Yisro: Shadal’s Unfortunate Stance on Idolatry, Belief, and the Value of Knowledge

Perhaps this article will expose me as a fool, an ignoramus, a haughty dilettante—or all three. But I had to write it, if only to be shown how wrong I am. Either way, we're gonna learn some Shadal!

The Torah content for the entire month of February has been sponsored by Y.K. with gratitude to Rabbi Schneeweiss for providing a clear and easily accessible path to personal growth via his reliably interesting and inspiring Torah content.

Click here for a printer-friendly version of this article.

Yisro: Shadal’s Unfortunate Stance on Idolatry, Belief, and the Value of Knowledge

Preface

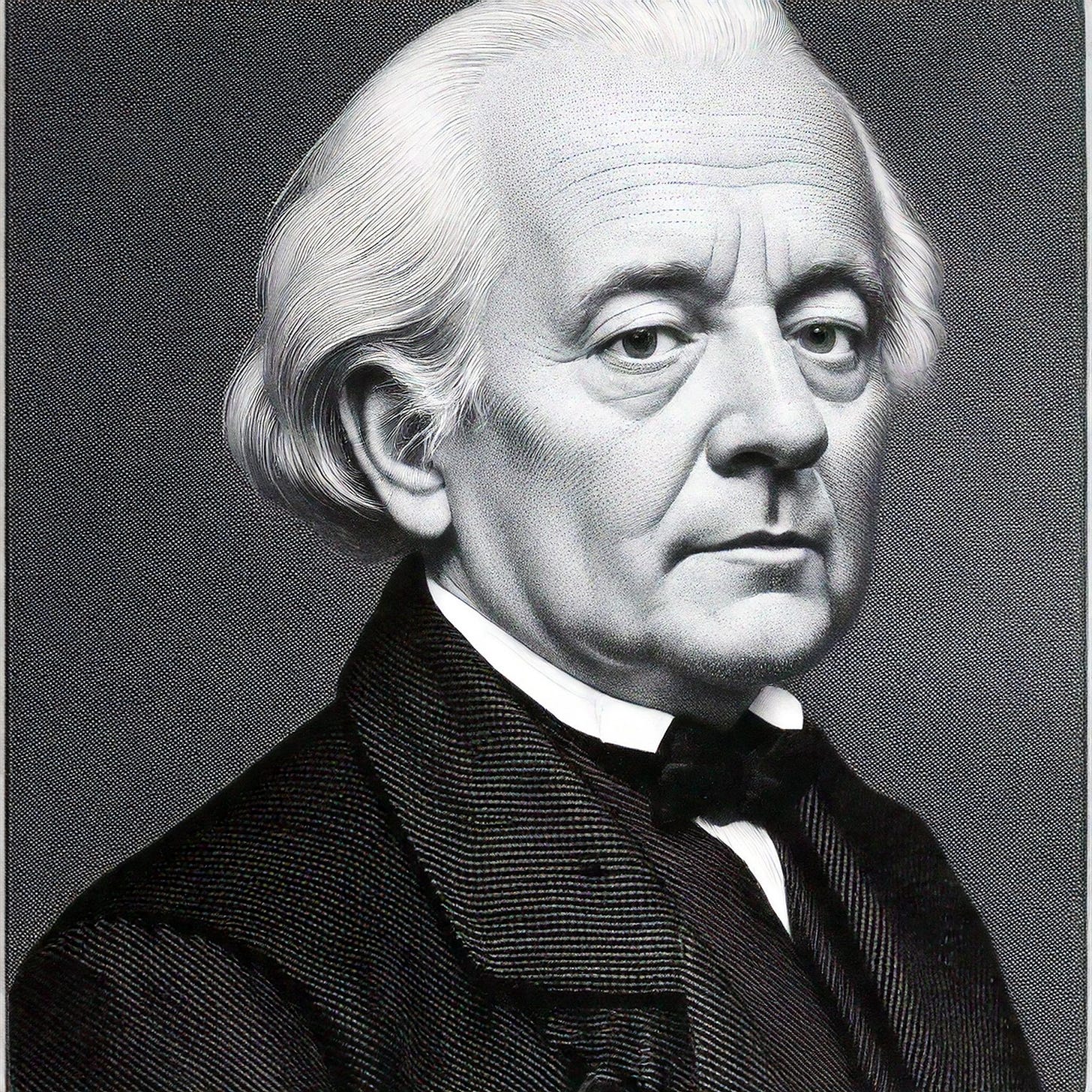

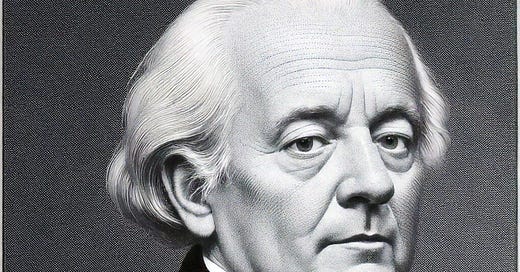

I belong to a small Facebook chavurah (learning group) called “To know Shadal is to love Shadal.” Its members share an interest in the Torah of Shmuel David Luzzatto (1800-1860), whose works I only discovered in the last five or six years. I may not know Shadal as well as some of the other members, but I certainly love him. His modern, eclectic, peshat-centered approach—combined with his anti-philosophical and anti-mystical orientation—consistently yields refreshing insights that have greatly enriched my learning and methodology. His Italian passion and biting wit make him a delight to read.

That being said, I will paraphrase what the Baal ha’Maor wrote about the Rif, who paraphrased what Ibn Janach wrote about Ibn Hayyuj, who paraphrased what Aristotle wrote about Plato: “My love for Shadal is great, but my love for truth is greater still.” I believe Shadal is fundamentally wrong in his understanding of the most significant verse in this week’s parashah.

My goal in this article is not to attempt to refute Shadal’s ideas on their own terms or even to show that they stem from a flawed understanding of Torah. Rather, I aim simply to articulate the difference between his view and mine. While I believe my view is rooted in the hashkafah (worldview) of the Geonim, Rishonim, and Acharonim from whose waters I drink, I have chosen to use the Rambam as a stand-in for all of them on this issue, as he is their most prominent and articulate spokesperson on the matters I will discuss.

Rambam on Lo Yihyeh Lecha

The second commandment in the Decalogue is “Lo yihyeh elohim acherim al panai – You shall have no other gods before Me” (Shemos 20:2). Rambam (Sefer ha’Mitzvos: Lo Taaseh #1) explains:

The first of the mitzvos lo taaseh (negative commandments) is the prohibition against entertaining the thought that anything other than Hashem possesses divinity. The source of this mitzvah is His statement—may He be exalted above any attribution of speech—"You shall not have other gods before Me.”

Rambam codifies Lo Yihyeh Lecha in the opening halachos of the Mishneh Torah. After introducing the concept of God as the Necessary Existence (Hilchos Yesodei ha’Torah 1:1-6), he writes:

Knowledge of this principle is a mitzvas aseh, as it is stated: “Anochi Hashem Elokecha – I am Hashem, your God” (Shemos 20:2). Anyone who entertains the thought that there exists a god other than this has transgressed a lo taaseh, as it is stated: “You shall not have other gods before Me.” And he has denied the ikkar (fundamental principle), for this is the ikkar upon which everything depends.

According to the Rambam, conviction in Hashem’s existence and denial of all other gods form the bedrock of Judaism. In this sense, Anochi and Lo Yihyeh Lecha are the most important mitzvos in the Torah.

Shadal on Lo Yihyeh Lecha

Here is an excerpt from Shadal’s commentary on Lo Yihyeh Lecha as translated by my friend, the scholar Dan Klein:

But why was the Holy One, blessed is He, so insistent as to the belief in His Oneness? Why should He care if we were to worship others besides Him? Does idol worship cause harm to civil society?

Yes, it does. This world in which we live, if examined part by part, will be found to contain much evil, as everyone knows. However, if the world is examined as a whole, every wise person understands that it is only good, for there is nothing in it that is evil per se; rather, anything [apparently] evil in the world is, in its essential nature, for the good. One who believes in One God finds it possible to imagine Him as essentially good and possessing every kind of perfection. This image would lead the believer to conclude that God loves goodness and good people, and that He hates evil and evil people. This, in turn, would lead the believer to better his ways, in order to find favor with his God. On the other hand, one who believes in many gods, that is, one who accepts as divine the forces of nature, each one apart from the other, or some created beings, whichever they may be, will inevitably have one or more gods that are evil by nature, or that have some imperfection or diminution. This will result in his inclination toward evil or imperfection, as he will think that in so doing, he will find favor with such-and-such a god whose ways are so. This is known from experience, as anyone knows who has read the annals of the ancient peoples and their customs.

Besides, only a single God is likely to be conceived as possessing the epitome of perfection. If many gods are imagined to exist, each one of them must necessarily be lacking and imperfect, for the power of one will limit that of the other. As a result, jealousy, hatred, and rivalry will be ascribed to the heavens above, as is known from the beliefs of ancient peoples; and as a further inevitable result, human relations will suffer. Polytheistic beliefs cause the hearts of the various peoples to be sundered, for the members of one nation, who worship a particular god, will despise the members of another nation who worship another god, and they will claim to lack any relationship with them, as if those others were not human beings like themselves.

Only those who believe in One God know that we all have one Father, that One God created us, and that all humankind is dear to Him. Indeed, it was only after the Torah of Moses was spread throughout the world that the peoples began to recognize that we are all brothers. For all of these reasons, God wanted the knowledge of His Unity to be maintained in Israel, and thus He threatened them with all these threats [see below, v. 5] and employed such hyperbolic language, so that they should not worship other gods. All of this was not only for the benefit of Israel in particular, but for the benefit of the whole human race, for out of Israel was the Torah to come forth, and knowledge of God’s Unity was to spread from them gradually to all humankind, so that in the end of days the world was to be filled with the knowledge of God.

Shadal makes a compelling argument about the detrimental effects of polytheism on mankind. I have no disagreement there, and I suspect the Rambam wouldn’t either. My issue is not with Shadal’s answers but with his questions. Specifically, he seems to regard knowledge not as an intrinsic good but as valuable only for its utility. His first two questions—“But why was the Holy One, blessed is He, so insistent as to the belief in His Oneness? Why should He care if we were to worship others besides Him?”—raised an eyebrow, but his third explanatory question, “Does idol worship cause harm to civil society?” tipped his hand.

Yedias Hashem (Knowledge of God) as the Ultimate End

To the Rambam, the answers to Shadal’s first two questions are obvious. Why does God care about belief in His Oneness and disbelief in other gods? Because such knowledge is “the foundation of foundations and the pillar of all wisdom” (Hilchos Yesodei ha’Torah 1:1). God created man “in His form” (Bereishis 1:27). According to the Rambam—and, last I checked, all the major commentators among the Rishonim and early Acharonim—this means that humans have the ability to seek truth and comprehend knowledge, transcending physicality and sense-perception to engage with the world of ideas. To the extent we can speak of human purpose, this is it: “comprehending and knowing Me” (Yirmiyahu 9:23).

Although, as Rambam points out (Moreh 3:54), the verse continues, “that I am Hashem, Who does chesed (kindness), mishpat (justice), and tzedakah (righteousness) on earth, for in these is My desire,” this does not mean that knowledge of Hashem is merely a means to chesed, mishpat, and tzedakah. Rather, as Rambam explains:

It follows that the purpose mentioned in this verse is to clarify that the true perfection of a person … is attaining knowledge of Hashem (may He be exalted) to the extent of his ability, and understanding His providence over His creations in their existence and governance, how it operates. The conduct of such a person will always be directed by that knowledge, consistently aiming for chesed, tzedakah, and mishpat, in order to emulate Hashem in his actions, in the manner we have explained several times in this treatise.

In other words, chesed, mishpat, and tzedakah are not the purpose of yedias Hashem but rather its natural outcome and full expression. The Rambam would acknowledge that belief in God’s Oneness has socially beneficial effects, but he would say that God cares about these beliefs because they are the most fundamental truths that can be known—and that knowledge is valuable as an end in and of itself.

Shadal, apparently, is not satisfied with that answer. That is why he asks his third question: “Does idol worship cause harm to civil society?”—and is only satisfied by the answer, “Yes, it does.” If the answer were, “No,” Shadal would be left in a state of perplexity.

Rambam does not deny that the Torah teaches certain beliefs for their utilitarian ends, but he would take issue with Shadal’s implication that this is the only reason for such beliefs. In the Moreh ha’Nevuchim (3:28), Rambam divides all beliefs [1] promoted by the Torah into two categories: “true” and “necessary”:

The correct beliefs through which ultimate perfection is attained are presented by the Torah only in terms of their final objectives. The Torah has called upon us to hold by them in a general manner—namely, [to believe in] the existence of Hashem (may He be exalted), His Oneness, His knowledge, His power, His will, and His eternality. These are all ultimate ends, which can only be elucidated in detail and defined precisely after one has acquired knowledge of many [other] views. Similarly, the Torah has called upon us to hold certain beliefs, the acceptance of which is necessary for the proper functioning of the political order. Such, for instance, is our view that He (may He be exalted) expresses wrath toward those who rebel against Him, and that it is therefore necessary to fear, dread, and guard oneself against disobedience…

Understand what we have said regarding beliefs: the purpose of a given mitzvah may be solely to instill a correct belief, nothing more—as, for instance, conviction in His Oneness, Eternality, and incorporeality. In other cases, a particular belief is necessary for the removal of injustice or for the acquisition of a noble moral trait—for instance, the view that He (may He be exalted) expresses wrath toward those who commit injustice, as it is stated: “My anger shall blaze…” (Shemos 22:23); and the view that He (may He be exalted) immediately answers the cry of the oppressed or afflicted: “And it shall be that when he cries out to Me, I will listen, for I am gracious” (ibid. 22:26).

In other words, the Torah teaches “true beliefs” (such as God’s Oneness) because they reflect objective reality, and knowledge of reality is what makes us human. The Torah also teaches “necessary beliefs” (such as the belief in swift Divine retribution) because of their social utility. Shadal, on the other hand, reduces belief in God’s Oneness and exclusivity to a merely utilitarian function—necessary for political welfare.

The Purpose of Learning

I anticipate that some might read what I’ve written so far and object, arguing that Judaism does not purport to teach “true beliefs” or that the very notion of “true beliefs” is epistemologically unsound. Such objections have become increasingly fashionable in recent decades, due to the rise of so-called “Orthoprax Judaism” and postmodernism. But it’s clear to me that Rambam would not hold by such views—or, if one could entertain the thought that he would accept them, he would no longer be the Rambam we study. I bring this up not because I accept this objection—I don’t, and neither would the Rambam—but to show that even if the Torah did not teach “dogmas,” I would still take issue with Shadal’s stance on why we learn and on what it means to be human.

As I wrote above, to be human is to be a truth-seeker. The highest level a person can reach is to be an oved me’ahavah (one who serves God out of love) who learns lishmah (for its own sake). Rambam first expresses this in his introduction to Perek Chelek, writing: “Ein tachlis ha’emes ela l’daas she’hu emes”—the only purpose of truth is to know that it is true. He echoes this in the Mishneh Torah (Hilchos Teshuvah 10:2), writing:

One who serves [Hashem] out of love is involved in Torah and mitzvos and walks on the paths of wisdom not because of any worldly matter—neither out of fear of harm nor in order to inherit the good; rather, oseh ha’emes mipnei she’hu emes (he does what is true because it is true), and the good will ultimately come about on its own. [2]

According to Shadal, the purpose of the two fundamental truths on which the entire Torah rests is not to know that they are true, but to promote social harmony. What, then, does he hold is the value of learning Torah lishmah? Where is there room for such a concept in his hashkafah?

Concluding Thoughts: An Ongoing Conversation

I recognize that Shadal’s fundamental opposition to the Rambam’s worldview runs far deeper than this single issue. His attitude toward the Rambam is encapsulated in a parenthetical remark from his commentary on Anochi (Shemos 20:2), regarding the Rambam’s view on the nature of the Revelation at Sinai:

I will make no conclusion as to what Maimonides’ rationale was in this exalted matter, for it is exceedingly difficult to penetrate its mystery … Blessed be the Omnipresent, Who has freed us from that philosophy that prevailed in Maimonides’ days, toward which he tended more than he should have, even if his intention was for the good.

Unlike many who vilified the Rambam throughout history, Shadal appreciated his achievements—yet he still regarded his own outlook as more “evolved” than “Maimonideanism.”

I’ll conclude this article by reiterating the point I began with: I love Shadal, but I am aware that my knowledge of his thought is woefully incomplete. I have no doubt that he addresses the issues I’ve raised here elsewhere in his writings. I would love to see other sources where he discusses the value of knowledge, the nature of Jewish belief, and what it means to learn Torah lishmah. My hope is that by articulating my disagreement with Shadal based on my limited understanding of his views, those more familiar with his work will share what they know and help me better understand what he holds and why he holds it.

[1] I generally translate the Judeo-Arabic term אעתקאד as “conviction” rather than “belief,” based on Rambam’s definition in Moreh 1:50. However, in the context of presenting the difference between Shadal and Rambam, “belief” is a better fit.

[2] I generally translate the phrase וסוף הטובה לבוא בכלל as … oh, who am I kidding? I’ve never known how to translate that.

Whether you agree or disagree with my analysis and assessment, or think I’m an ignorant fool, I’d love to hear your thoughts!

Like what you read? Give this article a “like” and share it with someone who might appreciate it!

Want access to my paid content without actually paying? If you successfully refer enough friends, you can get access to the paid tier for free!

Interested in reading more? Become a free subscriber, or upgrade to a paid subscription for the upcoming exclusive content!

If you've gained from what you've learned here, please consider contributing to my Patreon at www.patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss. Alternatively, if you would like to make a direct contribution to the "Rabbi Schneeweiss Torah Content Fund," my Venmo is @Matt-Schneeweiss, and my Zelle and PayPal are mattschneeweiss at gmail. Even a small contribution goes a long way to covering the costs of my podcasts, and will provide me with the financial freedom to produce even more Torah content for you.

If you would like to sponsor a day's or a week's worth of content, or if you are interested in enlisting my services as a teacher or tutor. Thank you to my listeners for listening, thank you to my readers for reading, and thank you to my supporters for supporting my efforts to make Torah ideas available and accessible to everyone.

-----

Substack: rabbischneeweiss.substack.com/

Patreon: patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss

YouTube: youtube.com/rabbischneeweiss

Instagram: instagram.com/rabbischneeweiss/

"The Stoic Jew" Podcast: thestoicjew.buzzsprout.com

"Machshavah Lab" Podcast: machshavahlab.buzzsprout.com

"The Mishlei Podcast": mishlei.buzzsprout.com

"Rambam Bekius" Podcast: rambambekius.buzzsprout.com

"The Tefilah Podcast": tefilah.buzzsprout.com

Old Blog: kolhaseridim.blogspot.com/

WhatsApp Content Hub (where I post all my content and announce my public classes): https://chat.whatsapp.com/GEB1EPIAarsELfHWuI2k0H

Amazon Wishlist: amazon.com/hz/wishlist/ls/Y72CSP86S24W?ref_=wl_sharel

Well said, Nahum. Whenever I see Shadal challenged, I have to remind myself that I don't necessarily agree with everything he ever said, and yet I feel called upon to at least give the answer that he might have given. So here goes. I'll expand on Nahum's quote from Shadal on דברים ו:ה by citing Shadal's letter to his friend Giuseppe Almeda (excerpted from my translation at https://hakirah.org/Vol%2010%20Klein.pdf):

"True Religion is not the science of divine matters (a science that is too far above the reach of man); it is an intimate belief, a filial devotion, that extends itself in... practices and observances that are determined by law. The goal of such law is not that God may become known and worshipped by us, as if He were in need of our homage, but rather: (1) to keep alive in our minds the idea of God and of Providence, the only idea that is capable of keeping us constantly attached to virtue; and (2) to accustom us to keep a rein on our desires and to undergo privations patiently, an indispensable attitude for rendering us superior to the passions and the temptations of vice.... Jeremiah reposes the glory of humankind in the sound knowledge of God, that is, he says, in the knowledge that God is that Being Whose acts are universal compassion, benevolence, and justice; for these, concludes the prophet—introducing God Himself as the speaker—'these are the things that I desire (that people should do)' (Jer. 9:23).... that is, the knowledge of God is not desired for its own sake; compassion, humanity, and justice are what He desires; it is important to know Him so as to practice the virtues that He loves; 'these are the things that I desire,' says God, not a sterile knowledge of Me."

Note that Shadal, to support his point, is citing the very same pasuk in Jeremiah that Rambam cites in Hilchos Yesodei ha-Torah 1:1 and Moreh 3:54!

As for your question, what does Shadal hold is the value of learning (or engaging in) Torah lishmah?-- I have no direct quote from Shadal on hand, but the best way to understand "Torah lishmah" might be to understand its opposite, "she-lo lishmah." According to Mesillat Yesharim ch. 16 (by the "other" Luzzatto), this means engaging in Torah not "for the sake of divine service,

but rather in order to deceive others and to gain money or honor." In other words, engaging in "Torah lishmah" need not be understood only as a pure intellectual exercise or a search for "truth," but as means of serving Hashem. I thinks Shadal would have endorsed that idea.

Great article as usual! There's no question that your approach has strong support from Rambam and other Rishonim, but I think the more interesting and important battleground will be the views of Chazal. Those Rishonim who did push back against Rambam's intellectualized summum bonum highlighted the fact that nowhere do Chazal present a legal obligation of belief. Shadal is on firm ground when he writes in his "Letter to Almeda" that Judaism does not command belief, because it does not attempt to command that which cannot be commanded.

As far as I can tell, Philo of Alexandria is a much more likely source for Rambam's view. After articulating what has been called ""the first creed in history," his emphasis on religious dogma became the direct inheritance of the Church, from which it spread to Muslim theology and then back to his native Judaism. But even Philo presented his focus on beliefs as a means to an end; not the essence of human perfection. On the contrary, retaining a certain ambiguity or skepticism regarding the big questions may actually allow us to live in greater harmony with ourselves, our societies, and even our Creator.