Ki Tisa: Shadal’s Anti-Rationalist Rational Explanation of Ayin ha’Ra (the Evil Eye)

What if I told you there’s an explanation of ayin ha’ra that is neither purely rationalistic nor mystical? True to form, Shadal offers just such an explanation.

The Torah content for this week has been sponsored by my friend, Rabbi Dr. Elie Feder. His latest book, Happiness in the Face of Adversity: Powerful Torah Ideas from a Mom's Parting Words, shares the wisdom of Shani Feder a"h, a true Eishes Chayil. This is the kind of Torah I wish more people knew—ideas that directly impact our experience of life. Available now on Amazon.

Click here for a printer-friendly version of this article.

Ki Tisa: Shadal’s Anti-Rationalist Rational Explanation of Ayin ha’Ra (the Evil Eye)

One of the many reasons I love Shadal (Shmuel David Luzzatto, 1800-1865) is his anti-philosophical and anti-mystical approach to Torah. His unusual stance yields creative and thought-provoking interpretations that eschew both party lines. I’d like to showcase an example from the beginning of Ki Sisa.

Parashas Ki Sisa (Shemos 30:12) opens with a cryptic warning:

When you take a census of the Children of Israel according to their numbers, every man shall give Hashem an atonement for his soul when counting them, so that there will not be a plague among them when counting them.

The obvious question is: Why would a plague result from taking a census? Rashi (ibid.) explains:

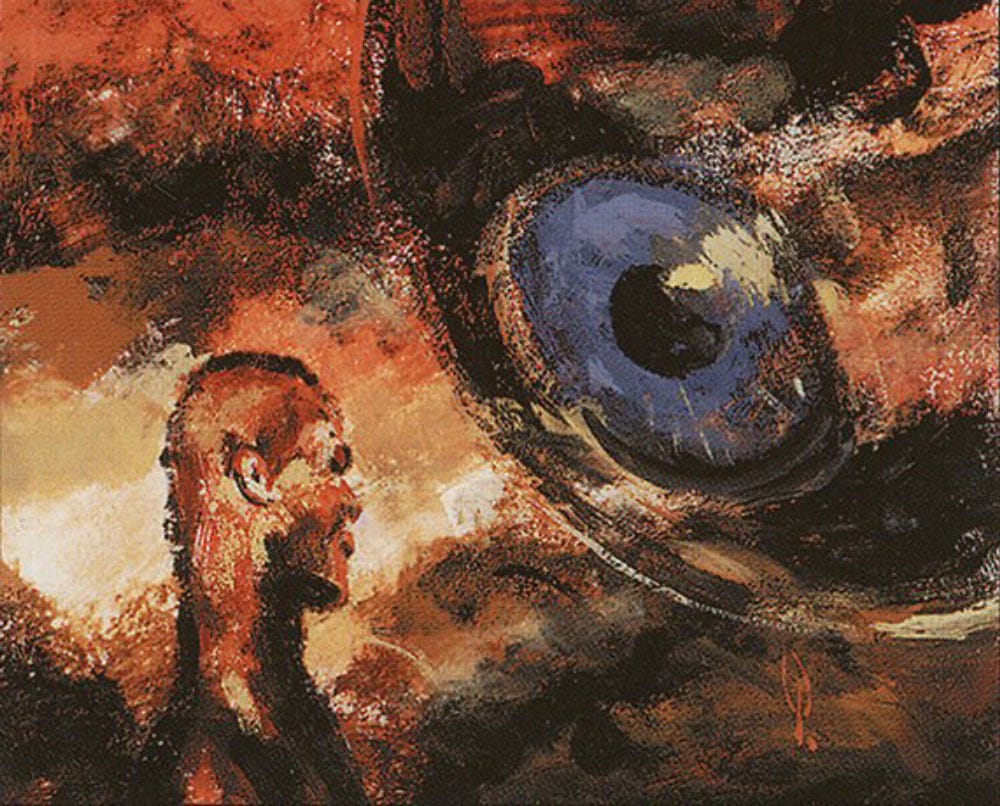

so that there will not be a plague – because counting [causes] ayin ha'ra (the evil eye) to influence [those who are counted], and plague comes upon them, as we find in the days of David.

Rashi refers to an event recounted in II Shmuel 24:

The anger of Hashem again flared against Israel, and He enticed David because of them, to say, “Go count the people of Israel and Judah” … David’s heart smote him after having counted the people, and David said to Hashem, “I have sinned greatly in what I have done. Now, Hashem, please remove the sin of Your servant, for I have acted very foolishly” … So Hashem sent a pestilence in Israel, from the morning until the set time; there died from the people, from Dan to Be’er-Sheva, seventy thousand men.

While we cannot deny the event described in Shmuel, we can certainly question Rashi’s explanation. What exactly is this ayin ha’ra to which he refers, and how does counting people make them susceptible to ayin ha’ra?

Many Jews would not be troubled by this question. They believe ayin ha’ra to be a supernatural force that operates in a manner both mysterious (hence, “supernatural”) and somewhat predictable (e.g., we know that counting people makes them susceptible to ayin ha’ra, even if we can’t understand why). This popular view is reflected in an article on myjewishlearning.com titled Evil Eye in Judaism, which begins:

The “evil eye,” ayin ha’ra in Hebrew, is the idea that a person or supernatural being can bewitch or harm an individual merely by looking at them. The belief is not only a Jewish folk superstition but also is addressed in some rabbinic texts.

The article cites Talmudic statements attesting to the existence of ayin ha’ra and concludes:

Over the centuries, Jews have employed numerous superstitious practices believed to ward off the Evil Eye, such as spitting three times after a vulnerable person’s name is uttered, or saying, when discussing some future plan, “let it be without the evil eye” (“kinehora ” in Yiddish). Jews have also sought to ward off the evil eye with amulets, particularly hamsas.

The article assumes that the ayin ha’ra described in these Talmudic sources is identical to the ayin ha’ra of popular belief. At no point does it question whether ayin ha’ra actually exists or attempt to define what it is and how it works. Let us call this the naïve superstitious view.

At the opposite end of the spectrum are those we might call “rationalists.” Unlike modern-day rationalists, who are likely to reject the notion of ayin ha’ra altogether, the medieval rationalists took its existence for granted and attempted to offer naturalistic explanations. For example, Ralbag (Shemos 30:12 beur ha’milos) writes:

We find that the counting of people causes a plague, as mentioned regarding David when he commanded Yoav, the commander of the army, to count Israel. However, we do not fully understand the exact reason for this.

It seems that this matter relates to the concept of the ayin ha’ra. The damage it causes, as I understand it, results from certain vapors emitted from the eye, composed of excess substances expelled by nature … These vapors can be deadly to certain individuals because they are poisonous to them and because of their susceptibility to such influences. This, I believe, is the cause of the plague that arises from counting: some of those who are counted will die, while others will not, due to differences in their natural susceptibility to this effect.

It is clear that the eye is the organ most vulnerable to this harmful gaze, and through it, the damage reaches the brain, which is close in proximity. For this reason, you will find that there was no concern if the counted objects were part of a person—such as their fingers. These body parts are not naturally affected by this harmful influence … The danger exists only when the gaze is directed at the face, as certain openings allow these vapors to reach the brain. This includes the eyes, due to their sensitivity, as well as the nose and ears, as they are open to the brain.

To our eyes, such explanations seem as laughable as the superstitious views. But we must remember that these proto-scientific speculations represented the best efforts to make sense of what was believed to be a real and otherwise inexplicable phenomenon.

Having examined both the supernatural and naturalistic approaches, we are now in a position to appreciate Shadal’s perspective. He doesn’t even bother addressing the naïve view, but he does single out two “rationalist” camps: the medieval rationalists, who believed in ayin ha’ra and sought to explain it naturalistically, and the modern rationalists of his day, who denied and mocked it. He rejects both before proposing his own explanation.

Here is Shadal’s commentary on Shemos 30:12, translated by Dan Klein, with my own paragraph breaks and emphases. I’ve arranged these excerpts out of order to better highlight the uniqueness of his thinking.

Now I will come to the heart of the matter, that is, the "evil eye." I will note that some of the philosophizers (mitpalsefim), such as Gersonides, sought to explain it in a naturalistic way, expressing the view that the vapors that exude from the eyes of an observer toward the face of one who is seen can be toxic and may injure or kill that person, all according to the nature of the one receiving [such vapors].

Most of the scholars of our era, in contrast, mock the belief in the evil eye, just as they do many other things that cannot be understood in a naturalistic manner.

In my view, both of these groups are mistaken. The world does not behave according to the laws of physical nature alone; rather, there are other laws that were framed by the Supreme Intelligence at the beginning of creation, according to which all events are caused, bringing upon nations and individuals alike both good and evil occurrences that attest to Providence. The [modern] philosophizer looks upon them and says that they are happenstance, while the common folk look upon them and say that they are miraculous. In fact, they are natural events that result inevitably from natural causes, but the events and their causes have all been arranged from the beginning of creation through the wisdom of the Supreme Regulator, blessed be His name.

If we stopped here, Shadal’s intent would not be immediately clear. How can he object to naturalistic explanations, yet turn around and place ayin ha’ra in the category of “natural events that result inevitably from natural causes”?

Shadal continues, clarifying his position by drawing support from a diverse range of sources:

It is this [wisdom] that decreed that the cold weather would be [unusually] harsh and early in the year 5573 (1812), in order to defeat a proud monarch and pacify the entire world. [Klein’s footnote: A reference to Napoleon’s disastrous retreat from Russia, October to December 1812.] It is this [same wisdom] that framed the decree that in the course of public and private events, “pride goeth before the fall” [Prov. 16:18, “Pride goeth before destruction, and a haughty spirit before a fall”].

From this it results that when a person (or likewise an entire nation) stands at the pinnacle of success and exults with pride, producing jealousy in the hearts of his observers, it will befall him that the wheel will turn and an unexpected disaster will come upon him. The common folk will attribute this to the evil eye, or sometimes to the curse of an enemy; but in truth, it is not the eye that does harm or curses that cause evil. Rather, justice is the Lord's, and it is He Who decreed the chain of causation of good and evil, and that "a man's pride shall bring him low, but he that is of a lowly spirit shall attain to honor" (Prov. 29:23). As a French poet said: Du triomphe à la chute il n'est souvent qu'un pas ("From triumph to fall there is often but one step") (Voltaire, La Mort de César).

Shadal’s meaning becomes even clearer when we read his introductory comments on the parashah:

When a person counts his silver and gold, or when a king counts his troops, it is quite likely that he will trust in his wealth or in the multitude of his soldiers, and he will become proud and say, “My force and the vigor of my hand have procured or will procure me prosperity” (cf. Deut. 8:17). But then it will usually happen that the wheel of fortune will turn upon him and an unexpected disaster will befall him (for this is indeed one of the laws of Providence, that “pride goeth before the fall,” and this has proven and continues to prove itself true in all generations with respect to individuals as well as nations and kings).

According to Shadal, what people think of as ayin ha’ra is nothing more than Mishlei in action. I call the phenomenon he describes “Mishleic midah kneged midah (measure for measure)” or “Mishleic karma” (see my article on Mishlei 17:13 for more on this topic). Hashem designed the world so that those who seek to benefit through foolish or wicked means will ultimately suffer the very outcome they hoped to avoid. This is not a mystical or supernatural belief—it is simply minhago shel olam (the way of the world) and an expression of Divine justice.

Why, then, is this portrayed as ayin ha’ra? This is where Shadal’s inner Maimonidean shines:

From this [aforementioned phenomenon] resulted, among all the peoples, a belief in the “evil eye.” Apparently this belief had already become widespread among Israel in the generations before the giving of the Torah. Now God did not wish to abolish this belief altogether, since it is based upon a belief in Providence and keeps a person far from trusting in his own might or wealth, and this is the main principle of the entire Torah. So then what did He do? He commanded that they be enumerated, just when they began to be a unified people, and that they give a ransom of half a shekel per head, and that this money be given over to the service of the tent of congregation as a remembrance before the Lord to ransom themselves. Thus from that day forward they could be counted without fearing the evil eye, for the Tabernacle that was made with the silver of ransom would effect expiation for them.

In other words, just as the Torah tolerated and elevated korbanos, just as it catered to the anthropomorphic conceptions of the ancient Israelites, and just as it reappropriated ancient myths about humanity's origins for its own purposes, so too, the Torah took the popular belief in ayin ha’ra and harnessed it as a vehicle to instill a more sophisticated idea of Divine providence. The Torah endorsed a mystical belief in order to gradually dissolve it.

I characterize this approach as “anti-rationalist rational” because it is reasonable, not driven by rationalist ideology, and does not rely on unsubstantiated mystical beliefs. Shadal walks the middle path.

Let me know what you think!

Like what you read? Give this article a “like” and share it with someone who might appreciate it!

Want access to my paid content without actually paying? If you successfully refer enough friends, you can get access to the paid tier for free!

Interested in reading more? Become a free subscriber, or upgrade to a paid subscription for the upcoming exclusive content!

If you've gained from what you've learned here, please consider contributing to my Patreon at www.patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss. Alternatively, if you would like to make a direct contribution to the "Rabbi Schneeweiss Torah Content Fund," my Venmo is @Matt-Schneeweiss, and my Zelle and PayPal are mattschneeweiss at gmail. Even a small contribution goes a long way to covering the costs of my podcasts, and will provide me with the financial freedom to produce even more Torah content for you.

If you would like to sponsor a day's or a week's worth of content, or if you are interested in enlisting my services as a teacher or tutor. Thank you to my listeners for listening, thank you to my readers for reading, and thank you to my supporters for supporting my efforts to make Torah ideas available and accessible to everyone.

-----

Substack: rabbischneeweiss.substack.com/

Patreon: patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss

YouTube: youtube.com/rabbischneeweiss

Instagram: instagram.com/rabbischneeweiss/

"The Stoic Jew" Podcast: thestoicjew.buzzsprout.com

"Machshavah Lab" Podcast: machshavahlab.buzzsprout.com

"The Mishlei Podcast": mishlei.buzzsprout.com

"Rambam Bekius" Podcast: rambambekius.buzzsprout.com

"The Tefilah Podcast": tefilah.buzzsprout.com

Old Blog: kolhaseridim.blogspot.com/

WhatsApp Content Hub (where I post all my content and announce my public classes): https://chat.whatsapp.com/GEB1EPIAarsELfHWuI2k0H

Amazon Wishlist: amazon.com/hz/wishlist/ls/Y72CSP86S24W?ref_=wl_sharel

Very interesting essay and analysis. It seems to me that the human eye is commonly called “the gateway to the soul,” an exposure of our true nature. Contrarily, the eye is also the means by which we objectify the world, placing ourselves beyond it as “the see-er” rather than “that which is seen.” The threat of the Evil Eye is connected in these parables with the counting of souls, i.e., with objectification, which is to say, domination. The way in which one looks upon another may be with an evil eye, and if one is vulnerable to that gaze, one becomes a reduced person. It’s essential to Judaism to sustain one’s personhood— one’s responsibility as a moral being. To treat others as less than human, or to allow oneself to be regarded as an instrument of any will other than The Lord’s, is to renege on God’s compact with the Jews. The fear of the evil eye is to fear falling into a state of dread— a Kierkegaardian dread that God will abandon you because you are an inadequate vessel, as you are either prone to being dominated (negatively influenced), or prone to dominating (objectifying others, which generates a terrible price.) This is something I think about!

The beginning of Shadal's explanation sound like the Ralbag's and Abarbanel's explanation of King David's sin in counting the Jewish people-שהיה החטא בשדוד משיח אלקי יעקב ונעים זמירות ישראל שם בשר זרועו בבטחו על רוב עמו, ולא היה ראוי שישים בטחונו ברוב עם הדרת מלך כי אם ביי' לבדו שאין מעצור בידו להושיע ברב או במעט.

. Which assuming that you believe in Divine intervention, is quite rational. So I wonder why he has to throw in the part about the evil eye, and the Torah catering to that belief, since the previous explanation for ולא יהיה נגף בפקוד אותם holds up on its own.