The Rabbi Schneeweiss Substack Update: Three Changes for January 2024

This is my announcement for a major change I intend to make in my substack writing, and a chronicle of the epiphany which led to that change. Feel free to skip to the end for the bottom line.

The Torah content for this week has been sponsored anonymously “in honor of Moshe Zucker, friend extraordinaire.”

Click here for a printer-friendly version of this article.

The Rabbi Schneeweiss Substack Update: Three Changes for January 2024

Preface

As indicated by the title, the purpose of this post is to announce some changes on my substack for 2024. These changes came about as a result of an epiphany I had while driving to Virginia for this year’s solo cabin retreat. There is one major change, which I’ll write about at length, and two minor changes, which I’ll mention at the very end.

Primarily, I am writing about these changes and their reasons for myself, to help clarify my own thoughts and solidify my intentions. I also felt it would be appropriate to share these reflections with my readers — especially with my paid subscribers, who provide the most support for my writing. And perhaps some of you have been struggling with your own personal goals or creative endeavors and might benefit from hearing how I’ve struggled with mine.

But I realize that life is short and attention spans are getting shorter. If you’re only interested in the bottom line, feel free to skip to the section entitled “The Bottom Line” at the end of this article.

How This Year Has Gone So Far

To appreciate my epiphany and the changes it sparked, I’d like to provide a recap of how these past eight months have gone.

In Spring 2023 I made the decision to transition from full-time teaching to part-time teaching so that I could finally write the book on Mishlei that Rabbi Moskowitz zt”l and I started working on over a decade ago. Summer 2023 saw two unexpected developments: (1) I quickly realized that I’d rather focus on my substack writing than tackle my Mishlei book right away; (2) I accepted a part-time job teaching at a Jewish Academy in New England. This job mostly involves remote instruction over Zoom, but includes a commitment to teach a couple of days each month in person. (I spoke about both changes at length in my podcast episode “Two MAJOR Professional/Life Updates for the 2023-2024 Academic Year.”)

When the school year started in August 2023, I was optimistic about my ability to balance my part-time teaching duties with my writing ambitions. Because every new job requires an adjustment period, I set (what I thought was) a humble writing goal: instead of writing ONE article each week, I’d write TWO. Specifically, I’d continue writing my Friday article on the parashah, as I had succeeded in doing throughout the 2022-2023 school year, and I’d write an additional article on a topic of my choice, as I had done during the summer of 2023. To keep my writing from getting overly ambitious, I would continue to default to the 1-to-2-page format I had been using for the past few years (which I wrote about in “The 1-Page Article: a Summer 2021 Experiment”). I had a high degree of confidence in this plan because it involved the same two types of articles I had been writing for over a decade, and I was familiar with the amount of work required for each.

Midway through Fall 2023, it dawned on me that my return to the classroom was a mixed blessing. I love my new students, and it has been rewarding to work with teenagers again after “leveling up” as an educator during my three years of post-COVID post-high-school teaching. However, I didn’t count on this part-time job being so time-consuming. Frankly, (to use some Mishlei slang) I had forgotten how much ox-filth is involved in teaching at a traditional Jewish day school. By “ox-filth” I am referring to all the tasks, responsibilities, and clerical drudgeries beyond teaching and lesson planning (which I still love as much as I always have). I had also forgotten how devoted I tend to be to my high school students, and how much of myself I invest in each one of them. Lastly, I had miscalculated how draining and disruptive my monthly in-person teaching sessions would be to my schedule and to the rhythm of the year (as I chronicled in my recent article “God of Time or Dog Eating Its Own Vomit?”).

In December 2023, I finally came to terms with the bitter truth: my year was not going as I had hoped. Not only had I repeatedly failed to meet my target of writing two articles per week, but I often struggled to complete my Friday parashah article in time for Shabbos. There were a handful of good weeks on which my article would be written, recorded, and ready-to-publish by Friday morning. On most other weeks, I wouldn’t even start writing the article until Thursday. On a handful of occasions, I’d crank out the whole article from start to finish in a stressful, adrenaline-fueled marathon of writing in the few hours between the conclusion of my Friday morning teaching sessions and the onset of Shabbos.

The worst part was facing the fact that there were so many articles I set out to write at the beginning of the summer (some of which I teased in my Summer 2023 Update), but I had barely written any of them. Every week brought new ideas for articles I wanted to write, but most of them still haven’t seen the light of day.

As my end-of-the-semester burnout flared and my winter break commenced on December 22, I found myself at a crossroads, facing questions about the remainder of the school year in 2024. Should I resign myself to the fact that this is just what the next six months are going to be like, or is there some way I can turn things around? Does the solution lie in figuring out how to carve out more time in my day, or will I have to make some compromises to achieve my goals? Can I change my habits to optimize my weekly routine, or will attempting to do so be detrimental to my mental health?

These were the questions on my mind as I set out on the six hour drive to Virginia for my annual solo cabin retreat.

The Epiphany

Have you ever struggled with a problem in your life, only to realize it was caused by a self-imposed rule which once served as a boon but had since outlived its original purpose? That was the form my epiphany took. I realized that nearly all my troubles stemmed from my slavish adherence to the unwritten self-imposed commandment: “thou shalt not write an article on a non-parashah topic until thou hast written an article on the parashah.”

I totally get how this coalesced into a rule in my mind. The convenience of the dvar Torah genre is what allowed me to achieve last year’s goal of writing one article each week. The narrow scope and familiar format allowed me to bypass the decision paralysis of choosing what to write about each week and how to go about writing it. Once I launched my substack, and became aware that people were printing out my Friday article for Shabbos each week, I felt obliged to supply them with what (I believed) they had come to expect from me. The more paid subscribers joined, the more I felt like this was a binding contract. What began as a way to relieve myself of writing-related pressures ended up creating writing-related pressures, and the change was so gradual that it didn’t even register until now.

This rule, combined with my busy schedule, resulted in me writing only a single article on the parashah most weeks. Again and again I fell into the same pattern. I would begin my week knowing what I wanted to write about on the parashah and having an exciting plan for a non-parashah article. I told myself, “People are expecting you to write an article on the parashah, so you should really take care of that first.” I’d delude myself into thinking I could polish that off by Monday or Tuesday and write the second article on Wednesday or Thursday. Before I knew it, my teaching responsibilities would accumulate and I’d find myself midway through the week, not having even begun writing my parashah article.

This resulted in an additional emotional obstacle I hadn’t noticed. Because my weekly parashah article had become a hurdle I had to jump over to be able to write what I really wanted to write, and because I crashed into that hurdle week after week, I began relating to my dvar Torah as a burden. Sure, I’d get excited once I found a topic and got into the flow-state of writing, but until that point, my psyche related to the dvar Torah as another task I was obligated to do, and that made me resent it. (This came to a head on 3/24/23, when I wrote “Musings on the Fact that There is No Article This Week.”)

And there was one more factor that fomented my discontent about my writing and contributed to my epiphany. On December 21, the day before I left for my cabin, I read an article by my friend Rabbi Akiva Weisinger entitled “The Devar Torah as a Written Form.” It was his opening paragraph that stuck with me:

So a while back I read an article about things you shouldn’t do in a devar torah. To my consternation, a lot of the things listed in the article were things I had done, many of them as a matter of habit. Some things I scrapped as a result of that article. Some things I didn’t, and continue doing out of defiance. Like starting a devar torah off with the word “so”.

I realized, with horror, that because 90% of my articles were divrei Torah, my writing style and voice had begun to stagnate. Instead of saying whatever I wanted to say however I wanted to say it, I had fallen into the drab writing conventions of this worn-out, humdrum, yawn-inducing genre. I have a feeling that this bothers me more than it bothers my readers — because, evidently, people still read what I write each week (though I can’t tell how often they yawn when reading) — but that’s no excuse for subpar writing, and it’s certainly no excuse for stifling my voice.

These realizations led to my epiphany, a solution which is as simple as it is inevitable: I must free myself from the tyranny of the weekly dvar Torah. It’s not that I need to stop writing about the parashah. It’s that I need to stop prioritizing the weekly dvar Torah over all my other writing. Instead of writing a dvar Torah before writing what I want, I’ll do the reverse: focus on writing what I want, and then write a dvar Torah — only if I have time, and only if am so inclined.

This will solve my problems without necessitating any changes in my schedule:

I will no longer relate to the weekly dvar Torah as a burdensome task I need to check off before getting to the writing I’m passionate about.

I will get to write what I want to write, including more paid subscription articles (which is where the really juicy stuff will be).

I’ll get to start off the week with pleasurable writing.

This might even result in a quicker turnaround time, allowing me to write my preferred article in the first half of the week and then write a dvar Torah later — though if it doesn’t, that’s totally fine.

This will give me ample opportunity to find my writerly voice again and (God willing) help me to develop into a more mature writer.

What about the hordes of readers who stand waiting with their pitchforks and who will burn me at the stake if I don’t provide them with the parashah article I owe them? Allow me to reply with a radical answer: maybe those readers don’t exist. Maybe the people who follow my Torah content will be interested in whatever I decide to write about, even if it’s not on the parashah. Maybe, by writing what I’m passionate about, there will be even more interest in what I have to say.

And what if there are readers who have been relying on my divrei Torah as an integral part of their Shabbos reading? Somehow, I think they’ll be okay. There are plenty of other good divrei Torah out there by writers greater than I am. And if they really want something from me, I’m sure they can find something in the archives.

How My Cabin Reading Crystallized My Resolve

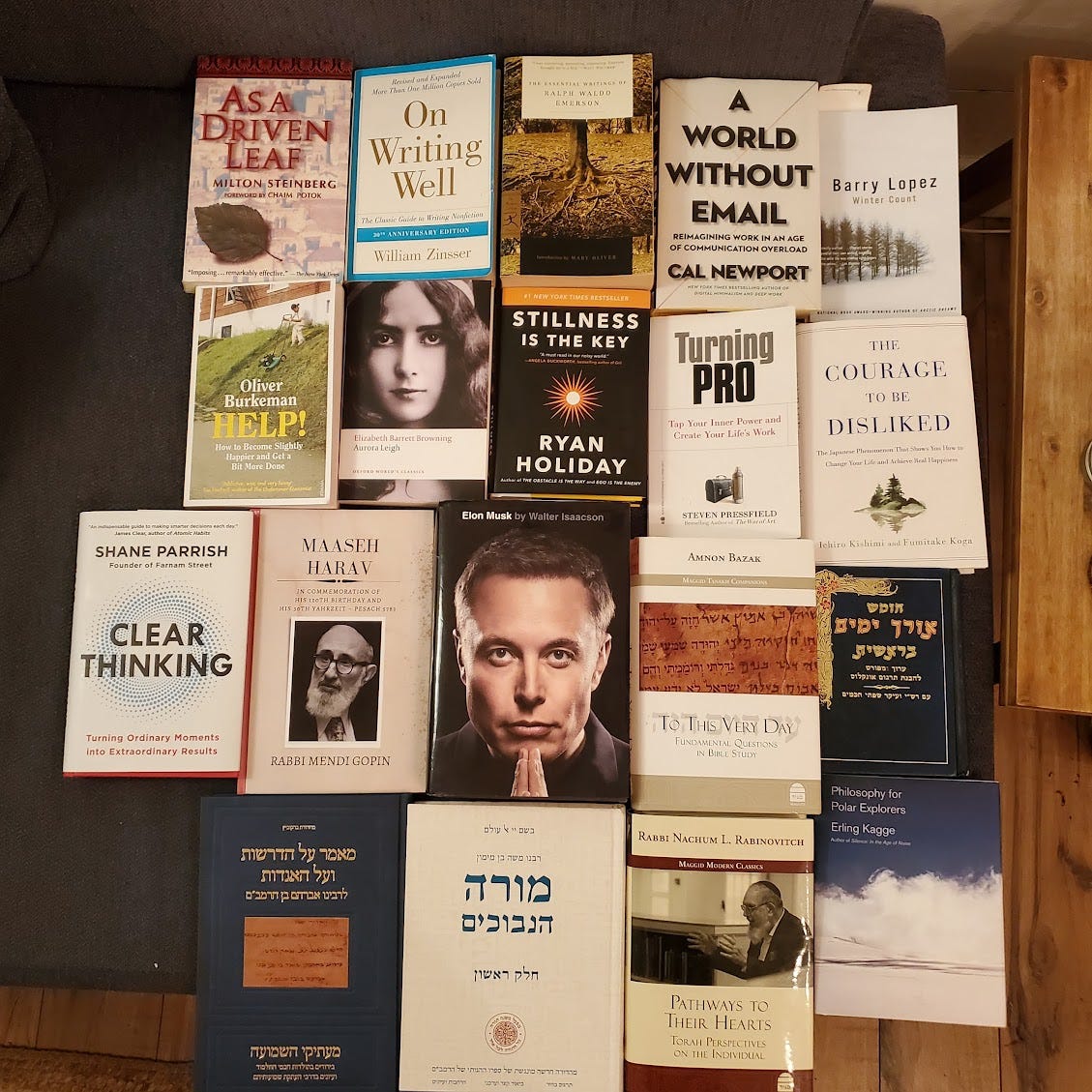

There are two activities I do during my annual cabin retreats: read books and tend the fire. I usually bring a couple dozen books with me and then read whatever catches my fancy. This year, without any conscious planning on my part, my reading coalesced around a handful of themes and messages which helped me develop my epiphany.

The most influential catalyst for my upcoming changes was Elon Musk (2023), Walter Isaacson’s latest biography. For all his faults, Musk exhibits two qualities I admire: (1) when he wants to make something happen, he’ll do whatever it takes to make it happen, and (2) he is ruthless in his demand for efficiency. The book was replete with examples in which Musk asked his employees (and himself) questions like: “Why are we doing it this way?” “What purpose does that step serve?” “Can it function without this component?” “Who made that rule and who says we have to follow it?” Although he never quite says it in so many words, Musk embodies one of my favorite Bruce Lee quotations:

“It is not daily increase but daily decrease. Hack away the unessential! The closer to the source, the less wastage there is.”

I was inspired by Elon’s combination of personal striving and rigorous streamlining of his processes. If I hired him as a manager to oversee my substack, there is no way he’d let me sit there with my hands tied by my own self-imposed writing restriction which didn’t serve my alleged goals. Instead, he’d yell and me, saying: “My life’s goal is to get to Mars, and every day I make sure I’m doing whatever it takes to get there. You claim you want to write articles about topics that interest you, so why are you forcing yourself to write divrei Torah instead? Delete that rule and do what you’re meant to do!”

Another book I read was The Courage to Be Disliked (2018), by Ichiro Kishimi and Fumitake Koga — a book which, ironically, I disliked. Although the subtitle reads: “The Japanese Phenomenon That Shows You How to Change Your Life and Achieve Real Happiness,” the book is not at ALL about anything Japanese. Instead, it’s an overview of Alfred Adler’s psychology repackaged as a self-help guide written in the form of a dialogue between a Youth and a Philosopher. My main takeaway from this book is illustrated in the following excerpt, in which the Youth tells the Philosopher about a friend of his:

I have a friend, a guy, who has shut himself in his room for several years. He wishes he could go out and even thinks he’d like to have a job, if possible. So he wants to change the way he is. I say this as his friend, but I assure you he is a very serious person who could be of great use to society. Except that he’s afraid to leave his room. If he takes even a single step outside, he suffers palpitations, and his arms and legs shake. It’s a kind of neurosis or panic, I suppose. He wants to change, but he can’t.

The Philosopher asks the Youth what he thinks is the reason why his friend can’t go out. The Youth suggests some psychodynamic explanations:

It could be because of his relationship with his parents, or because he was bullied at school or work. He might have experienced a kind of trauma from something like that. But then, it could be the opposite — maybe he was too pampered as a child and can’t face reality.

That’s when the Philosopher introduces the Youth to the foundation of Adlerian psychology:

… in Adlerian psychology, we do not think about past “causes” but rather about present “goals” … Your friend is insecure, so he can’t go out. Think about it the other way around … Your friend has the goal of not going out beforehand, and he’s been manufacturing a state of anxiety and fear as a means to achieve that goal … This is the difference between etiology (the study of causation) and teleology (the study of the purpose of a given phenomenon, rather than its cause). Everything you have been telling me is based in etiology. As long as we stay in etiology, we will not take a single step forward.

The book goes on to discuss the implications of this distinction. I don’t yet know what I think about Adler’s approach as a framework, but it definitely rings true to me in particular cases, including my present dilemma.

It reminds me of the memorable scene in a bad romantic comedy called The Answer Man (2009). Jeff Daniels plays an author named Arlen Faber who wrote a best-selling spiritual book which earned him a reputation for having all the answers to life’s big questions. Arlen is a jerk who is ultimately drawn out of his reclusive lifestyle by a romance with Elizabeth, his chiropractor, and a friendship with Kris, a young recovering alcoholic. Kris strikes a deal in which he gets to ask Arlen one question each day. Here’s the memorable snippet of dialogue:

Kris: Why can't I do the things I want to do? There's so much I know I'm capable of and I never actually do. Why is that?

Arlen sips his coffee and says in a nonchalant, “no big deal” sort of way:

Arlen: The trick is to realize that you're always doing what you want to do. Always. Nobody is making you do anything. Once you get that, you see that you're free and that life is just a series of choices. Nothing happens to you. You choose.

Nobody is making me write parashah articles. Nobody but me. If that’s what I’ve been doing, then that’s because some part of me wants to do it for some purpose. Whether that purpose is wanting to please others, or wanting to blame the (real or imagined) expectations of others for my own writing difficulties, or turning-away-in-fear that I don’t have what it takes to write what I claim I want to write, or something else — perhaps there is some purpose I’ve been trying to achieve which has inclined me to choose to remain in this stuck mode of writing.

One answer was suggested by another book I read at the cabin, Turning Pro: Tap Your Inner Power and Create Your Life’s Work (2012), by Steven Pressfield, about the difference between “amateurs” and “pros.” My one-word review of this book is “meh,” but it had its share of insights. One of the messages that spoke directly to me (with its Dale Carnegiean hokey language) was this series of “hard-hitting” truths:

Though the amateur’s identity is seated in his own ego, that ego is so weak that it cannot define itself based on its own self-evaluation. The amateur allows his worth and identity to be defined by others.

The amateur craves third-party validation.

The amateur is tyrannized by his imagined conception of what is expected of him …

Paradoxically, the amateur’s self-inflation prevents him from acting. He takes himself and the consequences of his actions so seriously that he paralyzes himself.

The amateur fears, above all else, becoming (and being seen and judged as) himself.

Becoming himself means being different from others and thus, possibly, violating the expectations of the tribe, without whose acceptance and approval, he believes, he cannot survive.

By these means, the amateur remains inauthentic. He remains someone other than who he really is.

And the list of cabin-reading-driven “Aha!” moments goes on. The essays Intellect (1841) and Plato; or, the Philosopher (1850), by Ralph Waldo Emerson, reminded me how a human being can flourish by following their own mind, wherever it takes them. Philosophy for Polar Explorers (2020), by Erling Kagge, reawakened my sense of adventure and risk-taking (albeit not in the form of visiting the earth’s three poles). A World Without Email (2021), by Cal Newport, made me think about how I can restructure my workflow to facilitate better writing. On Writing Well (2006), by William Zinsser, reminded me of the many ways I yearn to improve as a writer.

The Bottom Line

Since the timing of these changes coincides with the new year, I’ll formulate my aspirational changes in the form of anti-resolutions. There are three:

NOT to be bound by the self-imposed tyranny of the weekly parashah: I will still write an article at least every Friday, but I will no longer prioritize a weekly dvar Torah on the parashah. This will allow me to write what I’m excited to write about, to rediscover and develop my voice as a writer, and to restore writing as an activity I love instead of an obligation I must fulfill.

NOT to be bound by the self-imposed tyranny of page-length restrictions: I didn’t write about this in the article above because there’s not much to write about. Basically, I’ve encountered diminishing returns in my efforts to edit the final article down to exactly 1-2 PDF pages, often spending FAR too long devising ways to shave off a word here or a sentence there. I still plan to aim for that length, but if the article I’m writing ends up being longer than that — or needs to be longer than that — then so be it.

NOT to choose what to write about based on what I imagine other people want or expect. I have struggled with this for years, and I’ll continue to struggle with it for years to come. I wrote about it in 2015 and 2010 in my evergreen article “Playing with Torah” and in the recent sequel “Octopuses, MDMA, and the Ecstasy of Torah.” Basically, I need to stop worrying what other people think, and get back to living the life I want to live.

Here’s hoping (and davening) for a year of writing that is as fulfilling for me as it is enlightening for you! Thank you, as always, for your interest and your support. I look forward to hearing any feedback on this or anything else that I write … even though I’m going to listen to myself and try to do what is best for me!

If you have anything you want to tell me about my substack (or my Torah content in general) in 2024, now’s the time. Lay it on me!

Like what you read? Give this article a “like” and share it with someone who might appreciate it!

Want access to my paid content without actually paying? If you successfully refer enough friends, you can get access to the paid tier for free!

Interested in reading more? Become a free subscriber, or upgrade to a paid subscription for the upcoming exclusive content!

If you've gained from what you've learned here, please consider contributing to my Patreon at www.patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss. Alternatively, if you would like to make a direct contribution to the "Rabbi Schneeweiss Torah Content Fund," my Venmo is @Matt-Schneeweiss, and my Zelle and PayPal are mattschneeweiss at gmail. Even a small contribution goes a long way to covering the costs of my podcasts, and will provide me with the financial freedom to produce even more Torah content for you.

If you would like to sponsor a day's or a week's worth of content, or if you are interested in enlisting my services as a teacher or tutor. Thank you to my listeners for listening, thank you to my readers for reading, and thank you to my supporters for supporting my efforts to make Torah ideas available and accessible to everyone.

-----

Substack: rabbischneeweiss.substack.com/

Patreon: patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss

YouTube: youtube.com/rabbischneeweiss

Instagram: instagram.com/rabbischneeweiss/

"The Stoic Jew" Podcast: thestoicjew.buzzsprout.com

"Machshavah Lab" Podcast: machshavahlab.buzzsprout.com

"The Mishlei Podcast": mishlei.buzzsprout.com

"Rambam Bekius" Podcast: rambambekius.buzzsprout.com

"The Tefilah Podcast": tefilah.buzzsprout.com

Old Blog: kolhaseridim.blogspot.com/

WhatsApp Content Hub (where I post all my content and announce my public classes): https://chat.whatsapp.com/GEB1EPIAarsELfHWuI2k0H

Amazon Wishlist: amazon.com/hz/wishlist/ls/Y72CSP86S24W?ref_=wl_sharel

I think this my favorite post of yours since the beginning of the Substack! I look forward to reading to what you are excited to write about. I actually did sense that some of the parsha articles occasionally lacked the unique "voice" of Rabbi Matt Schneeweiss... like the voice from this awesome line: "I realized that nearly all my troubles stemmed from my slavish adherence to the unwritten self-imposed commandment: 'thou shalt not write an article on a non-parashah topic until thou hast written an article on the parashah.'"

Can’t watch right now (I’m out) but will say that I suggested it for editing, not writing ;-)