sin against that [measure of merit], and erase from their sin the portion corresponding to all my merits.

Hashem said, “Who is there that sinned against Me that I should erase him from My book?!” – [this should be read as] a rhetorical question, as if to say: “Who is the one who sinned? Even with regards to that individual, I will not erase him from My book, for “a mitzvah doesn’t extinguish an aveirah” – all the more so from one person to another. Only the soul that sins will die, for thus is the Divine justice established.

R’ Elia clarifies two points. First, there is a difference between forgiveness (selichah in Biblical Hebrew, or mechilah in Rabbinic Hebrew), which refers to the removal of the sin, and atonement (kaparah) or “bearing/lifting” (nesius), which refers to the alleviation and minimization of the sin (see Sforno on Vayikra 16:30). Second, Moshe was not asking for his merits to be transferred directly to the accounts of the Israelites to secure an automatic selichah for them; rather, his hope was that if Hashem were to “bear” the sins of Israel along with the erasure of his own merits, that combination would result in a complete selichah.

But this is still far from comprehensible. What, exactly, was Moshe proposing? What would it mean for Hashem to erase his merits? How would this erasure, combined with Hashem “bearing” of their sin, result in a complete seilchah for them? What exactly did Moshe mean (according to R’ Elia) when he said: “erase my merits and consider their sin against that [measure of merit], and erase from their sin the portion corresponding to all my merits”? What kind of metaphysical accounting is this? And, at the end of day, how did Moshe reconcile this with Divine justice, by which each person is punished for their own iniquities and rewarded for their own merits?

I owe an additional debt of gratitude to R’ Kravetz for his extensive annotations, without which I would not have thought to look at R’ Elia di Nola’s commentary on Tehilim 32:1. There, he provides a critical piece of the puzzle:

Furthermore, you should know that the word nosei is not selichah, but rather, the toleration of the sin [by delaying] punishment for another generation, as Moshe said: “and now, if you will tolerate their sin” (Shemos 32:32), and He answered: I will do as you say, “and on that day I have a reckoning, I will reckon to them their sin (ibid. 32:34).

This opens a path to understanding. If nesius ha’cheit refers to the deferment of the punishment for another generation, then Moshe’s proposal can be reframed as follows: “if You are willing to be nosei avon (i.e. to tolerate their iniquity) for another generation AND if You are willing transfer a proportionate amount of my merits” – whatever that means – “then there is hope that they’ll do teshuvah and attain complete selichah.” In other words, Moshe is not asking to trade off his own merits for their selichah. Rather, he’s asking that his merits be “used up” – again, whatever that means – in order to delay the Israelites’ punishment, giving them enough time to do teshuvah and merit selichah by their own efforts. This proposition is not contrary to Divine justice!

This hidden gem from R’ Elia yields another important clue: apparently, the “reckoning” verse after Hashem’s refusal to erase Moshe from His book is part of Hashem’s response. Here’s Sforno’s commentary on that verse:

and on the day when I have a reckoning … when they will continue to sin, as [for example] in [the Sin of] the Spies, I will reckon to them their sin … [that is,] this sin [of the Golden Calf] – and I will no longer continue to overlook it, similar to, “but if wickedness shall be found in him, he shall die” (I Melachim 1:52). And so He indicated when He said there [at the Sin of the Spies]: “How long will this people despise Me?” (Bamidbar 14:11), for since they have repeated their folly, they are certain to continue incurring guilt, as our Sages stated: “When a man transgresses and repeats his offense, it becomes permitted to him – that is, it becomes as if it were permitted” (based on Yoma 86b).

Before we factor this into our analysis, here are R’ Elia’s additional notes on the same verse:

And now, go lead the people etc. but on the day that I have a reckoning, I will reckon to them their sin. [This means] that I will not “annihilate them,” as I said; rather, I will punish them “on the day of My reckoning.” Likewise, the Sages said: “There is no iniquity of Israel that doesn’t contain a litra (small amount) of [the Sin of the Golden] Calf” (Sanhedrin 102a).

And this second tefilah [in which Moshe asked for Israel’s sin to be tolerated and for his merits to be erased and added to their account] was effective in helping the beinonim (the “middling” Jews, whose involvement in the sin was neither fully wicked nor righteous) not to be annihilated. Regarding the tzadikim (righteous), it was said [earlier, immediately after Hashem informed him of the Calf and Moshe prayed for their forgiveness]: “Hashem relented from the harm that He said He would do to His people” (Shemos 32:14). The resha’im (wicked people) who made the Calf died immediately: some in the plague, some by the sword of their brethren, and some by being forced to drink the water, for there were levels among them as well …

Yet another important point emerges from these commentaries. Contrary to our initial reading, Moshe did not receive an unequivocal “No!” as an answer to his request. Rather, Hashem rejected the specific method that Moshe proposed – combining the erasure of his merits with the deferment of Israel’s punishment so that they could eventually attain seilchah through teshuvah – but Moshe’s tefilah “was effective in helping the beinonim.” Hashem accepted Moshe’s request to delay their punishment, saying that He would not “annihilate them,” but instead, would punish them “on the day of their reckoning” in the future.

This tefilah was specifically on behalf of the beinonim, since the tzadikim had already been saved and the resha’im had already been destroyed. Thanks to Moshe, the punishment of these beinonim would be held in suspension: if they did teshuvah, as Moshe hoped, they would be forgiven, but if they continued to sin, then Hashem’s punishment for those subsequent sins would be increased on account of the Sin of the Calf. Tragically, this is exactly what happened with the Sin of the Spies, and this time, Hashem did not forgive them, but instead decreed: “In this wilderness they shall cease to be, and there shall they die” (Bamidbar 14:35).

Now that we understand the ultimate result of Moshe’s tefilah, we can reverse engineer his original request. What was Moshe proposing when said: “erase my merits from Your book and add [them] to their account so that they will merit forgiveness”? Here is my current take which is 90% worked out at the time of publication.

According to the Rambam (see Shemoneh Perakim Chapters 2 and 7 and Hilchos Teshuvah 3), “merits” refer to a person’s intellectual and ethical virtues. Without putting forth his request, Moshe would have gone on to lead the surviving tzadikim through the Wilderness into the Land of Israel. Because they were tzadikim, Moshe’s merits (i.e. his virtues) would have been utilized “in full” during the remainder of his mission. He would have taught them Torah, accustomed them to mitzvos, and prepared them to conquer and settle the Land – utilizing all of his perfection and leadership to train up this “kingdom of priests and a holy people” (Shemos 19:6).

But Moshe wasn’t satisfied with that. He wanted to save the beinonim as well. Moshe knew that the only way to do this would be to “expend” his own virtues on the effort to facilitate their long teshuvah process while simultaneously handling the increased burden of leadership. He expressed this as an “erasure” of his virtues because, effectively, that’s what would need to happen for this plan to work. Consider the following loose analogy: If Oppenheimer had been tasked with leading a small team of top-tier physicists on the Manhattan Project, his "merit" as a physicist would have been fully utilized. However, if thousands of college-aged physics majors were added to that team, and Oppie was expected to accomplish his original mission while also monitoring and mentoring these less-capable newcomers, his "merit" as a physicist would necessarily be diminished with the time and energy spent catering to their needs and making accommodations for their lower level of expertise.

This is an example of Moshe’s selflessness. He could have allowed Hashem to purge the nation of all but the cream of the crop. Instead, he volunteered to relinquish the higher role he could have taken as a leader of the elite so that he could help rehabilitate the mediocre masses, bearing them “like a nurse carries a baby” (Bamidbar 11:12).

If this explanation is correct, then what did Hashem mean when He rejected the first part of Moshe’s plan, saying, “Who is there that sinned against Me that I should erase him from My book?” I don’t know! That is a question for you to think about over Shabbos, and for me to tackle in a future article or shiur.

What do you think of the Sforno’s approach, or my explanation of it? Any ideas about how to answer the question we left off with? I’d love to hear your thoughts!

Like what you read? Give this article a “like” and share it with someone who might appreciate it!

Want access to my paid content without actually paying? If you successfully refer enough friends, you can get access to the paid tier for free!

Interested in reading more? Become a free subscriber, or upgrade to a paid subscription for the upcoming exclusive content!

If you've gained from what you've learned here, please consider contributing to my Patreon at www.patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss. Alternatively, if you would like to make a direct contribution to the "Rabbi Schneeweiss Torah Content Fund," my Venmo is @Matt-Schneeweiss, and my Zelle and PayPal are mattschneeweiss at gmail. Even a small contribution goes a long way to covering the costs of my podcasts, and will provide me with the financial freedom to produce even more Torah content for you.

If you would like to sponsor a day's or a week's worth of content, or if you are interested in enlisting my services as a teacher or tutor. Thank you to my listeners for listening, thank you to my readers for reading, and thank you to my supporters for supporting my efforts to make Torah ideas available and accessible to everyone.

-----

Substack: rabbischneeweiss.substack.com/

Patreon: patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss

YouTube: youtube.com/rabbischneeweiss

Instagram: instagram.com/rabbischneeweiss/

"The Stoic Jew" Podcast: thestoicjew.buzzsprout.com

"Machshavah Lab" Podcast: machshavahlab.buzzsprout.com

"The Mishlei Podcast": mishlei.buzzsprout.com

"Rambam Bekius" Podcast: rambambekius.buzzsprout.com

"The Tefilah Podcast": tefilah.buzzsprout.com

Old Blog: kolhaseridim.blogspot.com/

WhatsApp Content Hub (where I post all my content and announce my public classes): https://chat.whatsapp.com/GEB1EPIAarsELfHWuI2k0H

Amazon Wishlist: amazon.com/hz/wishlist/ls/Y72CSP86S24W?ref_=wl_sharel

Perhaps something like this:

Hashem says to Moshe that even if you diminish your merit that doesn't make you a sinner and you still have a place in the book. Or, I prefer this one, Moshe's willingness to diminish himself in order to save more people is actually a credit to him and increases his merit rather than detract from it.

So I read this over Shabbat and it seems based on the explanation given that Hashem's response was His way of accepting Moshe's proposition.